Friday, February 21, 2014

“ Stricking Oil “ exhibit by Michael Lewis reviewed by Debora Alanna

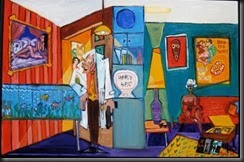

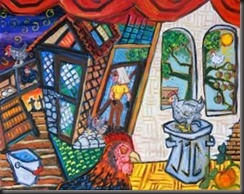

Sea Czar City

Vegas, In The Desert Of My Mind

Michael Lewis - Homage

Michael Lewis – Striking Oil review by Philip Willey

Michael Lewis – Times Colonist by Robert Amos

“My images are not products of the spiritual realm, they are comics with no continuity, anti-animated post salon nostalgic slapstick. It was the discovery of George Grosz and William Gropper that taught me that rage can look like a political cartoon on, delight can dress itself up like Batman – that you don’t need a diamond drill bit to strike oil, sometimes a paintbrush and pencil will do just fine.”

~ from Michael Lewis’ artist statement .

Walking around Dales Gallery where Michael Lewis’ Striking Oil hangs (until February 26th), I imagined hearing Henry Mancini’s orchestra playing Stardust merging into a melliferous medley, then, gunning with sharp and sassy sax and bossa rhythms. Perhaps, Orsen Wells’ guttural tones rasping Mike Hammer’s voice overlaid with scratchy radio waves. I heard the rat-ta-tatting of weapons and cat-call whistle blowing pronouncing danger and decadence through affable memories, as detective fiction will engender mystery and mayhem. Utilizing his strong connection to the 50s movie, TV and pulp fiction genres, Michael Lewis’ work is sharp-witted and vociferous, oil works of striking saliency.

Conspicuously pure colour vaults and jostles the viewer. Hard edged characterization snatches, grips where grappling of imposing political stances are decried, and underdogs as comic book immortals reign. Coy and suave characters are juxtaposed, painted to reverberate cartoon sensibilities with current concerns that still twist us.

There is much more here than what aficionado honours present. Experienced colours and shapes Lewis’ grasp and engagement of Victoria’s disadvantaged for decades where he worked to ameliorate their strife. In Lewis’ work there is no ploy for brazen hero worship. Through his treatment of what influences him he explicates social mores currently frightful today, which is more distressing than invented plots, whodunit narratives. Lewis’ exploratory shading, askew delineations, architectural cartooning, parquet grounds and ceilings and walls et al, illustrates his incisive tenderness through comicalness, and catchy visualization.

He darkly outlines urbanity’s folly. He drills at our dismissals, and self-conscious clumsiness with firm unadulterated colour and misproportioned extremes, demanding outlines addressing our disproportioned views of the world’s woes, our imbalance as a result of political choices and commerce’s greed – war, warring spirits, the aftermath of battles, pecuniary strife. Painted wisecracking amplifications of heartfelt pronouncements as visual puns keep us from tearful, presumptuous conclusions. Scruffy wastrels, goofy animals are symbolically and often satirically recalcitrant, headstrong and stubbornly resistant to off-handed speculation and in defiance of societal condemnation. Lewis’ madcap treatment of affectionate recollections, his jovial figures and evocative scenarios play with our complacency and pop us on the head.

His paintings are mostly a juggling of angular compositions with varied lens shot or storyboard views, perhaps digesting Ben Shahn compositional ranges - wide angles or close up stills, overlays saturated with bold, quirky objectivity. Lewis’ shrewd and mindful work allows a cheerfulness to help us through the compelling and significant aftermath of his formative and collective post World War 11 experiences, societal bargaining of the War damage and consternation, and inescapable, painful observations of people imposing as William Gropper figuration, experiencing poverty in Victoria BC.

During the twenties of century through to 1933 when the Nazis came to power, an 1924 exhibition held at the Kunsthalle in Mannheim curated by Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, the Director showed artists that rejected personal romanticism of the expressionists, and wanted to characterize public attitudes. They further defined themselves and their work utilizing the title of the show, the New Objectivity (in German, Neue Sachlichkeit). Although these artists generally were concerned with a characterizing of events, there were two distinct ways artists worked within the New Objectivity movement. Classisists, or the right wing artists aimed to ‘search more for the object of timeless ability to embody the external laws of existence in the artistic sphere’. George Grosz and Otto Dix were two of the the verists, or left wing artists who allowed ‘tear the objective form of the world of contemporary facts and represent current experience in its tempo and fevered temperature.’ [1] [‘Sachlichkeit should be understood by its root, Sach, meaning "thing", "fact", "subject", or "object." Sachlich could be best understood as "factual", "matter-of-fact", "impartial", "practical", or "precise"; Sachlichkeit is the noun 'form of the adjective/adverb and usually implies "matter-of-factness.’] [2]

Lewis’s work incarnate, lively characterizations shows his chronicling constancy faithful to the matter-of-factness inundating social constructs, anthropomorphizing the animal in us, humanizing the superstar features at the heart of relational entanglements. Lewis records the jagged and the out of kilter in humanity’s interactions, foibles with precision and a blaring palate, because humankind is so palpably wonky and colourful.

Referring to his personal concerns, Lewis collects, recollects and bares his memories, divulging stilled sequences of a life lived through the exhilaration of fact as fiction presented through his mind’s eye. More, he is a painter of folks, ordinary people seen through his extraordinary vision. He redeems their inadequacy with his brave and assertive brush. Confabulation becomes actualized as historically

important interpretations. Lewis chronicles lives lived through the vehicles of social realism, comic rendering and quick witted panache of mediated media. His works are precise and expository, blatant astuteness made with a chuckle so we too can enjoy societies foibles, its waywardness while thinking of the overall import Lewis brings us to, to ponder in our naiveté .

Lewis’ works deliver unexpected causality, reframing and reinterpreting, demonstrating how we can grasp, live with the bewildering, confounding any assumptions. Fraught with the sensationally humourous and charming sequences intensified scenarios, double meanings, visual syllepsis or paraprosdokian approaches and schemes illustrated, Lewis ensures we focus on his perspectives, uncompromising blatancy with jest cosseting the dark side charitably.

An interview with Michael Lewis by Debora Alanna held 2 February 2014 at Dales Gallery during his “Striking Oil” exhibition, with quotes by the artist that accompanied his paintings and subsequent thoughts about Lewis’ work by Debora Alanna.

M = Michael Lewis

D = Debora Alanna

Kiss Me Deadly - 36 x 24" by Michael Lewis

“I got my first breath of cool from television detective shows. I wanted a girlfriend like Honey West, a woman with her own ocelot. I wanted to hang out at Pepe’s with T.H.E. Cat. I wanted to play pool with Peter Gunn and piano with Johnny Staccato. I wanted to listen all day to Mr. Lucky jazz. I wanted it to follow me down the street like a sound track. What a crazy kid’s wish. I had no idea it was yet to come.”

~ Michael Lewis.

D Journeys through Michael’s world.

M One of my fetishes is 50s detective novels. Movies. Television shows.

Kiss me deadly is done off a poster from a movie called ‘Kiss Me Deadly’, a Mike Hammerfilm An anti-Mike Hammer film.

D Anti?

M The director took the character, who in the 50s was very popular and made him into a fascist idiot. In the film he was treated as a fascist character. At that time, Mickey Spillane was the bestselling novelist in the world The director felt there were such levels of fascism in it that he took his book and twisted it to his own design and made this classic film

Honey West was, in the 50s was a television female detective. And this (central figure) is my version of Shell Scott, who was a lampoon of Mike Hammer. There is a fish tank in a description of Mike Hammer’s apartment. The cat album is Mr Lucky,. Henry Manccini. The other album (in the painting) is a version of Richard Diamond. This TV detective shows became my introduction to jazz. Peter Gunn. TV detective jazz was my first exposure to jazz.

D What’s happening here? You have a central core. You have abstraction. The mask.

M I wanted to do a version of that 50s hip decor that often had African masks.

D And the orange couch.

Lewis has adopted some of the objective styling and rational commentary, outlining actuality seen in the New Objectivists verists. However, Lewis brings lightening palaver of high spirits into his work. He combines sharp, humourous adoption of mid century comics together with a witty demonstration of the inscrutability of TV menace and jeopardy, exercising persuasively slick film generalities and the spectacular and unfussy verity of pulp literature, staggeringly. Lewis allows the intensely impassioned but simplified ideas to supersede human impairment, demarcating an emotional maturing through an expressionist treatment of his affecting influences. Kiss me Deadly expounds the mid century genre with distinguishing form, style and subject matter. The shape of the TV, the period lamp(s), the flat top haircut, the turntable spinning an ambiance of heavy mid century colours. Green shadows and fixated women decorate. The large fish tank occupies nearly half of the centre of the picture plane – a think-tank of discordant gaping fishes bubbling their air, reflecting the TV bubble shape, and the mouth of the ‘Kiss me Deadly’ poster. Lewis paints a foreshadowing or embrace of irreconcilable smacking, critical remarking, a gibe about the lethal and implacable world of mortal’s glancing blows.

Sands - 36 x 24" by Michael Lewis

“I grew up in Las Vegas. I met both Red Skelton and Vincent Price when I was a teenager. I tried to sell them a painting. It wasn’t one of mine. It was by an artist, like them now, long since gone.”

~ Michael Lewis

D The Sands, as in the Sands hotel?

M Yes. Because I was raised in Las Vegas.

My mother was an antique dealer. She had this painting. We had two appraisals. One was that it was authentic. The other was, that it wasn’t. It was a copy.

D Either or.

M Ya. It was by an artist named Gottfried Mind. He had some form of autism, some form of socially unacceptable behaviour. He came from a British aristocratic family. They gave him pencils and paints. He turned out to be a quite proficient painter of animals. My mother had a painting on porcelain that was supposedly by him called “The Cat and the Kittens”. And if it was by him, if we could actually authenticate it, it would have been very valuable. We didn’t have any money at the time...

She had made contact with both Red Skelton and Vincent Price, who were both art collectors. But then she became too ill to attend these meetings so, her star struck, very inept son went to meet both of them to try and sell this painting.

D You?

M Ya.

Skelton was playing at the Sands at the time. He was also having his first art show. He started painting clowns. They had a bungalow in the back for him I had an appointment, a day to go meet him. When I went out he was more or less like this... He was in the swimming pool, in a sou'wester hat, painting on a little floaty thing. That is how he kept his weight down. He was in the water in this coat and hat sweating like crazy. Just sweating massively.

Vincent Price I met at a book fair. He was a gourmet cook, and he was flogging his cookbook at that point and doing cooking demonstrations. That’s why I painted him with a meat cleaver.

We had two different appraisals, and they said unless we could get an appraisal that it was verifiably authentic they weren’t really interested in buying.

D Whatever happened to your mother’s Mind painting?

M It went to my uncle, and then I believe my uncle said it went to the San Diego museum.

D I love the car, with fins one cannot easily maneuver around. I love how the golf flag is like a musical note.

Would you explain your asymmetric exploits in your paintings?

M There is a lot of influence from German Expressionism. I mostly have 3 influences – the American Social Realists of the 30s, the German Expressionists of the 20s-30s, and the Sunday Funnies.

Sands presides over a real fabricated memory, managing the lighthearted and anomalous lives and funny people that two entertainers animate. Meetings between Red Skelton and Vincent Price are combined into a single work. Yellowy sky, rails and roofs askew, the desert sands bite into the grassy golf plain as the stars star in bizarre antics. Lewis’ work challenges the eccentric madness that celebrity creates. The work demonstrates the grains of lunacy, the idiocy of being full of polish with the artificial boundary between the ordinary public and stars. He implies that crossing the line between them and us, or the sandy frontier between sanity and sensational behaviour is troubling as his cockeyed landscape and crooked portrayal of these performers’ realities. Ignoring or hiding from obvious signs of danger, salacious folly buries its head in the sand.

Politicians and Pirates - 52 x 31” by Michael Lewis

“Battle in Seattle and then some.”

~ Michael Lewis

M This came out of the Seattle confrontation and riots in 1999, where there were protests around the World Trade Conference that became known as the ‘Battle of Seattle’.

D Your Gap store looks like no Gap I have ever seen.

M That’s part of the whole corporate deliberation.

D It’s using ‘gap’ as the other meaning of the word.

M I’ve always loved that. I don’t understand. Do they do this on purpose? If you look at the Gap, manikins don’t have any heads. Like there’s no brain. There is a hat and a shirt, and nothing in-between. I don’t understand that as an advertising device. You have no brain if you come in here and buy these clothes. That’s what it is saying to me. I have always wondered who came up with this and why.

D You have a cross of light in the apartment windows. You have the world dissected vertically. The Seattle light is all grey.

The police shop at the Gap?

M Ya, they are all faceless. They do look faceless. That’s part of the intimidation.

D Who is the pirate?

M Robber barons. Corporate entities.

D If only they looked as dapper.

You painted a lovely green door, an escape route? Then you have three windows, each with a different window treatment. And they are askew. They are almost the face of the building. You know how windows become eyes of faces? Then there is a lit window on the far right, an empty window.

M They are all pretty well empty.

Delving into the gap between inconsolable breach and unnerving alliance between politics, police states, pirating, Politicians and Pirates gapes and ransacks these realities, presenting the official to the pirate with a firm handshake bathed in the light of a staged play. Undisclosed police rail, ready to attack. The Gap store, featuring a featureless manikin is explicit as a phoneme where a business model of humanity is slight and slighting. The red orange moon in à la El Greco sky, irascible, Lewis brings worldly mayhem to balance on a tippy roof of the public eye(s), with a dark stairway to lighting up divinity’s horror is not candy-coated, although he uses candy colours. Lewis does not minimize the unpleasantness, the difficult actions that occurred in the 1999 Seattle riot, but offers us a confectionery insurgence to think about what is unthinkable.

If We'd Help Each Other - 24 x 30" by Michael Lewis

“The men who were my father figures when I was a kid, were men who had ridden the rails during the depression and tanks during the war. If Dagwood had been a real man, he would have been them He would have come home. He would have tried to act normal. He would have married Blondie. He would have known she was smarter. He would have always felt awkward around her. He would have taken a job he could never get to on time. He would have erupted into violent fights with the postman for no reason at all. He would have had kids he would never understand. He would have tried to hid in naps on the couch. He would have been awake every night. He would have sat in the kitchen making impossible sandwiches. I would have seen him on Sundays and laughed.”

~ Michael Lewis

D If we’d help each other with the work around our houses it would make it look a lot easier?

Look a lot easier. If we help each other.

Would you tell me about this?

M This is a series of Dagwood paintings that I did. I was really fascinated by men that came out of the Second World War. They had gone through the Depression, gone through the War. Growing up with the Sunday Funnies, Dagwood is the prototypical duffus, male goof. If you look at the paper, he might have been a real person that had gone through the Depression and the War. It started with him as a young man in his 20s, as a young college student. Though, I began to look at the comic strip that often had these – he would erupt into violent fights with the postman over nothing, often images of violence that seemed to erupt from nowhere. He would be sleeping. He was always trying to take a nap, sleep in the afternoon, get away from things.

He had several dogs. He had Daisy, and all the other pups. He had the wife and family, the whole suburban thing. And yet he is up at night making sandwiches. He obviously can’t sleep. I started seeing him as this funny figure. But if he had been real – I started seeing this whole trauma of his life. I did a series of about 5 paintings each, covering a different aspect. This was the first one.

D Would he have ever had a portrait of this woman in a bathing suit like that?

M This is Blondie, his wife. What I did is that I tried to take the image from the Second World War, the famous pinup of Betty Grable. I did the Betty Grable and put Blondie’s face on it.

This (officer) is like MacArthur, but I used Dithers, Dagwood’s boss for the face. Herb Willy, Dagwood’s friend, and he... I used an image from Life magazine of two soldiers, and I put their faces on the soldiers. The panels, words, I lifted from a Dagwood comic. If we help each other... was this friendship, and what the friendship had gone through.

D You’ve painted the post War ‘ticky tacky’ houses.

M That was what was suburban.

Dagwood Bumstead and Herb Woodley, main male vehicles for Chic Young’s ‘Blondie’ comic strip have a conversation, where Dagwood explains how helping each other makes chores look easier, in a speech bubble atop If We’d Help Each Other. The two men walk in ordinary suits, but the shadowy soldiers they were hunker into battle. Dagwood’s boss, Julius Caesar Dithers wading in insubstantiality postures in a false memory as General Douglas MacArthur, looking over the war year the men experienced, traipsing towards their current reality. Blondie (née Boopadoop) as a buxom pin-up girl, maybe hearkening to her flapper girl past has a crooked shadow. Haunting and eerily grey in her existence as Dagwood’s help mate, Lewis paints her looking at us, challenging us to accept that she is not just a housewife. Lewis’s parades the strife of a post war subsistence, where there is frail differentiation between what was and what is in a veteran’s life.

Late for the Train – 24 x 36” by Michael Lewis

“Part of a series of apologies to the men I grew up around when I was a kid. Men who tried to lead normal lives after coming home from the war.”

~ Michael Lewis

M This is treating the Depression. It’s called Late for the Train because Dagwood is always running for the train, always late. I thought, during the Depression, he would have been running for box cars.

D That’s a symbol on the door. What is it?

M That’s (Al) Cap and (George/Ham) Fisher. I wanted a couple of other cartoon characters that looked like they were hobos, so I used Humphrey from Joe Pallooka.

D On top of the box car?

M Ya. That was done by Fisher. One was Lil’ Abner that was done by Al Cap. There is a story between those two because Al Cap had started as Fisher’s ghost artist, and then had created these hillbilly characters which he did a version of for Lil’ Abner, and Fisher said he stole his stuff. They had this huge fight that went on for years. There are some references here.

Another rumination about the post-war life, Late for the Train again features Dagwood and Herb on their commute to work. In the comic strip - Dagwood was invariably late for his train. The consistency of tardiness for work forced on him when his parents disowned him for marrying Blondie shows how being employed in J.C. Dithers Construction Company is uncomfortable, a destination unworthy of his punctuality. In the background, a cargo trail roof figures Depression era comic characters by Al Cap and Ham Fisher. An idyllic countryside rolls through the car door. Heavy dark clouds overcast, contrasts with the quick sandy space between the cartoon lives, the endurance of strife of each set a challenging ride in either each direction, past and present is latent with a kind of catching of a train of thought, where clarity is practically approximate, a rough and transitional scuttle and can never be quite fathomed.

3 A.M. - 30 x 30" by Michael Lewis

“There is a creature that comes into old men’s rooms when they sleep. It sits on their chests until they wake. Then it is gone.”

~ Michael Lewis

D Is that you at 3am?

M I think it’s a lot of people at 3 am.

D It is a very urban scene behind there. Urban and yet not, because of the fence. So, suburban?

M I tend to use iconography from Expressionism, The way the city is described.

D The skeleton image on the blanket?

M It could be a foot on his chest. It’s that thing that wakes you up at 3 in the morning. Heavy.

D Pressing on your chest.

M Ya. It is a lot about age. And anxiety. I wanted something for that pressure on the chest. That became this sort of figure.

D What about the horse?

M That’s a Greek figurine. I have always had it in my room, and have always liked it. It was a little tourist piece that someone sent me. I wanted something there that was unusual. It is also nightmare (night mare).

D The double entendre with that. That’s what is says right there, ‘night webs’.

M Night webs.

Languishing within time’s imposition, miserable howling of a dog skeleton is stark at a wavering fence. Early morning, untimely sharp features are too close to closure, to the wake of finality. The import of disheartening sleeplessness is at variance with a naked woman in a semi-shaded window, a view to what was or what seems unattainable through aging. The alarm is alarming, a red hexagon, poised to ring at any moment, the hex, enchanting dream of sex. Shelved books uphold a Trojan Horse sculpture looking a little spent for subterfuge. An elongated skeletal footprint or fingering of the immensity of heartache presses within exceeding the covers. Bricking the left wall, Lewis paints the interior/exterior leanings of architecture under the eschewing influences of the hex of the moon. The brick wall chinks seems explicit and substantial, less a puzzle than the serrated city. Lewis acknowledges what undeniable and stolid in his existence in spite of the capricious presage of evocative imminence haunting the sleepless male, although the bricked pattern escapes in the split wall covering below the nude. Again, memorable yearnings as impetus prevail – 3 A. M. encapsulates an interval of awakening.

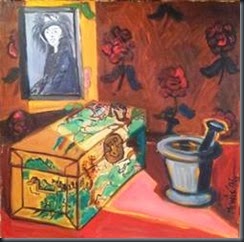

The Box - 24 x 24" by Michael Lewis

“What I have of my mother. I have a hand painted Chinese pigskin box. I have a mortar and pestle. I have a photo of the young her in the 1920s.”

~ Michael Lewis

M These are three objects I had from my mother.

D Is that her on the left?

M Yes. I had a photograph of her in the 20s, when she was in her 20s. She was born in the 1900s.

D What an amazing time to be born. She always lived in the USA?

M She spent some time in Australia. In my blog about growing up in Vegas (Vegas, In The Desert Of My Mind)... I was looking at old photographs. One I used was this great old photograph of when she was on the liner heading to Australia. They came up to Victoria, first. She took a picture of the Parliament buildings in 1931, maybe. That was really fun to see. It hasn’t changed that much, except for a car that you see parked in front that’s not from now.

D What about the floral pattern on the background?

M It is my memory of the house I grew up in.

D The box is Oriental.

M I had these three objects from her and some photgraphs – the box, the mortar and pestle and the photograph. She was very interested in Asia. That was her personal box where she kept her personal papers, that sort of thing. Meant a lot to her. It is a lovely box. I still have it.

D The mortar and pestle. How did she use it?

M It was for making medicine. We didn’t have any money so she used it for making home remedies.

Maternal vestiges are honoured amid the strength of ever blooming, transitive roses in Lewis’ The Box. The clout and urging, the weighty mortar and pestle compels as a stalwart routine. As a discerning confidence in enigma, a Lewis paints a sun lit box belonging to his mother. The private box is exclusive to Lewis, now. This article of poise is painting made throughout affectionate connectivity, and positions as a closed, with delightfully painted Oriental scenes on pigskin. Revealingly intrepid in flourishing feather finery on a sill as a jaunty portraiture, Lewis painted his mother as she appears in a photographic memento. A formidable tribute to his mother, Lewis intimates nobility within the capacity of the picture’s containment.

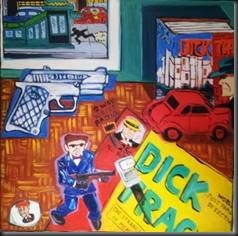

Dick Tracy - 24 x 24" by Michael Lewis

“Before big screen TV. Before 3D movies. Before music videos. Before comic books. There was the LA Times Sunday Funnies. It came in a section bigger than any could kid could hold. A perfect blanket to lay on and fall into.”

~ Michael Lewis

M The Sunday Funnies were my first and probably most major influence because that was the source of my colouring books. My mother would.. she had a pretty good eye. She would draw panels out of the Sunday Funnies and those would be my colouring books. She would draw and I would colour them in. I loved the Sunday Funny people. I couldn’t have comic books. For one, they were expensive. And it was during the 50s when it was when comic books were evil. It made children into juvenile delinquents. But I could read the Sunday Funnies. Funnies were just fine.

D Why were newspaper comics more legitimate?

M Because it was part of the newspaper, which was an adult medium

D Already sanctioned.

M Ya. Comics, what started that whole scare was Dr Werkman in his book, Seduction of the Innocent he wrote about the evil of comics referred to the horror comics made for people that had come out of the War. Those kinds of comics is what they carried into war with them. It was easy. The horrific quality of the stories was designed for adults, not particularly kids. But of course, kids could have access to them. That’s what horrified adults. Soon, that stain went over everything. Donald Duck was just as bad as decapitating people. You can find these as films on Youtube. Propaganda films. There’s one that’s really funny. Three little boys are reading a comic. Suddenly, one boy pulls out a pocket knife and starts jabbing it into a tree.

Churches had big book burnings. They said, kids bring all your comics and we will burn them in a big bonfire or they will turn you into a juvenile delinquent. So my mother said, no no. But I still had the Sunday Funnies.

D You have a binder of them in the painting?

M No that’s from the Big Little Books[3]. It is an image that shows up in my work, like the crooked tailed cat, the bent ash can, designs that seem to be recurring.

Dick Tracy plays with Chester Gould’s ‘Plainclothes Tracy’, and later, ‘Dick Tracy’ iconography, allowing toy sized artifacts of the detective’s story with impossible gadgetry (2-way watch radio), weapons laying about the decoratively patterned floor to quell evil doers that are escaping in a picture frame. A collection of ‘Big Book’ stories lies in wait for further reading, and ideas to thwart the rogues. Flattop Jones, villain with machine gun looks for trouble. A Jr. button behind him, Tracy Junior is as always disposed for and enthusiastic for the intrigue. The bold coloured drawing of a real sized pistol is placed to be at the ready. A child’s recollection of urban crime drama utilizing Tracy’s wits and science to foil the bad guys are Lewis’ comforting ploys to substantiate that all will be well in the end, even exciting in the conclusive thrall.

Mother and Child - 24 x 35" by Michael Lewis

“A better title might be Holy Land”

~ Michael Lewis

M It should probably be called Holy Land. The Mother and Child defines the work too much towards the Christian version. My idea was that symbolic of the Holy Land was Christians, Jews, Muslims – any denomination. It is what we call this place where all this horror happens – Holy Land. The land is not treated at all holy.

Mother and Child shows a feeding of humanity, nurturing of essential and fundamental needs in the wake of impending hostilities. The reclining male blends into the flooring, camouflaged and coiled into a fetal position. He is representative of how the complexity of war reduces mankind to unabashed neediness.

Gimme Shelter - 32 x 26" by Michael Lewis

“After thirty two years working with the homeless, some images just get stuck.”

~ Michael Lewis

M Years of working at Street Link.

D Police with the symbol for ‘Do Not Enter’ on their uniforms. You have a Hudson’s Bay blanket, very symbolic. This aperture is not straight.

M No. At Street Link, and probably it is there till this day, a fish eye lens was used to look out onto the street. You can get more of an image of what is outside with that kind of lens. It also made the entrance very claustrophobic.

D Weighty.

Gimme Shelter by the Rolling Stones:

“Oh, a storm is threat'ning

My very life today

If I don't get some shelter

Oh yeah, I'm gonna fade away”

Lewis’ Gimme Shelter is an aspect of his working life as a homeless shelter worker. The view is bowed, as the illicit bows humanity. Policing dominates and belittles scarred individuals. The Hudson’s Bay blanket enfolds as suffering’s wrap, the cost of commerce’s embrace. Headlights stream onto the forsaken road where shelter is problematic and prohibitive because it will not solve the problem of damaged souls loitering, lurking and lingering on the proverbial razor’s edge.

Femme Fatale - 32 x 26" by Michael Lewis

“Too much Tex Avery as a kid.”

~ Michael Lewis

D Here we have Femme Fatale. This is a little more jaunty.

M My comment was, too much Tex Avery. Growing up with 50s cartoons, particularly the sexual content of Tex Avery cartoons.

D That’s quite a car.

M That’s my shark car.

D Do they really exist?

M No. It is a take-off on the shark fins, that existed. I decided to paint a shark as a car.

D You have signage that says Femme Fatal. And you have a trapezoid, yellow, dominant and central.

M The window(s)? Artists’ mistakes.

D There are no such things as mistakes.

M Sure there are. There are all kinds of mistakes. I often don’t know what I am painting till I am finished. I have an idea. Then, oh ya, that’s what I am painting – when it is finished. I wonder, where did that come from? What does that mean? It is the internal dialogue.

Audacious and reliably slick, Femme Fatale (from the French, meaning fatal woman) is an archetype in myths and legends, a stock character throughout literature and eventually in clichéd popular illustrated comics. “Although typically villainous, if not morally ambiguous, and always associated with a sense of mystification and unease” [1] femmes fatales can be antiheros and redeem the story for the greater good. They are almost always mysterious and seductive, their temptress personas is one of their ways to hide their intentions. Lewis paints an exaggerated red clad female in wide stride with an equally elaborate pooch. A shark fin turquoise, larger-than-life lines of the finned vehicle is parked with a flat topped made leering at its side, in expectation of seduction. Signs separating the “Femme”, diagonal and positioned upward up, and “Fatale”, a pointed sign directing us down hold the viewer between what is enticing and what is dangerous. The painting is staged as in a movie set, the spry cut out city all melded into one resolute backdrop. In the middle of the picture plane, a trapezoidal window, blaring as is the unknown in any story line, demarks the wonder and possible desire of female wiles, craving. Yearning for what is unattainable can be an chancy interface. The out of kilter, smudged golden window, matching the other window’s light but larger and predominant, and fella’s golden hair, his brain wave of the dazzle of imagined consummation is Lewis’ assertion that ideals conceived with impossible female characters might not have an idealized golden result, and may indeed be fatal, although they may be fun to fantasise about in the light bright cartoon world.

Sun of a Beach - 24 x 36" by Michael Lewis

“The mermaid came out of a dream The richman came out of the sky.”

~ Michael Lewis

D A parquet beach.

M I had the mermaid image. It came out of a dream I started with that. There was the beach ball. Round images...

D Who is the fellow up in the sky?

M Attached to money? A big blow-hard. Hot air.

Ferris wheel and merry-go-round distant as memorable childhood experiences, a beach fire roaring – ‘where is everybody?’ a youngster might ask, a pile of money holding an inflated moneyed man, a star fish shape and a sandcastle all curve along the beach’s right edge inSun of a Beach, remnants of playful abandon, once upon a time. In the centre of the painting, a nearly naked woman stands beside the gold pile, underneath the floating business man. In the forefront, a gender unspecified gilled mer creature with fake breasts, with enlarged hands holds its tail, a fish out of water, stranded, fiery hair shot into the air. The sky drapes like drapes, the sun ogles the scene. We have to ask if the balloon man, inflated with his own power chose the cost of the nearly clad woman with the white bow and then metamorphosis took place and he transformed into mer creature, the son of the beach? Only Lewis knows for sure. This work personifies fervour of and dismay at overpowering persuasion scorching like a summer sear, with comeuppance hoisted, having a ball.

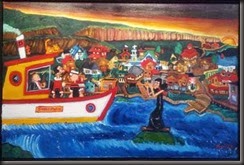

Sweethaven - 36 x 24" by Michael Lewis

“Final harbour. The ferry boatman will gladly accept payment on Tuesday for a hamburger today.”

~ Michael Lewis

M With a lot of my paintings, people say they are bright and happy. I say, well, here’s where it comes from They say, oh. This is my meditation on death.

D I got that. Because Popeye is not looking at you. You have a cross centrally. The sweet beyond Cliffs of Dover, or somewhere. And you had to have Wimpy as the pilot.

M He’s my boatman on the river of Styx. It is what I am hoping for. That the transition is nice and cosy. A haven.

D You have your fellow compatriots with you. Who is the woman on the rock?

M That’s the sea witch. She is usually the villain in the old Popeye comic strip.

D She looks like Olive Oyl’s mother.

M (Elzie Crisler) Segar played with those archetypes. She’s like the Siren, only in Classical mythology, she is a beautiful woman singing, draws you in. This is the ugly woman who’s flute playing will drive you onto the rocks.

D I guess that’s why Popeye is not really listening. What’s that creature on top of the boat?

M The Jeep. Eugene the Jeep. That’s where we get the name of the military vehicle. They named it after him. Segar brought two words into the English language. Jeep and goon. Alice the goon was one of the sea hags. Hench person. Until she got tamed by Popeye, and then she became Sweet Pea’s babysitter. Both those terms were invented by hiM The reason the word was invented is because that is the sound it would make. It would go, ‘Jeep Jeep’. It could prognosticate the future.

D He is whispering to somebody, but who knows who’s listening.

Sweet Haven, the boat chugs and splits the water avoiding the deep blue depths’ perilous rock where a sea hag and her lanky pillar touting the dire dirge she blows, a sleazy breeze. Elzie Crisler Segar’s characters occupy the boat. Jeep jeeps, Wimpy at the helm, Olive Oyl forward looking, Popeye’s turned away toward the cuddle of homes on the bank.of Sweethaven, maybe a sailor with more preoccupations tha destination, perhaps thinking about the inroads yet to navigate. Sunset colours, the day subsiding, the end of the journey is approaching. Lewis paints how the end of life can be a passage with allies, with friends, with caring people about you to accompany you while you traverse the unknown waters. No matter how quirky or anomalous or funny, ones’ relationships carry one through to Sweethaven. Lewis’ work shows his journey to be a salute to affection, a cosy familiarity. The indefinite finality is distant and glowing, green pastoral edging the dusk, the expanse met through a quaint, alluring multifarious village - a sweet haven, the ultimate refuge.

Fuck Off - 18 x 24" by Michael Lewis

“One day downtown, two ships passed in the light.”

~ Michael Lewis

Father and Son - 18 x 24" by Michael Lewis

“Granny has on her basketball shoes. Sonny is in a suit. Mom bought a dress she thinks makes her look nineteen. She saw it modeled by a twelve year old. Dad looks like a paperboy with tattoos. His progeny wears the camouflage of a soldier, knee deep in blood and mud.”

~ Michael Lewis

M Both these images (Fuck Off, Father and Son) I saw in Victoria on the same day.

D This guy’s pants on backwards. His whole body is backwards. It is very revealing. He is turning himself around for his son who is dressed as a preppy. It is a reversed image of what we think children and adults dress and behave.

M I saw this father what I consider kids’ clothes and his son dressed in adults’ clothes. I have seen that image a few times.

D What does that mean about our society?

M It is interesting. Both images were interesting for me because they are about how much the society has changed since I was a kid. When I was a kid there were very defined rolls. The adult would look like an adult. The child would look like a child. Now, you can switch them.

In Fuck Off – when I saw the woman, her butt was not quiet that revealed as seen in the painting. Growing up, a young woman would not be walking around with her pants slit open, and would not have those kinds of words on her shirt.

D You have painted the lollipop’s colours to reflect the woman’s red and orange shoes, and his glasses reflect the lollipop. A spin.

M To me, it is about freedom. She can dress however she wants.

There used to be Norman Rockwell kind of paintings with a good looking woman walking down the street and the guy or guys whistling. She never looked that intimidated. That was a male perspective. The women often were, of course. Now that whole thing has changed. Now, he’s intimidated. Am I supposed to look? Am I not supposed to look? She says, I will do whatever I want. That’s a huge change in the society. That’s a huge freedom that women have that they didn’t have. They were forced into a certain role.

D Also, the work is explicit. His lollipop licking looks like a masturbatory act. People kept that secret. That wasn’t talked about. Or, not in public.

M Again, he is not the aggressive predatory male that he would have been because she is no longer a submissive woman.

D There is no access at all. You have her shoes bent in a high heel look on one, and flat and accommodating on the other.

M That’s just supposed to be bent. You keep seeing things.

D There is a lot to see.

In Lewis’ Fuck Off, matching shoe colours, two strangers diagonally cut by a grey lot, their lots transect, ever so briefly. A youngish woman with a sprightly orange doo, the balding middle aged male and prominent brows share the same hair colour too. She turns to him, her orange glasses swirl in their frames. He glances back at her, his rippling candy twirls on his tongue. Her shirt bears the name of the painting. She wears the shirt as a sign, as an imperative, an angry dismissal for those that may take advantage of her. She will not be a victim. Yet she wears provocative jeans with a tear exposing her buttocks. He holds his lollipop as his sexual member, sucking on the confection with unease and diffidence while sneaking a peak at the woman passing. She gestures, challenging. He walks hand down, without a doubt that she asserts and he ascertains his distance, and he will never fuck off in his imaginings. He is the victim of her assertion. She is the victim of his insular behaviour. Their orange shoes barely meet on common ground.

The background city is lightly, densely painted, and we can expect that it is full of these trepidations staged for our viewing. Lewis documents cryptic innuendos within our society.

Father and Son shows a work is about the incongruity of perception, both in the context of familial interaction and societal prejudice. The figures stand in a light blue wash, a window barely visible, an elevated escape from preconceptions seems unlikely. The figures stand on a blue triangle close to the wall. They are pressed into, confined by the angling for each other’s understanding, both confused about the other. Equilateral, the triangulation positions the young and mature in a close proximity, equal in importance, and similarly odd. The kid, hair spiked looks astonished and appears single minded because of his glasses. He is dressed as an adult might in a white shirt and tie, formal slacks. His dad is clothed in street savvy garb of a younger generation, and is facing the wall, although his head swivels to confront his progeny, with a perturbed countenance.

Lewis paints a generational conundrum. Understanding is absent when bias prevails. Adopting what one thinks is appropriate makes wrong assumptions, and prohibits communication. Superficiality, assumptions corners both people in Lewis’ work. Clothes do not make the man, or the child. Lewis explicates that it is okay to redress audacious behaviour.

Robin Hood of the West - 25 x 32" by Michael Lewis

“My mother worked in a Western theme park. She took me with her when I was too young for school. I would sit at the knees of Doby Doc. He owned all the Western artifacts displayed in the park. He would sit in his rocking chair beneath his portrait and tell tall tales to the tourists. I would ruffle the fur of the wolf at his feet. He would say, “Careful boy! That is a wild animal and not to be trusted.”

~ Michael Lewis

M A couple of years ago, I went online to look up Doby Doc. I found several stories about this “Robin Hood of the West”. I also found a photo of his portrait. There was no image of a wolf at his feet. There was just an untrustworthy looking dachshund.”

I was making this was when I was doing the blog about stories about growing up in Vegas.

D How old were you?

M Five, six, up till I was seven.

M Still in my memory it’s a wolf, but obviously never was. I remember the portrait distinctly, and when I saw the photo it is exactly like it was except with a little dog instead of a wolf.

A triple self portrait, Lewis has painted the business of a Western theme park. The Lone Ranger in a Stetson poses with Pocahontas in front of a Saloon. on one side of the central painting of Doby Doc as an armchair Western adherent in the wild blue yonder, with a Sweet Shop on the other, the store where Lewis’ mother worked.. Lewis was allowed to remain in the Western while she sold sweets. The aficionado, Mr Doc in the foreground has aged, and retains the image of the artist as a boy with a wolf that he was allowed to pet is in the lowest edge of the work. This is ostensibly a three staged rendering of the artist in various life stages. Robin Hood of the West steals the artists’ childhood memories and gives them back to the mature artist to preside over and reinvent, replete with his compassionate storytelling.

Lucy - 30 x 24" by Michael Lewis

“I never wanted chickens. It is my partner, Jennifer, who has the feathered thumbs. Yet now I grieve for the ones who fell under the shadow of an owl or the neighbour’s dog. I’m happy their coop is no longer a drunken shed; but an egg layer’s Taj Mahal.”

~ Michael Lewis

M That’s Lucy. The chicken’s named Lucy. She’s doing strong. She was on the nest box this morning when I left.

D Why have you painted crosses in the background?

M Lost a couple of chickens.

D It is a happy scene.

M Ya.

D Spirals in the sky. Parquet on the walls. Chickens animated. Most of them are just doing their thing. One is really animated.

M That’s Henny. She runs. She’s nervous. She is a nervous chicken. She tends to run.

D Chicken layers’ Taj Mahal. A palace.

Lewis began chicken farming reluctantly but is now charmed by chicken husbandry. Lucy is a cock-a-hoop fowl theatre where red drapes suspend skyward. Asymmetrical hutches dazzle with jewel hues, a jumble of colours and textures but the gems are the hens painted affectionately. Lewis paints day and night as a simultaneous merging of time. Swirly stars on one side of the work, the gentle day’s sunnyness on the other gracing an apple tree with a white hen favouring a branch. The central female chicken care giver wears sunny cheer as garb. Although a few of the brood has met their demise, which Lewis sadly notes, most of the free range cluckers roost anywhere but in their coops. There is love and respect for the chicken family, where individuality is celebrated. Lewis’ chaos is intense and cleverly stirs. Lucy flaps off the picture plane, a lovely, complex tizzy of fluster and resolve.

Dryads - 30 x 30" by Michael Lewis

“In the gardens, three young women sat on the grass under the shade. Their bicycles and roller blades laid about them. They could have been forest nymphs, except for their clothes.”

~ Michael Lewis

M In the gardens at UVic there were three women just under the trees. Bicycles, rollerblades. They looked like they could have stepped out of an old painting. Except they were clothed. They could have stepped out of some symbolist painting. Mythological beings. I took off their clothes.

D That tree is sumptuous. It also looks like a coffin. At that time, people in many cultures were buried upright. They were the markers in the road. That dryad is coming to life.

That looks like a pig headed dog. He’s got his bone. Crooked purple road. And zebra trees. What are the zebra trees about?

M Birch.

D They look more like zebras than birch. It makes me think...

M Zoo?

D Wildness.

Mythical wood nymphs, have been conjured by Lewis in his work, Dryads, more than Sylvia Plath [4] was able to do. They appeared in a park, one emerging from a central tree, one on a bicycle and one jogging on a crooked purple path, a picnic and a playful dog complete the scene. Let’s call him Cerberus, the dog that guards, here, light-heartedly, the underworld.

It doesn’t matter if the tree is oak (Greek drys=oak), or in other cultural imaginings, ash or apple etc., it is the tree of life depicted throughout mythic history, within many cultures as ‘the tree that extends between earth and heaven. It is the vital connection between the world of the gods and the human world. Oracles and judgments or other prophetic activities are performed at its base.’ [5] Lewis’ tree is a dappled mottled flush, the twilight, a darkened city. In the background, separated from the park by a white fence, a lighthouse sized lamp is erected between metropolis and recreational area, lighting the way back to citified, sophisticated certainty.

‘... It was agreed, that my endeavours should be directed to persons and characters supernatural, or at least romantic, yet so as to transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.’ [6]

The dryads are curvaceous, a trio of ample nudes, each endowed with a selection of hair colour (a blonde, black haired and a brunette), representative of illusory, instrumental female enchantments. Like Coleridge, Lewis paints his willing suspension of disbelief in the creatures that mourned for Narcissus, that tried to prevent Erysichthon’s violation (cutting down) of their tree. He has resurrected their novel mettles, strong life-forces occupied with urban leisure in the park. Lewis’ Dryads is a celebration of all-encompassing harmony and excellence, telling virtue. His Dryads show femininity to be plucky and sincere in all their variations of natural splendour.

Definitely Not the Ripper – 36 x 48" by Michael Lewis

“A few years ago an article appeared in Vanity Fair. It proposed the theory that Walter Sickert, an English artist may have been Jack the Ripper. One day I went to an art gallery to see a painting by Sickert. The gallery director was being interviewed by the media. The director was asked about the Sickert/Ripper possibility. The director got very red in the face and shouted: ‘Definitely Not The Ripper!’”

~ Michael Lewis.

D As in Jack the Ripper?

M Yep.

D Why definitely not?

M Because that’s my version of the Walter Sickert painting. A few years ago there is was a theory that he was Jack the Ripper. When that article had come out, I was at a gallery. The gallery director was being interviewed by the media. They got to the Sickert painting and the media person said, so what do you think about this theory, that Walter Sickert was Jack the Ripper? The director got vivid red and said, get out! He’s definitely not the ripper. He got really upset. So I loved that – definitely not the ripper. I went home and painted Sickert. I painted the Ripper in there.

D The woman in the painting is who?

M She’s the media. The interviewer.

D There is an ominous shadow behind the people.

M Again, this is my version of the Sickert painting.

D The over coated male is quite large, square. The overpowering of the mystique.

Definitely Not the Ripper gives credence to the painter Walter Sickert’s story that he was definitely not (Jack) the Ripper. Known for painting musical halls and poverty stricken women, Lewis’ work includes a version of Sickert’s ‘The New Bedford (1915/16)’ in the background. Sickert painted music halls because they were a construct, a microcosm of his time period, epitomizing society. Lewis too paints societal constructs, the challenges imposed upon people by society. Lewis’ respect for Sickert is woven with the never ending yarn regarding the accusation of his involvement in homicide(s).

In the foreground, we have an enlarged, enigmatic male figure, seemingly of that artist, mysteriously clad in the period’s plaid overcoat and top hat, his back to us as a query that a female journalist in 20th century might have asked him, and plagued him in his lifetime – the possibility that he was Jack the Ripper. The story was based on his paintings, one that came to be known as ‘The Camden Town Murder’, one of a group of four paintings by he painted in 1908 titled by Sickert as, ‘What Shall We Do for the Rent’ or ‘What Shall We Do to Pay the Rent’.[7] Although Sickert enjoyed performance, had worked as an actor, dressed up in costume acting as different characters, as a painter he was adamant that he was not responsible for Emily Dimmock’s murder in 1907, nor any other murder of women. Lewis’ portrait shows Sickert dressed as the Ripper, asking us for the benefit of our doubt, not to assume his guilt.

In his defense, Sickert explained he could not sever subject and from the way he painted his subjects:

“Is it not possible that this antithesis is meaningless, and that the two things are one, and that an idea does not exist apart from its exact expression? ... The real subject of a picture or a drawing ... and all the world of pathos, of poetry, of sentiment that it succeeds in conveying, is conveyed by means of the plastic facts expressed ... If the subject of a picture could be stated in words there had been no need to paint it.” [8]

Lewis’ work safeguards Sickert, both as a revered painter and shielding him of the accusation that he was a murderer because he painted nudes with clothed males present in the paintings. Offering us the public drama of grave accusations of serious scope, Lewis paints the accuser as a forthright red head, in contemporary outfit, with microphone, her backside thrusting out, questioning her capability to be balanced. Her shirt cut down her back, black skirt slit up reveals that sexiness matters when it comes to influencing the public belief of the truth. Apparently there is still a question today that lingers, and within Lewis’ earshot (see interview above). Sickert, in Lewis’ work is larger than life, sinister, but because he has chosen to paint Skickert’s back only, we see Lewis offers us the adage, not guilty until proven – we cannot see, as Lewis does not allow us to see that there is a face to a crime. If there is no face, how do we know whodunit. In the spirit of Lewis’ crime fiction influences, we can assume nothing. And Lewis gives us all the intrigue and mystery inherent in the narrative, generating a thriller. He imparts his indefatigable capacity to marry the social realism of today’s attitudes with the murder mystery genre.

On the Rocks - 30 x 30" by Michael Lewis

“One day a body washed up in the harbour. At the time I knew his name. I have forgotten it by now.”

~ Michael Lewis

M On the Rocks.

D It’s a very lonely looking piece. A white tug boat echoes the man’s white t-shirt. You painted the tugging of distress, the wrenching of anguish.

A large middle aged male corpse lies prone, exposed on a projecting mass of sharp boulders. Lewis paints a man who may have had to choose or had no choice between sickening and intolerable alternatives – addiction and or illness, poverty and death. Adversity is largely featured in On the Rocks. Misfortune, hardship, danger of needs not met are bared as an austere and inhospitable demise. The harbour is distant, but visible. The body’s place of origin is unclear, but Lewis paints industry and its effluence prominently. A mention of religious thought lies in the cityscape’s turbulent skyline. Near the city, he paints pillars that haphazardly consort with no dock or harbour access.

Lewis shows a man that was strewn far by the tides by self destruction tendencies and or societal rejection and neglect with no information to ascertain his origins or identity. What is clear is Lewis’ pathos. His account of suffering confounds social theories, painting the reality of wanting. Lewis surpasses his predecessors Gropper or Grosz with his profundity emerging from his years of experience with others’ depths of despair appearing as a testament to misery. Lewis is not preachy or imbued with the incongruent social mores and narrowing politics. Leiws’ work is sober and illustrates the arcane, reveals heart wrenching inexorableness. The man is painted large and is unavoidable because this solitary event is a quandary of instability we all share, is present and is unavoidable.

Lewis gives us a bit of reprieve from tears by incorporating a comic book styling to his imagery. Maybe this guy was really a comic book villain? Maybe Tracy or Mr Lucky will save the day? If only.

Beach Open - 20 x 16" by Michael Lewis

“The day your buddy’s older sister becomes more interesting than he.”

~ Michael Lewis

D Becomes more interesting than he. Parquet beach. This towel design is a very period design – the zigzag. It was used in design beginning in the 1930s (produced through to 1955) Gerrit Thomas Rietveld’s Zig-Zag chair, the impossible construction that defied physics, and later the Missoni family fabric/ fashion design, with others’ designs for the past 6o years worn to defy the norm.

You get the feeling the diver is diving shallow, that there is danger with the dive. Floating logs curve, forming a separation between the idling person on the floatation device and the broken line formation creates a swimming lane. The boys are much smaller than the girls, who seem much more grown up. The girls pose for a photo. The towel becomes a mirror image of the dock – another kind of platform – a runway. Your crooked tail cat is about to plunge, tempting fate.

Youth, the memory of it, the summery solace and beckoning enchantments of sexual awakening possesses us in Lewis’ Beach Open. The work refreshes us with watery splendor. Beach side antics in the forefront of the delicious scouring of blue water beckons as the cross hatching of the beach holds us captive. Laps as recollections of effortless foreplay, the inner tube of repose after the facts of life are experienced are smooth as the jackknife diving and observations within tranquil waters of first encounters. A full leafed tree leans forward, a voyeur, an avid list into teenaged expectations. The tidy shingle has no clutter, no preconceptions of angst or roughness. A magic carpet towel is forward of the girls to dare the boys’ access, lest they have the courage to trespass on their territory. Lewis’ crooked tail cat is oblivious to the tease, and his crooked ash can denotes some cockeyed teenage thinking. Innocence is as fresh and untainted as Beach Open.

Bang - 36 x 24" by Michael Lewis

“Tribute to George Grosz.”

~ Michael Lewis

M One of his paintings was a guy sitting outdoors with a liquor bottle. That’s sort of this set up.

D He’s got a dummy on one knee. Is that a plastic heart on the table?

M Could be a real heart.

D Chained to his waist. And a mask.

M His hand is holding the mask.

D I like that you put Grosz there. Who’s the little puppy dog?

M Just a little puppy dog.

D And a Gap head. A pink balloon head.

Bang is a complex work, heralding George Grosz’ 1919 painting, ‘Café’ with many other Lewis fascinations luring and enthralling (archetypes, gumshoes, comic stripping) included in this composition. Lewis’ work is a composite of café cultural anomalies, the single guy lying in wait, the solo drunk, the incongruity of masking one’s true nature in public), a decoy, really, with his thoughts about popular fiction in various media pitched, projecting in the painting’s structure.

He entices us to join him at a table with a precarious liquor bottle and gun that is a toy with ‘Bang’ printed on an extending cloth, assuring us of distraction and appeasing us, that this might not be a too dangerous proffer. Detective fiction as a Tracy doll sits propped in the embrace of a chequered suit, vivid yellow and orange squares that would work best as a floor in a café, rather than as a patron’s suit fabric, sharp wariness embodied. The masking off, held aside corroborates rather than dispelling the sway of the painting’s earnest clowning. Droll, the man that has advances, plays a comic functionary role wears a red orange tie flag pointing out, warning us of a ruse. Oblivious tomfoolery is muddling as the complicated checks that blind us, distract Lewis’ intent in his intricate portrait.

A balloon on a stick for a head and neck, a little small proportionately for this yellow gloved, embellished body is pink as Bazooka bubble gum.

Behind the café dweller, lavender walks point to his slight neck, a vice, street ends as wits’ ends. The walks hold buildings with windows that view the scene on the left, and the right bricked construction shows a tricky and outlying escape to a TV room. A tiny sun echoes the colours Lewis has painted as the seated figure’s attire, the latter being more vividly conspicuous than the sunshine.

The portrait’s heart lays exposed on the table. A woman cut off from the entire picture plane walks a crooked tailed terrier, blending into the orangey hues, but a symbol of the terror of any male that is uncomfortable with his persona. The outlandishly costumed is too encumbered to do more than stare desirously, signified by his bauble head. The clowning, the impediments of his preoccupations shows the poser to be awkwardly positioned, and the bang is the subterfuge, his self deception .He is in finery as fiery as a café designer might employ to enable guests enjoy their surroundings but leave as quickly as possible. The fellow fires ineffectual mixed messages, is bamboozled. Lewis discharges impossible relational hope. Lewis paints how self deception is obvious to all that encounter it except to the individual experiencing his private, inhibiting feat toys, at first. One’s eventual self realization becomes a bang to be set on the table.

French Kris - 15 x 30" by Michael Lewis

“Captain of the Dandy Pucker”

~ Michael Lewis

D Which mask of the Italian masks is that?

M What I was thinking, because these are both from Sea Czar City, from the story, when I thought of him, I thought of Scaramouch [9], from Comedia d’ell arte . I really liked the long nose.

D It makes you think of Italian, not French, but he is masked.

Lewis has painting another of his Sea Czar invented characters in his online narrative. French Kris, captain of the Dandy Pucker meets his eventual reprisal with Cutlass Kate slicing off his masked nose:

“At dawn, we finally chased the Pucker down.

There was much cannon fire and grappling.

In fact Cutless Kate was in such a snit, she nearly drew blood for the first time.

She gave The Mask a nose bob and something smelly was revealed.

The Mask and French Kris were indeed one in the game. Bubbles was released from the bath. The Dandy Pucker was sent on its way with the fishes and one romance was a flounder.” [10] .

Lewis disguised French Kris in a Scaramouch mask. The mask is appropriate for Lewis’ character. French composer, Darius Milhaud composed Scaramouche for the theatre, Op. 165b, named after the Théâtre Scaramouche that produced children’s productions created by Henri Pascar.[1]. Lewis’ French Kris, and his other Sea Czar characters induce childlike trust in their existence. There were also several movies with Scaramouche titles, leads in the early movies, often based on Rafael Sabatini’s novels of adventure and romance. In the 17th century Comedia d’ell arte, created by Tiberio Fiorilli he is known to entertain by “grimaces and affected language". Apparently the story goes that he was beaten by Harlequin for his boasting and cowardice. [11] Cutlass Kate befits Harlequin in the Sea Czar story.

“It is said that one day, when the two-year-old Dauphin cried (the future Louis XIV), Fiorilli, as Scaramouche, made any possible sound to comfort him. He achieved this task with grimaces and tomfoolery; consequently, the Dauphin had "a need, that he had at the time, the hands and the dress of Scaramouche". Fiorilli was then ordered to visit the court every night to amuse the Dauphin, which helped the Scaramouche character become a stock figure in the theatre of the time.” [12]

Lewis painted the swashbuckler with a grimacing red mask and one can imagine, affected language, posing with dandyish strippy pants and a grand sword. One can imagine this is a character from a silent movie made Technicolor, challenging his dignity ‘by crook(edness) or by rapier, matey’. Well, Cutlass Kate had a different idea. French Kris was foiled. Lewis paints him as he might like to be remembered, before the dismemberment of his mask nose. Lewis eloquently paints vainglory.

Sea Shanty - 22 x 28" by Michael Lewis

“There is a place I call Sea Czar City. It resides only in my pun-addled brain. It is a kind of Never-Never land by way of Dogpatch. This is one of the ways I get there.”

~ Michael Lewis

M Again, this is from Sea Czar city, the blog with the puns. It started to become an imaginative place in my head that was becoming a little bit like Sydney, a little bit like Victoria, like other places I have been and kids fairy books.

D The boat’s name is Sea Shanty. The title of the work is Sea Shanty.

M Because that is the boat. The boat is the way into the city.

D Right, Because you have these open gates that are only boat accessible. You have a mermaid that is much nicer looking than the other one. But her tail is the bridge of a chest, with rib bones. Then you have a fish jumping up that could be Jeep’s cousin. The pilot of the boat is a shadow.

M By way of dogpatch

D Tell me about dogpatch?

M Dogpatch is L’il Abner’s town again, Sunday Funnies. I always liked Dogpatch. It is supposed to be this fallen down poor town in the Ozarks. It is where the comic strip was set. Fallen down buildings. It must have had a huge impact on me as a kid. Most of my dreamscapes are wooden buildings that are askew and falling down. I seem to be very comfortable in my head in that kind of mindscape.

D Its delightful how you bring that into the work. It’s also very German Expressionist.

M That’s also reflecting my three huge influences, including. Robert Ben Shahn. William Gropper. Social Realists of the 30s.

Sea Shanty is about a journey’s conclusion, returning to intimate familiarity. Lewis names the vehicle of his travels Sea Shanty, shanty, a sailor’s work song, or a ramshackle building. The boat has access to its destination, by way of a gate to the town on the edge of the sea. Al Cap’s ‘Dogpatch’, a poor, broken down place with ineffectual people, Lewis tells us (above) is the inspired destination. Lewis, during his childhood invested a lot of time in ‘Dogpatch’, because he enjoyed Lil’Abner, Capp’s comic. The town painted in Sea Shanty is not at all crude. Neither is the boat bleak.

What one can deduce is that Lewis has transformed the mutability and convolution of humanity’s utmost compromised folks and their reciprocating local(s) into intriguing and quaint characterization, à la Victoria/Sydney, imaginatively. He shows his love of all human contrived oddities and that he can be at home in the mires of intrigue, which can be vibrant and joyful, if only you let it draw you to its vibrancy. His work shows how, if you engage kindly with the untoward, one day it can be the best incentive to welcome the convoluted hospitably within memory’s fray, which isn’t all that bad, in retrospect, allowing the establishment of the blue clear skies of enduring contentment.

Gallerist - guess how many weapons in the paintings without looking. Lots of weapons.

M Without looking?

D Do we count paint brushes as weapons?

M The plane is a weapon.

D The ocean is a weapon because it killed a man.

Gallerist - 20.

D Many weapons to fight inconsistency, to fight for the underdog.

[1] http://www.allmusic.com/composition/scaramouche-3-suite-for-2-pianos-op-165b-mc0002364142

No comments:

Post a Comment