Monday, June 9, 2014

Erik Volet - Scene from the Yiddish Theatre & Other Paintings – review

Erik Volet

Scene from the Yiddish Theatre & Other Paintings

1-15 June 2014

Erik Volet - Exhibit-v Interview

Ministry of Casual Living

819 Fort Street

Victoria BC

Review by Debora Alanna

The theater, bringing impersonal masks to life, is only for those who are virile enough to create new life: either as a conflict of passions subtler than those we already know, or as a complete new character.

~ Alfred Jarry (1873-1907). “Twelve Theatrical Topics “, Topic 4, in Dossiers Caneles du college de pataphysique, no 5. (Paris, 1960: rep in Selected Works of Alfred Jarry, ed. by Roger Shattuck and Simon Watson Taylor, 1965).

Erik Volet entitled his current exhibition at the Ministry of Casual Living (MOCL), Scene from the Yiddish Theatre & Other Paintings. Large paintings are images gleaned from historical photographs. Yiddish culture, specifically a Purim speil (play) performed in a home is titled Scene from the Yiddish Theatre. A communal meal illustrates uncertainty about being bound to classification that religion, disease and poverty involves appears inBeggars Banquet. Alfred Jarry upon his velo in Alfortville is Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry and Jarry carrying a boat with another Volet titled, Jarry Carring the Skiff. Included in this exhibition are painting investigations diverging from the Yiddish and Jarry contexts, distinct cultural pondering also from photographs or photographic references - Stolen Journey and Khmer Dancers. An oblique reference to “Portrait of Fernando Pessoa” by Jose de Almanda-Negreiros, 1954 is transformed into Volet’sTeetotaller in the Saloon.

Learned, vivid essays by John Luna and Astrid Wright distinguish Volet’s exhibition catalogue.

![clip_image002[1] clip_image002[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH9_kMwsNOCmLdOqTbW0bDo1_VIJ_DaTPni-dwWP1VzvvD226exaNoT5TIHvbx3tpT_1vBwotB9IEJSouyrBlQaWiTbf2d9U2LOHcDRWtHoiJ4xdfblROcM7k8UZBFJTWoR-AZRg/?imgmax=800)

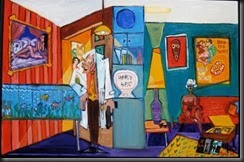

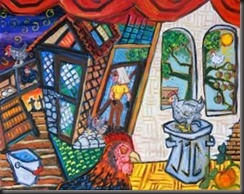

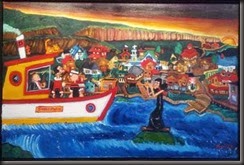

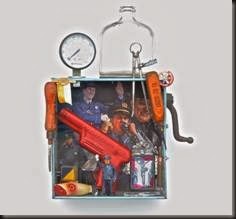

Scene from the Yiddish Theatre - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas - 4 x 6’

Borrowing from Jarry’s Topic 4 (above), Volet allows import and disquiet of his personal response to the outwardly impersonal presence within photographic masks. Masking or obfuscation of what may have been personal for the people within the photos seen in books and articles as uncertain subjects that evoke narrative descriptions complementing texts cultivate a performance with Volet’s use and transformation of these images. He involves us in impalpable conflicts between diligence and enthusiasm, desire and idealised devotion. Volet creates new portrayals, portals into and from historical, cultural reverence of a detained, ponderous existence.

Enlarged venerated images impose because realms of significance extend beyond an original photograph or a photo on a printed page, outside the scope of appropriation and reproduction. The work, Scene from the Yiddish Theatre becomes an entrancing introduction from which to view the entire show. The pretext for comic dramatization by children during the Purim festival, Purimshpiln, allows a vehicle to play out the repercussions of chance and or coincidence (Pur means lottery [1] – an astrological forecast indicating when Jews were most vulnerable 2500 years ago in Persia) is a means to reveal hidden natures and true characters as described in the Book of Ester. Hiding one’s true nature, our essential character, still plagues the human condition and the guise of acting out intention through dramatic play available to children seems enviable. Volet questions fundamental import, what plays out, in when drawn existing within the tragic-comic human condition.

A weakened adult audience is sullen to the left of the animated players that are greater than the sideliners. Volet paints a monochrome that evokes an intention to cultivate mirth and meaning from whatever is at hand, a Les Arts Incohérents’ saucy satire. To be an audience alone is a grave and improbable, impoverished existence. Ingenuousness is lively and teases out what can be impossible to discover without the lark.

![clip_image004[1] clip_image004[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiXaug8ZWBeNbkTxO2dBZ4N8xe6n7NXTojJ7yvIjRv3w3Lxexx8UEExaL91hh5f3-z9AlYxTKQCWRYuPGqG07ZdUPLMRezio2NRbqWZKVomQDh7z7X96qvyGq9USCxVm0yr6iCvAg/?imgmax=800)

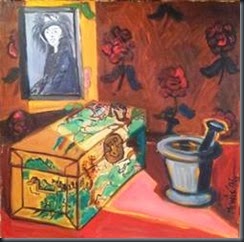

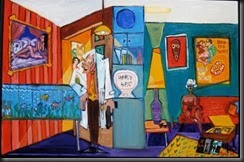

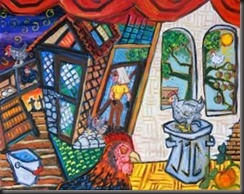

Beggars Banquet - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas – 4 x 5’

And when i search a faceless crowd

a swirling mass of gray and

black and white

they don't look real to me

in fact, they look so strange

~ Chorus from “Salt Of The Earth”. Rolling Stones. Album: Beggars Banquet - 1968

Volet continues to wield and vanquish, to sport and supplant histories with grey scales.Beggars Banquet is saturated with shadows using severe black and testaments of grey, frightening white, a social chiaroscuro shows a meagre table, set for seemingly rustic if not rural, diners, possibly a group of pre - 20th century moujik. The close diagonal table corner points at us, inviting us to join the motley group. A distant male figure, far right watches our approach. Volet weighs qualities of humanity.

Utilizing a still from Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana, Volet chose the moment where Viridiana, a novice nun attempts charity before her eventual sexual entanglements in the movie. The image is not a banquet of bliss availed by religious order but the abundant dearth of religion. Volet’s use of the Buñuel sardonic wink at charity’s anarchy includes us, his audience in the caper.

The front right featured guest at the Beggars Banquet is a leper being assessed by religious order. His arm held to ascertain the degree of his leprosy, a nun examines his appendage, presumably the man’s ability to eat, degree of degeneration. The diners pause their repast. The nun’s sidelong glare dominates the mood of the work more than a supposed leprosy might. Volet paints the groups’ general stilled acquiesce. What else can they do, being stilled? Religious arraignment presides for this second. Eroticism ensues in Buñuel’s version. Volet sustains our suspense.

Volet’s table is spare. Dishes are empty. People sitting left of the picture plane past the nun’s scrutiny are undersized, their influence on the event diminished. A wide unlit rear fireplace is a grotto of unidentified depths. The work is shrouded in poverty. Volet paints the impoverished mind, where proof is required to trust. Depleted spirits hungry for purpose are preoccupied with the provocation of an outsiders’ probing. The nun’s garb tone equals the others. She too is suppliant, although presumptuous of the import of her role. We question the arbiter’s questioning. Sumptuous black blocks, withholds information, starves us while testing our patience like anyone at the table.

Christian Metz’s 1978 publication, “Essais sur la Signification au Cinéma “.Vol. 2, p. 23 writes that the cinematic screen masks and frames, conceals and structures, limiting the viewer’s understanding of the image(s) to direct attention, construct tension. We cannot know the whole story Volet paints, only what he chooses to show us. Volet feeds us dramatic irony to appease our need for narration, our discomfort and willing separation from the implausibility of poverty. Who would willingly condescend to sit with pariahs or associate with the needy? What is their need to transgress boundaries of propriety?

The banquet is Volet’s offering of intrigue. He invites us to the banquet because we are the disadvantaged, the leper, consuming insignificance, one of the indistinguishable at an empty table. We need explanation to be confident in our separateness from social injustice. In Beggars Banquet we can see the people are out of our time, out of our experience, and can attribute the indefinite or unfamiliar to otherness, black and white thinking. We participate in a banquet of existential apartness when we are strangers to the ambiguous, reject vagueness as unreal, segregate ourselves from others’ chronicles. We take comfort in our separation from the outmoded or obsolete scene we can assert is strange - to most of us - relative to the comforts afforded by Western Civilization, unknowable, a poor table. We are the unrequited guest at Beggars Banquet. Our requisite is Volet’s silent subterfuge.

Publications originating from the Paris Collège de 'Pataphysique are collectively calledViridis Candela ("green candle") [2]. Two of Volet’s works have a green candle glow (Beggars Banquet stars Viridiana, provides another green reference), an impossible luminous intensity that might be seen to oppose the quaint as a sepia toned film still might conjoin to an idealized nostalgia, a protanopia monochrome articulating the past in the presence of a cycling Alfred Jarry, rex inutilis (useless king) capitulated in a Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry where Volet captures and surrenders to the king of incredulity. Volet yields to Jarry’s cyclist soul requiring the joy and antics possible on that vehicle that propelled the instigator of a “science of imaginary solutions” [3] (pataphysics). Volet’s painted treatment of the solitary cyclist, Jarry shows the image copied from the with shut eyes, turning a historic author into a blind moving time traveller, epitomized by the artist’s explorer machinations as painted egress.

![clip_image006[1] clip_image006[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhuIuflE8nY9OgwlmE922GR1REWsowfLwStj3JCQdJwTTB_wrmb4L5geqo3STk8D9DxZIifFet4s6WXsi-30bpg5Q2k38dATBmi0Gg96R0K0ru3GIvppV-A900bVF52WxJ44i9V_g/?imgmax=800)

Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas – 4 x 5’

![clip_image008[1] clip_image008[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgBwsd8c5vGH_coGkiMnyzxShptid8Za_qAzrCXIXwhAtS2cEXJP02r84BPkzKpU0loX5scepv-KgNK01rCsdsu-ZvbqrDX-KMS05Jl90U9Olk_8_ewc2Mqs7rKtKWpq1nDIfIRvA/?imgmax=800)

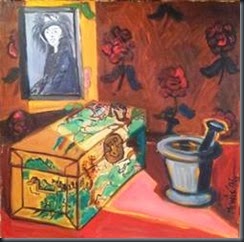

Erik Volet - MOCL Gallery installation. June 2014

![clip_image010[1] clip_image010[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiFDfvu8F5nUx-_ij4o0DGNBtyL5YaHvfq3ACJfZkQFAxB5cwhQOoSN25AwqdS3bTRiO2Gb8F2OLJZDhpr7QLsERE_q6FFxI4k29bkNhDjKD9MywgFlX-psvATuNxoaz9A2FULG-w/?imgmax=800)

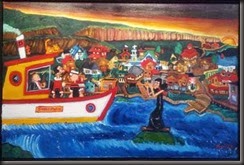

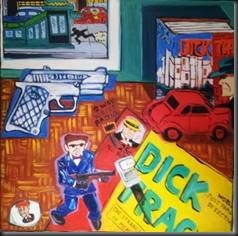

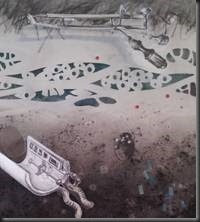

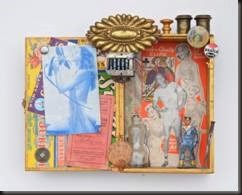

Teetotaler in the Saloon - Erik Volet - Oil on Canvas – 3 x 4’

Although this work is definitive without the mushing, pulpy sentimentality of either e.g. a Dorothea Tanning transience, or a Marc Chagall floating figure sensibility , Teetotaler in the Saloon evokes thoughts of both presentations. We find corporeal incongruity to be normalcy. A Pieter Brueghel the elder multiplex of scenes, with a van Gogh / Issac Abrams colour palate, Volet’s opposing ceruleans and oranges strike the eye with the compunction of a bright but conflicting conscience one wishes one could leave in a public place to be stolen but cannot forgetten. The gangly tea drinker is suspended in disbelief with what surrounds him, unbearable legs extending from the round central tabletop. Allusions to this figure is echoed with a floor inclined body and a fellow entering a yellow oval in the back (ideal future sunniness), sauntering to a peeking cast behind the red drape. Temporal extensions are saloon dwellers in front of a red curtain, a staging of saloon/cafe culture. These are social tests for the solo hatted studier of mores in several poses. Teetotaler is every man, everywhere. Teetotaler is anyone’s mind rejoining coloured contradictions.

André Breton spoke about Meret Oppenheim’s ‘use values’ redefined, the rational concerning her work to generate disorientation, impose surreal functions with objects, noted by Josef Helfenstein in “Against the intolerability of fame: Meret Oppenheim and Surrealism” in ‘‘Beyond the Teacup,’’ p. 24, ed. by Jacqueline Burkhardt and Bice Curiger (New York: Independent Curators Incorporated, 1996), p 29. Volet’s teetotaller is fuzzy, tea an obfuscation device, the mental confusion of the tea drinker. He interprets isolation in social settings that might be seen through a quote attributed to Rat Pack member, Dean Martin, “King of Cool” (American actor and singer. 1917-1995) know for his extensive alcohol consumption, “I'd hate to be a teetotaler. Imagine getting up in the morning and knowing that's as good as you're going to feel all day.”

Volet’s teetotaler looks sober, bearing the vesture of distraction and mystification, the result of abstemiousness. The character absents himself from communal interaction, judicious, perhaps accepting what Alfred Jarry wrote in La Revue Blanche, 1897, "It is because the public are a mass—inert, obtuse, and passive—that they need to be shaken up from time to time so that we can tell from their bear-like grunts where they are—and also where they stand. They are pretty harmless, in spite of their numbers, because they are fighting against intelligence." Volet’s main character’s legs describe a person that does not easily withstand anything or cannot assert his will. This teetotaler partakes in his populated ruminations instead, an impalpable place.

![clip_image012[1] clip_image012[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhIC82Zd8b7l3-_f3k2a9ouhuj01QK8vKAmnp7UBJAKauyDMl4wV5JVAKBqSU4o-w3PutTd4tjtmw_ZldEFfoM3O-wiZk3YvKtD8TVtAAgFHup3ltW1kFomMufylM4d4RW2EzrmfA/?imgmax=800)

Erik Volet - MOCL Gallery installation

We move in the direction of Time and at the same speed, being ourselves part of the Present. If we could remain immobile absolute Space while Time elapses, if we could lock our selves inside a Machine that isolates us from Time (except for the small and normal "speed of duration" that will stay with us because of inertia), all future and past instants could be explored successively, just as the stationary spectator of a panorama has the illusion of a swift voyage through a series of landscapes. (We shall demonstrate later that, as seen from the Machine, the Past lies beyond the Future.)

(...)

Duration is the transformation of a succession into a reversion.

In other words:

THE BECOMING OF A MEMORY.

~ Alfred Jarry. “How to Construct a Time Machine”. Selected Works of Alfred Jarry, edited by Roger Shattuck & Simon Watson Taylor, New York, Grove Press (1965, 1980)

Volet’s exhibition evokes the divergent Alfred Jarry’s 1899 instructions, “How to Construct a Time Machine” (tr. by Roger Shattuck). Volet gathers us in the MOCL time capsule so we may contemplate the future and past, photographic evidence transpires through Volet’s painted evaluations of time and space, a simultaneous opportunity to investigate contradictory lives and confirm what may lay beyond his panoramas.

Through his populated landscapes we understand how Volet penetrates and eludes denouncement of devout palaver by dramatically enlarging reproductions of varied loci. He extends images to enlarge space, preventing insular thinking, frustrate inertia, complacency. Volet’s need to expand historical imagery renders and surmounts cultural ambivalence with his large works, mainly monochrome to simplify allowing commensurability. Volet realizes concurrent elasticity and unyielding phenomena. He paints an intense concentration of impossible human viscosity, thick sticky human consciousness, the banal, the poetic. Volet has succeeded in converting his reevaluations into cogent, illusory resolutions, striking transformations. Obdurate memory becomes Volet’s rejoinder. Kings would would proffer a toast.

[1]http://jafi.org/JewishAgency/English/Jewish+Education/Compelling+Content/Jewish+Time/Festivals+and+Memorial+Days/Purim/PUR+PURIM+The+Source+and+the+Meaning+of+the+Term.htm

[2] Hugill, Andrew (2012). 'Pataphysics: A useless guide. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01779-4

[3] http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/public/article1246470.ece

Scene from the Yiddish Theatre & Other Paintings

1-15 June 2014

Erik Volet - Exhibit-v Interview

Ministry of Casual Living

819 Fort Street

Victoria BC

Review by Debora Alanna

The theater, bringing impersonal masks to life, is only for those who are virile enough to create new life: either as a conflict of passions subtler than those we already know, or as a complete new character.

~ Alfred Jarry (1873-1907). “Twelve Theatrical Topics “, Topic 4, in Dossiers Caneles du college de pataphysique, no 5. (Paris, 1960: rep in Selected Works of Alfred Jarry, ed. by Roger Shattuck and Simon Watson Taylor, 1965).

Erik Volet entitled his current exhibition at the Ministry of Casual Living (MOCL), Scene from the Yiddish Theatre & Other Paintings. Large paintings are images gleaned from historical photographs. Yiddish culture, specifically a Purim speil (play) performed in a home is titled Scene from the Yiddish Theatre. A communal meal illustrates uncertainty about being bound to classification that religion, disease and poverty involves appears inBeggars Banquet. Alfred Jarry upon his velo in Alfortville is Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry and Jarry carrying a boat with another Volet titled, Jarry Carring the Skiff. Included in this exhibition are painting investigations diverging from the Yiddish and Jarry contexts, distinct cultural pondering also from photographs or photographic references - Stolen Journey and Khmer Dancers. An oblique reference to “Portrait of Fernando Pessoa” by Jose de Almanda-Negreiros, 1954 is transformed into Volet’sTeetotaller in the Saloon.

Learned, vivid essays by John Luna and Astrid Wright distinguish Volet’s exhibition catalogue.

![clip_image002[1] clip_image002[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH9_kMwsNOCmLdOqTbW0bDo1_VIJ_DaTPni-dwWP1VzvvD226exaNoT5TIHvbx3tpT_1vBwotB9IEJSouyrBlQaWiTbf2d9U2LOHcDRWtHoiJ4xdfblROcM7k8UZBFJTWoR-AZRg/?imgmax=800)

Scene from the Yiddish Theatre - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas - 4 x 6’

Borrowing from Jarry’s Topic 4 (above), Volet allows import and disquiet of his personal response to the outwardly impersonal presence within photographic masks. Masking or obfuscation of what may have been personal for the people within the photos seen in books and articles as uncertain subjects that evoke narrative descriptions complementing texts cultivate a performance with Volet’s use and transformation of these images. He involves us in impalpable conflicts between diligence and enthusiasm, desire and idealised devotion. Volet creates new portrayals, portals into and from historical, cultural reverence of a detained, ponderous existence.

Enlarged venerated images impose because realms of significance extend beyond an original photograph or a photo on a printed page, outside the scope of appropriation and reproduction. The work, Scene from the Yiddish Theatre becomes an entrancing introduction from which to view the entire show. The pretext for comic dramatization by children during the Purim festival, Purimshpiln, allows a vehicle to play out the repercussions of chance and or coincidence (Pur means lottery [1] – an astrological forecast indicating when Jews were most vulnerable 2500 years ago in Persia) is a means to reveal hidden natures and true characters as described in the Book of Ester. Hiding one’s true nature, our essential character, still plagues the human condition and the guise of acting out intention through dramatic play available to children seems enviable. Volet questions fundamental import, what plays out, in when drawn existing within the tragic-comic human condition.

A weakened adult audience is sullen to the left of the animated players that are greater than the sideliners. Volet paints a monochrome that evokes an intention to cultivate mirth and meaning from whatever is at hand, a Les Arts Incohérents’ saucy satire. To be an audience alone is a grave and improbable, impoverished existence. Ingenuousness is lively and teases out what can be impossible to discover without the lark.

![clip_image004[1] clip_image004[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiXaug8ZWBeNbkTxO2dBZ4N8xe6n7NXTojJ7yvIjRv3w3Lxexx8UEExaL91hh5f3-z9AlYxTKQCWRYuPGqG07ZdUPLMRezio2NRbqWZKVomQDh7z7X96qvyGq9USCxVm0yr6iCvAg/?imgmax=800)

Beggars Banquet - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas – 4 x 5’

And when i search a faceless crowd

a swirling mass of gray and

black and white

they don't look real to me

in fact, they look so strange

~ Chorus from “Salt Of The Earth”. Rolling Stones. Album: Beggars Banquet - 1968

Volet continues to wield and vanquish, to sport and supplant histories with grey scales.Beggars Banquet is saturated with shadows using severe black and testaments of grey, frightening white, a social chiaroscuro shows a meagre table, set for seemingly rustic if not rural, diners, possibly a group of pre - 20th century moujik. The close diagonal table corner points at us, inviting us to join the motley group. A distant male figure, far right watches our approach. Volet weighs qualities of humanity.

Utilizing a still from Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana, Volet chose the moment where Viridiana, a novice nun attempts charity before her eventual sexual entanglements in the movie. The image is not a banquet of bliss availed by religious order but the abundant dearth of religion. Volet’s use of the Buñuel sardonic wink at charity’s anarchy includes us, his audience in the caper.

The front right featured guest at the Beggars Banquet is a leper being assessed by religious order. His arm held to ascertain the degree of his leprosy, a nun examines his appendage, presumably the man’s ability to eat, degree of degeneration. The diners pause their repast. The nun’s sidelong glare dominates the mood of the work more than a supposed leprosy might. Volet paints the groups’ general stilled acquiesce. What else can they do, being stilled? Religious arraignment presides for this second. Eroticism ensues in Buñuel’s version. Volet sustains our suspense.

Volet’s table is spare. Dishes are empty. People sitting left of the picture plane past the nun’s scrutiny are undersized, their influence on the event diminished. A wide unlit rear fireplace is a grotto of unidentified depths. The work is shrouded in poverty. Volet paints the impoverished mind, where proof is required to trust. Depleted spirits hungry for purpose are preoccupied with the provocation of an outsiders’ probing. The nun’s garb tone equals the others. She too is suppliant, although presumptuous of the import of her role. We question the arbiter’s questioning. Sumptuous black blocks, withholds information, starves us while testing our patience like anyone at the table.

Christian Metz’s 1978 publication, “Essais sur la Signification au Cinéma “.Vol. 2, p. 23 writes that the cinematic screen masks and frames, conceals and structures, limiting the viewer’s understanding of the image(s) to direct attention, construct tension. We cannot know the whole story Volet paints, only what he chooses to show us. Volet feeds us dramatic irony to appease our need for narration, our discomfort and willing separation from the implausibility of poverty. Who would willingly condescend to sit with pariahs or associate with the needy? What is their need to transgress boundaries of propriety?

The banquet is Volet’s offering of intrigue. He invites us to the banquet because we are the disadvantaged, the leper, consuming insignificance, one of the indistinguishable at an empty table. We need explanation to be confident in our separateness from social injustice. In Beggars Banquet we can see the people are out of our time, out of our experience, and can attribute the indefinite or unfamiliar to otherness, black and white thinking. We participate in a banquet of existential apartness when we are strangers to the ambiguous, reject vagueness as unreal, segregate ourselves from others’ chronicles. We take comfort in our separation from the outmoded or obsolete scene we can assert is strange - to most of us - relative to the comforts afforded by Western Civilization, unknowable, a poor table. We are the unrequited guest at Beggars Banquet. Our requisite is Volet’s silent subterfuge.

Publications originating from the Paris Collège de 'Pataphysique are collectively calledViridis Candela ("green candle") [2]. Two of Volet’s works have a green candle glow (Beggars Banquet stars Viridiana, provides another green reference), an impossible luminous intensity that might be seen to oppose the quaint as a sepia toned film still might conjoin to an idealized nostalgia, a protanopia monochrome articulating the past in the presence of a cycling Alfred Jarry, rex inutilis (useless king) capitulated in a Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry where Volet captures and surrenders to the king of incredulity. Volet yields to Jarry’s cyclist soul requiring the joy and antics possible on that vehicle that propelled the instigator of a “science of imaginary solutions” [3] (pataphysics). Volet’s painted treatment of the solitary cyclist, Jarry shows the image copied from the with shut eyes, turning a historic author into a blind moving time traveller, epitomized by the artist’s explorer machinations as painted egress.

![clip_image006[1] clip_image006[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhuIuflE8nY9OgwlmE922GR1REWsowfLwStj3JCQdJwTTB_wrmb4L5geqo3STk8D9DxZIifFet4s6WXsi-30bpg5Q2k38dATBmi0Gg96R0K0ru3GIvppV-A900bVF52WxJ44i9V_g/?imgmax=800)

Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas – 4 x 5’

![clip_image008[1] clip_image008[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgBwsd8c5vGH_coGkiMnyzxShptid8Za_qAzrCXIXwhAtS2cEXJP02r84BPkzKpU0loX5scepv-KgNK01rCsdsu-ZvbqrDX-KMS05Jl90U9Olk_8_ewc2Mqs7rKtKWpq1nDIfIRvA/?imgmax=800)

Erik Volet - MOCL Gallery installation. June 2014

![clip_image010[1] clip_image010[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiFDfvu8F5nUx-_ij4o0DGNBtyL5YaHvfq3ACJfZkQFAxB5cwhQOoSN25AwqdS3bTRiO2Gb8F2OLJZDhpr7QLsERE_q6FFxI4k29bkNhDjKD9MywgFlX-psvATuNxoaz9A2FULG-w/?imgmax=800)

Teetotaler in the Saloon - Erik Volet - Oil on Canvas – 3 x 4’

Although this work is definitive without the mushing, pulpy sentimentality of either e.g. a Dorothea Tanning transience, or a Marc Chagall floating figure sensibility , Teetotaler in the Saloon evokes thoughts of both presentations. We find corporeal incongruity to be normalcy. A Pieter Brueghel the elder multiplex of scenes, with a van Gogh / Issac Abrams colour palate, Volet’s opposing ceruleans and oranges strike the eye with the compunction of a bright but conflicting conscience one wishes one could leave in a public place to be stolen but cannot forgetten. The gangly tea drinker is suspended in disbelief with what surrounds him, unbearable legs extending from the round central tabletop. Allusions to this figure is echoed with a floor inclined body and a fellow entering a yellow oval in the back (ideal future sunniness), sauntering to a peeking cast behind the red drape. Temporal extensions are saloon dwellers in front of a red curtain, a staging of saloon/cafe culture. These are social tests for the solo hatted studier of mores in several poses. Teetotaler is every man, everywhere. Teetotaler is anyone’s mind rejoining coloured contradictions.

André Breton spoke about Meret Oppenheim’s ‘use values’ redefined, the rational concerning her work to generate disorientation, impose surreal functions with objects, noted by Josef Helfenstein in “Against the intolerability of fame: Meret Oppenheim and Surrealism” in ‘‘Beyond the Teacup,’’ p. 24, ed. by Jacqueline Burkhardt and Bice Curiger (New York: Independent Curators Incorporated, 1996), p 29. Volet’s teetotaller is fuzzy, tea an obfuscation device, the mental confusion of the tea drinker. He interprets isolation in social settings that might be seen through a quote attributed to Rat Pack member, Dean Martin, “King of Cool” (American actor and singer. 1917-1995) know for his extensive alcohol consumption, “I'd hate to be a teetotaler. Imagine getting up in the morning and knowing that's as good as you're going to feel all day.”

Volet’s teetotaler looks sober, bearing the vesture of distraction and mystification, the result of abstemiousness. The character absents himself from communal interaction, judicious, perhaps accepting what Alfred Jarry wrote in La Revue Blanche, 1897, "It is because the public are a mass—inert, obtuse, and passive—that they need to be shaken up from time to time so that we can tell from their bear-like grunts where they are—and also where they stand. They are pretty harmless, in spite of their numbers, because they are fighting against intelligence." Volet’s main character’s legs describe a person that does not easily withstand anything or cannot assert his will. This teetotaler partakes in his populated ruminations instead, an impalpable place.

![clip_image012[1] clip_image012[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhIC82Zd8b7l3-_f3k2a9ouhuj01QK8vKAmnp7UBJAKauyDMl4wV5JVAKBqSU4o-w3PutTd4tjtmw_ZldEFfoM3O-wiZk3YvKtD8TVtAAgFHup3ltW1kFomMufylM4d4RW2EzrmfA/?imgmax=800)

Erik Volet - MOCL Gallery installation

We move in the direction of Time and at the same speed, being ourselves part of the Present. If we could remain immobile absolute Space while Time elapses, if we could lock our selves inside a Machine that isolates us from Time (except for the small and normal "speed of duration" that will stay with us because of inertia), all future and past instants could be explored successively, just as the stationary spectator of a panorama has the illusion of a swift voyage through a series of landscapes. (We shall demonstrate later that, as seen from the Machine, the Past lies beyond the Future.)

(...)

Duration is the transformation of a succession into a reversion.

In other words:

THE BECOMING OF A MEMORY.

~ Alfred Jarry. “How to Construct a Time Machine”. Selected Works of Alfred Jarry, edited by Roger Shattuck & Simon Watson Taylor, New York, Grove Press (1965, 1980)

Volet’s exhibition evokes the divergent Alfred Jarry’s 1899 instructions, “How to Construct a Time Machine” (tr. by Roger Shattuck). Volet gathers us in the MOCL time capsule so we may contemplate the future and past, photographic evidence transpires through Volet’s painted evaluations of time and space, a simultaneous opportunity to investigate contradictory lives and confirm what may lay beyond his panoramas.

Through his populated landscapes we understand how Volet penetrates and eludes denouncement of devout palaver by dramatically enlarging reproductions of varied loci. He extends images to enlarge space, preventing insular thinking, frustrate inertia, complacency. Volet’s need to expand historical imagery renders and surmounts cultural ambivalence with his large works, mainly monochrome to simplify allowing commensurability. Volet realizes concurrent elasticity and unyielding phenomena. He paints an intense concentration of impossible human viscosity, thick sticky human consciousness, the banal, the poetic. Volet has succeeded in converting his reevaluations into cogent, illusory resolutions, striking transformations. Obdurate memory becomes Volet’s rejoinder. Kings would would proffer a toast.

[1]http://jafi.org/JewishAgency/English/Jewish+Education/Compelling+Content/Jewish+Time/Festivals+and+Memorial+Days/Purim/PUR+PURIM+The+Source+and+the+Meaning+of+the+Term.htm

[2] Hugill, Andrew (2012). 'Pataphysics: A useless guide. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01779-4

[3] http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/public/article1246470.ece

Monday, June 9, 2014

Erik Volet - Scene from the Yiddish Theatre & Other Paintings – review

Erik Volet

Scene from the Yiddish Theatre & Other Paintings

1-15 June 2014

Erik Volet - Exhibit-v Interview

Ministry of Casual Living

819 Fort Street

Victoria BC

Review by Debora Alanna

The theater, bringing impersonal masks to life, is only for those who are virile enough to create new life: either as a conflict of passions subtler than those we already know, or as a complete new character.

~ Alfred Jarry (1873-1907). “Twelve Theatrical Topics “, Topic 4, in Dossiers Caneles du college de pataphysique, no 5. (Paris, 1960: rep in Selected Works of Alfred Jarry, ed. by Roger Shattuck and Simon Watson Taylor, 1965).

Erik Volet entitled his current exhibition at the Ministry of Casual Living (MOCL), Scene from the Yiddish Theatre & Other Paintings. Large paintings are images gleaned from historical photographs. Yiddish culture, specifically a Purim speil (play) performed in a home is titled Scene from the Yiddish Theatre. A communal meal illustrates uncertainty about being bound to classification that religion, disease and poverty involves appears inBeggars Banquet. Alfred Jarry upon his velo in Alfortville is Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry and Jarry carrying a boat with another Volet titled, Jarry Carring the Skiff. Included in this exhibition are painting investigations diverging from the Yiddish and Jarry contexts, distinct cultural pondering also from photographs or photographic references - Stolen Journey and Khmer Dancers. An oblique reference to “Portrait of Fernando Pessoa” by Jose de Almanda-Negreiros, 1954 is transformed into Volet’sTeetotaller in the Saloon.

Learned, vivid essays by John Luna and Astrid Wright distinguish Volet’s exhibition catalogue.

![clip_image002[1] clip_image002[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH9_kMwsNOCmLdOqTbW0bDo1_VIJ_DaTPni-dwWP1VzvvD226exaNoT5TIHvbx3tpT_1vBwotB9IEJSouyrBlQaWiTbf2d9U2LOHcDRWtHoiJ4xdfblROcM7k8UZBFJTWoR-AZRg/?imgmax=800)

Scene from the Yiddish Theatre - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas - 4 x 6’

Borrowing from Jarry’s Topic 4 (above), Volet allows import and disquiet of his personal response to the outwardly impersonal presence within photographic masks. Masking or obfuscation of what may have been personal for the people within the photos seen in books and articles as uncertain subjects that evoke narrative descriptions complementing texts cultivate a performance with Volet’s use and transformation of these images. He involves us in impalpable conflicts between diligence and enthusiasm, desire and idealised devotion. Volet creates new portrayals, portals into and from historical, cultural reverence of a detained, ponderous existence.

Enlarged venerated images impose because realms of significance extend beyond an original photograph or a photo on a printed page, outside the scope of appropriation and reproduction. The work, Scene from the Yiddish Theatre becomes an entrancing introduction from which to view the entire show. The pretext for comic dramatization by children during the Purim festival, Purimshpiln, allows a vehicle to play out the repercussions of chance and or coincidence (Pur means lottery [1] – an astrological forecast indicating when Jews were most vulnerable 2500 years ago in Persia) is a means to reveal hidden natures and true characters as described in the Book of Ester. Hiding one’s true nature, our essential character, still plagues the human condition and the guise of acting out intention through dramatic play available to children seems enviable. Volet questions fundamental import, what plays out, in when drawn existing within the tragic-comic human condition.

A weakened adult audience is sullen to the left of the animated players that are greater than the sideliners. Volet paints a monochrome that evokes an intention to cultivate mirth and meaning from whatever is at hand, a Les Arts Incohérents’ saucy satire. To be an audience alone is a grave and improbable, impoverished existence. Ingenuousness is lively and teases out what can be impossible to discover without the lark.

![clip_image004[1] clip_image004[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiXaug8ZWBeNbkTxO2dBZ4N8xe6n7NXTojJ7yvIjRv3w3Lxexx8UEExaL91hh5f3-z9AlYxTKQCWRYuPGqG07ZdUPLMRezio2NRbqWZKVomQDh7z7X96qvyGq9USCxVm0yr6iCvAg/?imgmax=800)

Beggars Banquet - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas – 4 x 5’

And when i search a faceless crowd

a swirling mass of gray and

black and white

they don't look real to me

in fact, they look so strange

~ Chorus from “Salt Of The Earth”. Rolling Stones. Album: Beggars Banquet - 1968

Volet continues to wield and vanquish, to sport and supplant histories with grey scales.Beggars Banquet is saturated with shadows using severe black and testaments of grey, frightening white, a social chiaroscuro shows a meagre table, set for seemingly rustic if not rural, diners, possibly a group of pre - 20th century moujik. The close diagonal table corner points at us, inviting us to join the motley group. A distant male figure, far right watches our approach. Volet weighs qualities of humanity.

Utilizing a still from Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana, Volet chose the moment where Viridiana, a novice nun attempts charity before her eventual sexual entanglements in the movie. The image is not a banquet of bliss availed by religious order but the abundant dearth of religion. Volet’s use of the Buñuel sardonic wink at charity’s anarchy includes us, his audience in the caper.

The front right featured guest at the Beggars Banquet is a leper being assessed by religious order. His arm held to ascertain the degree of his leprosy, a nun examines his appendage, presumably the man’s ability to eat, degree of degeneration. The diners pause their repast. The nun’s sidelong glare dominates the mood of the work more than a supposed leprosy might. Volet paints the groups’ general stilled acquiesce. What else can they do, being stilled? Religious arraignment presides for this second. Eroticism ensues in Buñuel’s version. Volet sustains our suspense.

Volet’s table is spare. Dishes are empty. People sitting left of the picture plane past the nun’s scrutiny are undersized, their influence on the event diminished. A wide unlit rear fireplace is a grotto of unidentified depths. The work is shrouded in poverty. Volet paints the impoverished mind, where proof is required to trust. Depleted spirits hungry for purpose are preoccupied with the provocation of an outsiders’ probing. The nun’s garb tone equals the others. She too is suppliant, although presumptuous of the import of her role. We question the arbiter’s questioning. Sumptuous black blocks, withholds information, starves us while testing our patience like anyone at the table.

Christian Metz’s 1978 publication, “Essais sur la Signification au Cinéma “.Vol. 2, p. 23 writes that the cinematic screen masks and frames, conceals and structures, limiting the viewer’s understanding of the image(s) to direct attention, construct tension. We cannot know the whole story Volet paints, only what he chooses to show us. Volet feeds us dramatic irony to appease our need for narration, our discomfort and willing separation from the implausibility of poverty. Who would willingly condescend to sit with pariahs or associate with the needy? What is their need to transgress boundaries of propriety?

The banquet is Volet’s offering of intrigue. He invites us to the banquet because we are the disadvantaged, the leper, consuming insignificance, one of the indistinguishable at an empty table. We need explanation to be confident in our separateness from social injustice. In Beggars Banquet we can see the people are out of our time, out of our experience, and can attribute the indefinite or unfamiliar to otherness, black and white thinking. We participate in a banquet of existential apartness when we are strangers to the ambiguous, reject vagueness as unreal, segregate ourselves from others’ chronicles. We take comfort in our separation from the outmoded or obsolete scene we can assert is strange - to most of us - relative to the comforts afforded by Western Civilization, unknowable, a poor table. We are the unrequited guest at Beggars Banquet. Our requisite is Volet’s silent subterfuge.

Publications originating from the Paris Collège de 'Pataphysique are collectively calledViridis Candela ("green candle") [2]. Two of Volet’s works have a green candle glow (Beggars Banquet stars Viridiana, provides another green reference), an impossible luminous intensity that might be seen to oppose the quaint as a sepia toned film still might conjoin to an idealized nostalgia, a protanopia monochrome articulating the past in the presence of a cycling Alfred Jarry, rex inutilis (useless king) capitulated in a Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry where Volet captures and surrenders to the king of incredulity. Volet yields to Jarry’s cyclist soul requiring the joy and antics possible on that vehicle that propelled the instigator of a “science of imaginary solutions” [3] (pataphysics). Volet’s painted treatment of the solitary cyclist, Jarry shows the image copied from the with shut eyes, turning a historic author into a blind moving time traveller, epitomized by the artist’s explorer machinations as painted egress.

![clip_image006[1] clip_image006[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhuIuflE8nY9OgwlmE922GR1REWsowfLwStj3JCQdJwTTB_wrmb4L5geqo3STk8D9DxZIifFet4s6WXsi-30bpg5Q2k38dATBmi0Gg96R0K0ru3GIvppV-A900bVF52WxJ44i9V_g/?imgmax=800)

Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas – 4 x 5’

![clip_image008[1] clip_image008[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgBwsd8c5vGH_coGkiMnyzxShptid8Za_qAzrCXIXwhAtS2cEXJP02r84BPkzKpU0loX5scepv-KgNK01rCsdsu-ZvbqrDX-KMS05Jl90U9Olk_8_ewc2Mqs7rKtKWpq1nDIfIRvA/?imgmax=800)

Erik Volet - MOCL Gallery installation. June 2014

![clip_image010[1] clip_image010[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiFDfvu8F5nUx-_ij4o0DGNBtyL5YaHvfq3ACJfZkQFAxB5cwhQOoSN25AwqdS3bTRiO2Gb8F2OLJZDhpr7QLsERE_q6FFxI4k29bkNhDjKD9MywgFlX-psvATuNxoaz9A2FULG-w/?imgmax=800)

Teetotaler in the Saloon - Erik Volet - Oil on Canvas – 3 x 4’

Although this work is definitive without the mushing, pulpy sentimentality of either e.g. a Dorothea Tanning transience, or a Marc Chagall floating figure sensibility , Teetotaler in the Saloon evokes thoughts of both presentations. We find corporeal incongruity to be normalcy. A Pieter Brueghel the elder multiplex of scenes, with a van Gogh / Issac Abrams colour palate, Volet’s opposing ceruleans and oranges strike the eye with the compunction of a bright but conflicting conscience one wishes one could leave in a public place to be stolen but cannot forgetten. The gangly tea drinker is suspended in disbelief with what surrounds him, unbearable legs extending from the round central tabletop. Allusions to this figure is echoed with a floor inclined body and a fellow entering a yellow oval in the back (ideal future sunniness), sauntering to a peeking cast behind the red drape. Temporal extensions are saloon dwellers in front of a red curtain, a staging of saloon/cafe culture. These are social tests for the solo hatted studier of mores in several poses. Teetotaler is every man, everywhere. Teetotaler is anyone’s mind rejoining coloured contradictions.

André Breton spoke about Meret Oppenheim’s ‘use values’ redefined, the rational concerning her work to generate disorientation, impose surreal functions with objects, noted by Josef Helfenstein in “Against the intolerability of fame: Meret Oppenheim and Surrealism” in ‘‘Beyond the Teacup,’’ p. 24, ed. by Jacqueline Burkhardt and Bice Curiger (New York: Independent Curators Incorporated, 1996), p 29. Volet’s teetotaller is fuzzy, tea an obfuscation device, the mental confusion of the tea drinker. He interprets isolation in social settings that might be seen through a quote attributed to Rat Pack member, Dean Martin, “King of Cool” (American actor and singer. 1917-1995) know for his extensive alcohol consumption, “I'd hate to be a teetotaler. Imagine getting up in the morning and knowing that's as good as you're going to feel all day.”

Volet’s teetotaler looks sober, bearing the vesture of distraction and mystification, the result of abstemiousness. The character absents himself from communal interaction, judicious, perhaps accepting what Alfred Jarry wrote in La Revue Blanche, 1897, "It is because the public are a mass—inert, obtuse, and passive—that they need to be shaken up from time to time so that we can tell from their bear-like grunts where they are—and also where they stand. They are pretty harmless, in spite of their numbers, because they are fighting against intelligence." Volet’s main character’s legs describe a person that does not easily withstand anything or cannot assert his will. This teetotaler partakes in his populated ruminations instead, an impalpable place.

![clip_image012[1] clip_image012[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhIC82Zd8b7l3-_f3k2a9ouhuj01QK8vKAmnp7UBJAKauyDMl4wV5JVAKBqSU4o-w3PutTd4tjtmw_ZldEFfoM3O-wiZk3YvKtD8TVtAAgFHup3ltW1kFomMufylM4d4RW2EzrmfA/?imgmax=800)

Erik Volet - MOCL Gallery installation

We move in the direction of Time and at the same speed, being ourselves part of the Present. If we could remain immobile absolute Space while Time elapses, if we could lock our selves inside a Machine that isolates us from Time (except for the small and normal "speed of duration" that will stay with us because of inertia), all future and past instants could be explored successively, just as the stationary spectator of a panorama has the illusion of a swift voyage through a series of landscapes. (We shall demonstrate later that, as seen from the Machine, the Past lies beyond the Future.)

(...)

Duration is the transformation of a succession into a reversion.

In other words:

THE BECOMING OF A MEMORY.

~ Alfred Jarry. “How to Construct a Time Machine”. Selected Works of Alfred Jarry, edited by Roger Shattuck & Simon Watson Taylor, New York, Grove Press (1965, 1980)

Volet’s exhibition evokes the divergent Alfred Jarry’s 1899 instructions, “How to Construct a Time Machine” (tr. by Roger Shattuck). Volet gathers us in the MOCL time capsule so we may contemplate the future and past, photographic evidence transpires through Volet’s painted evaluations of time and space, a simultaneous opportunity to investigate contradictory lives and confirm what may lay beyond his panoramas.

Through his populated landscapes we understand how Volet penetrates and eludes denouncement of devout palaver by dramatically enlarging reproductions of varied loci. He extends images to enlarge space, preventing insular thinking, frustrate inertia, complacency. Volet’s need to expand historical imagery renders and surmounts cultural ambivalence with his large works, mainly monochrome to simplify allowing commensurability. Volet realizes concurrent elasticity and unyielding phenomena. He paints an intense concentration of impossible human viscosity, thick sticky human consciousness, the banal, the poetic. Volet has succeeded in converting his reevaluations into cogent, illusory resolutions, striking transformations. Obdurate memory becomes Volet’s rejoinder. Kings would would proffer a toast.

[1]http://jafi.org/JewishAgency/English/Jewish+Education/Compelling+Content/Jewish+Time/Festivals+and+Memorial+Days/Purim/PUR+PURIM+The+Source+and+the+Meaning+of+the+Term.htm

[2] Hugill, Andrew (2012). 'Pataphysics: A useless guide. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01779-4

[3] http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/public/article1246470.ece

Thursday, May 22, 2014

Erik Volet

Scene from the Yiddish Theatre & Other Paintings

1-15 June 2014

Erik Volet - Exhibit-v Interview

Ministry of Casual Living

819 Fort Street

Victoria BC

Review by Debora Alanna

The theater, bringing impersonal masks to life, is only for those who are virile enough to create new life: either as a conflict of passions subtler than those we already know, or as a complete new character.

~ Alfred Jarry (1873-1907). “Twelve Theatrical Topics “, Topic 4, in Dossiers Caneles du college de pataphysique, no 5. (Paris, 1960: rep in Selected Works of Alfred Jarry, ed. by Roger Shattuck and Simon Watson Taylor, 1965).

Erik Volet entitled his current exhibition at the Ministry of Casual Living (MOCL), Scene from the Yiddish Theatre & Other Paintings. Large paintings are images gleaned from historical photographs. Yiddish culture, specifically a Purim speil (play) performed in a home is titled Scene from the Yiddish Theatre. A communal meal illustrates uncertainty about being bound to classification that religion, disease and poverty involves appears inBeggars Banquet. Alfred Jarry upon his velo in Alfortville is Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry and Jarry carrying a boat with another Volet titled, Jarry Carring the Skiff. Included in this exhibition are painting investigations diverging from the Yiddish and Jarry contexts, distinct cultural pondering also from photographs or photographic references - Stolen Journey and Khmer Dancers. An oblique reference to “Portrait of Fernando Pessoa” by Jose de Almanda-Negreiros, 1954 is transformed into Volet’sTeetotaller in the Saloon.

Learned, vivid essays by John Luna and Astrid Wright distinguish Volet’s exhibition catalogue.

![clip_image002[1] clip_image002[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH9_kMwsNOCmLdOqTbW0bDo1_VIJ_DaTPni-dwWP1VzvvD226exaNoT5TIHvbx3tpT_1vBwotB9IEJSouyrBlQaWiTbf2d9U2LOHcDRWtHoiJ4xdfblROcM7k8UZBFJTWoR-AZRg/?imgmax=800)

Scene from the Yiddish Theatre - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas - 4 x 6’

Borrowing from Jarry’s Topic 4 (above), Volet allows import and disquiet of his personal response to the outwardly impersonal presence within photographic masks. Masking or obfuscation of what may have been personal for the people within the photos seen in books and articles as uncertain subjects that evoke narrative descriptions complementing texts cultivate a performance with Volet’s use and transformation of these images. He involves us in impalpable conflicts between diligence and enthusiasm, desire and idealised devotion. Volet creates new portrayals, portals into and from historical, cultural reverence of a detained, ponderous existence.

Enlarged venerated images impose because realms of significance extend beyond an original photograph or a photo on a printed page, outside the scope of appropriation and reproduction. The work, Scene from the Yiddish Theatre becomes an entrancing introduction from which to view the entire show. The pretext for comic dramatization by children during the Purim festival, Purimshpiln, allows a vehicle to play out the repercussions of chance and or coincidence (Pur means lottery [1] – an astrological forecast indicating when Jews were most vulnerable 2500 years ago in Persia) is a means to reveal hidden natures and true characters as described in the Book of Ester. Hiding one’s true nature, our essential character, still plagues the human condition and the guise of acting out intention through dramatic play available to children seems enviable. Volet questions fundamental import, what plays out, in when drawn existing within the tragic-comic human condition.

A weakened adult audience is sullen to the left of the animated players that are greater than the sideliners. Volet paints a monochrome that evokes an intention to cultivate mirth and meaning from whatever is at hand, a Les Arts Incohérents’ saucy satire. To be an audience alone is a grave and improbable, impoverished existence. Ingenuousness is lively and teases out what can be impossible to discover without the lark.

![clip_image004[1] clip_image004[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiXaug8ZWBeNbkTxO2dBZ4N8xe6n7NXTojJ7yvIjRv3w3Lxexx8UEExaL91hh5f3-z9AlYxTKQCWRYuPGqG07ZdUPLMRezio2NRbqWZKVomQDh7z7X96qvyGq9USCxVm0yr6iCvAg/?imgmax=800)

Beggars Banquet - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas – 4 x 5’

And when i search a faceless crowd

a swirling mass of gray and

black and white

they don't look real to me

in fact, they look so strange

~ Chorus from “Salt Of The Earth”. Rolling Stones. Album: Beggars Banquet - 1968

Volet continues to wield and vanquish, to sport and supplant histories with grey scales.Beggars Banquet is saturated with shadows using severe black and testaments of grey, frightening white, a social chiaroscuro shows a meagre table, set for seemingly rustic if not rural, diners, possibly a group of pre - 20th century moujik. The close diagonal table corner points at us, inviting us to join the motley group. A distant male figure, far right watches our approach. Volet weighs qualities of humanity.

Utilizing a still from Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana, Volet chose the moment where Viridiana, a novice nun attempts charity before her eventual sexual entanglements in the movie. The image is not a banquet of bliss availed by religious order but the abundant dearth of religion. Volet’s use of the Buñuel sardonic wink at charity’s anarchy includes us, his audience in the caper.

The front right featured guest at the Beggars Banquet is a leper being assessed by religious order. His arm held to ascertain the degree of his leprosy, a nun examines his appendage, presumably the man’s ability to eat, degree of degeneration. The diners pause their repast. The nun’s sidelong glare dominates the mood of the work more than a supposed leprosy might. Volet paints the groups’ general stilled acquiesce. What else can they do, being stilled? Religious arraignment presides for this second. Eroticism ensues in Buñuel’s version. Volet sustains our suspense.

Volet’s table is spare. Dishes are empty. People sitting left of the picture plane past the nun’s scrutiny are undersized, their influence on the event diminished. A wide unlit rear fireplace is a grotto of unidentified depths. The work is shrouded in poverty. Volet paints the impoverished mind, where proof is required to trust. Depleted spirits hungry for purpose are preoccupied with the provocation of an outsiders’ probing. The nun’s garb tone equals the others. She too is suppliant, although presumptuous of the import of her role. We question the arbiter’s questioning. Sumptuous black blocks, withholds information, starves us while testing our patience like anyone at the table.

Christian Metz’s 1978 publication, “Essais sur la Signification au Cinéma “.Vol. 2, p. 23 writes that the cinematic screen masks and frames, conceals and structures, limiting the viewer’s understanding of the image(s) to direct attention, construct tension. We cannot know the whole story Volet paints, only what he chooses to show us. Volet feeds us dramatic irony to appease our need for narration, our discomfort and willing separation from the implausibility of poverty. Who would willingly condescend to sit with pariahs or associate with the needy? What is their need to transgress boundaries of propriety?

The banquet is Volet’s offering of intrigue. He invites us to the banquet because we are the disadvantaged, the leper, consuming insignificance, one of the indistinguishable at an empty table. We need explanation to be confident in our separateness from social injustice. In Beggars Banquet we can see the people are out of our time, out of our experience, and can attribute the indefinite or unfamiliar to otherness, black and white thinking. We participate in a banquet of existential apartness when we are strangers to the ambiguous, reject vagueness as unreal, segregate ourselves from others’ chronicles. We take comfort in our separation from the outmoded or obsolete scene we can assert is strange - to most of us - relative to the comforts afforded by Western Civilization, unknowable, a poor table. We are the unrequited guest at Beggars Banquet. Our requisite is Volet’s silent subterfuge.

Publications originating from the Paris Collège de 'Pataphysique are collectively calledViridis Candela ("green candle") [2]. Two of Volet’s works have a green candle glow (Beggars Banquet stars Viridiana, provides another green reference), an impossible luminous intensity that might be seen to oppose the quaint as a sepia toned film still might conjoin to an idealized nostalgia, a protanopia monochrome articulating the past in the presence of a cycling Alfred Jarry, rex inutilis (useless king) capitulated in a Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry where Volet captures and surrenders to the king of incredulity. Volet yields to Jarry’s cyclist soul requiring the joy and antics possible on that vehicle that propelled the instigator of a “science of imaginary solutions” [3] (pataphysics). Volet’s painted treatment of the solitary cyclist, Jarry shows the image copied from the with shut eyes, turning a historic author into a blind moving time traveller, epitomized by the artist’s explorer machinations as painted egress.

![clip_image006[1] clip_image006[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhuIuflE8nY9OgwlmE922GR1REWsowfLwStj3JCQdJwTTB_wrmb4L5geqo3STk8D9DxZIifFet4s6WXsi-30bpg5Q2k38dATBmi0Gg96R0K0ru3GIvppV-A900bVF52WxJ44i9V_g/?imgmax=800)

Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas – 4 x 5’

![clip_image008[1] clip_image008[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgBwsd8c5vGH_coGkiMnyzxShptid8Za_qAzrCXIXwhAtS2cEXJP02r84BPkzKpU0loX5scepv-KgNK01rCsdsu-ZvbqrDX-KMS05Jl90U9Olk_8_ewc2Mqs7rKtKWpq1nDIfIRvA/?imgmax=800)

Erik Volet - MOCL Gallery installation. June 2014

![clip_image010[1] clip_image010[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiFDfvu8F5nUx-_ij4o0DGNBtyL5YaHvfq3ACJfZkQFAxB5cwhQOoSN25AwqdS3bTRiO2Gb8F2OLJZDhpr7QLsERE_q6FFxI4k29bkNhDjKD9MywgFlX-psvATuNxoaz9A2FULG-w/?imgmax=800)

Teetotaler in the Saloon - Erik Volet - Oil on Canvas – 3 x 4’

Although this work is definitive without the mushing, pulpy sentimentality of either e.g. a Dorothea Tanning transience, or a Marc Chagall floating figure sensibility , Teetotaler in the Saloon evokes thoughts of both presentations. We find corporeal incongruity to be normalcy. A Pieter Brueghel the elder multiplex of scenes, with a van Gogh / Issac Abrams colour palate, Volet’s opposing ceruleans and oranges strike the eye with the compunction of a bright but conflicting conscience one wishes one could leave in a public place to be stolen but cannot forgetten. The gangly tea drinker is suspended in disbelief with what surrounds him, unbearable legs extending from the round central tabletop. Allusions to this figure is echoed with a floor inclined body and a fellow entering a yellow oval in the back (ideal future sunniness), sauntering to a peeking cast behind the red drape. Temporal extensions are saloon dwellers in front of a red curtain, a staging of saloon/cafe culture. These are social tests for the solo hatted studier of mores in several poses. Teetotaler is every man, everywhere. Teetotaler is anyone’s mind rejoining coloured contradictions.

André Breton spoke about Meret Oppenheim’s ‘use values’ redefined, the rational concerning her work to generate disorientation, impose surreal functions with objects, noted by Josef Helfenstein in “Against the intolerability of fame: Meret Oppenheim and Surrealism” in ‘‘Beyond the Teacup,’’ p. 24, ed. by Jacqueline Burkhardt and Bice Curiger (New York: Independent Curators Incorporated, 1996), p 29. Volet’s teetotaller is fuzzy, tea an obfuscation device, the mental confusion of the tea drinker. He interprets isolation in social settings that might be seen through a quote attributed to Rat Pack member, Dean Martin, “King of Cool” (American actor and singer. 1917-1995) know for his extensive alcohol consumption, “I'd hate to be a teetotaler. Imagine getting up in the morning and knowing that's as good as you're going to feel all day.”

Volet’s teetotaler looks sober, bearing the vesture of distraction and mystification, the result of abstemiousness. The character absents himself from communal interaction, judicious, perhaps accepting what Alfred Jarry wrote in La Revue Blanche, 1897, "It is because the public are a mass—inert, obtuse, and passive—that they need to be shaken up from time to time so that we can tell from their bear-like grunts where they are—and also where they stand. They are pretty harmless, in spite of their numbers, because they are fighting against intelligence." Volet’s main character’s legs describe a person that does not easily withstand anything or cannot assert his will. This teetotaler partakes in his populated ruminations instead, an impalpable place.

![clip_image012[1] clip_image012[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhIC82Zd8b7l3-_f3k2a9ouhuj01QK8vKAmnp7UBJAKauyDMl4wV5JVAKBqSU4o-w3PutTd4tjtmw_ZldEFfoM3O-wiZk3YvKtD8TVtAAgFHup3ltW1kFomMufylM4d4RW2EzrmfA/?imgmax=800)

Erik Volet - MOCL Gallery installation

We move in the direction of Time and at the same speed, being ourselves part of the Present. If we could remain immobile absolute Space while Time elapses, if we could lock our selves inside a Machine that isolates us from Time (except for the small and normal "speed of duration" that will stay with us because of inertia), all future and past instants could be explored successively, just as the stationary spectator of a panorama has the illusion of a swift voyage through a series of landscapes. (We shall demonstrate later that, as seen from the Machine, the Past lies beyond the Future.)

(...)

Duration is the transformation of a succession into a reversion.

In other words:

THE BECOMING OF A MEMORY.

~ Alfred Jarry. “How to Construct a Time Machine”. Selected Works of Alfred Jarry, edited by Roger Shattuck & Simon Watson Taylor, New York, Grove Press (1965, 1980)

Volet’s exhibition evokes the divergent Alfred Jarry’s 1899 instructions, “How to Construct a Time Machine” (tr. by Roger Shattuck). Volet gathers us in the MOCL time capsule so we may contemplate the future and past, photographic evidence transpires through Volet’s painted evaluations of time and space, a simultaneous opportunity to investigate contradictory lives and confirm what may lay beyond his panoramas.

Through his populated landscapes we understand how Volet penetrates and eludes denouncement of devout palaver by dramatically enlarging reproductions of varied loci. He extends images to enlarge space, preventing insular thinking, frustrate inertia, complacency. Volet’s need to expand historical imagery renders and surmounts cultural ambivalence with his large works, mainly monochrome to simplify allowing commensurability. Volet realizes concurrent elasticity and unyielding phenomena. He paints an intense concentration of impossible human viscosity, thick sticky human consciousness, the banal, the poetic. Volet has succeeded in converting his reevaluations into cogent, illusory resolutions, striking transformations. Obdurate memory becomes Volet’s rejoinder. Kings would would proffer a toast.

[1]http://jafi.org/JewishAgency/English/Jewish+Education/Compelling+Content/Jewish+Time/Festivals+and+Memorial+Days/Purim/PUR+PURIM+The+Source+and+the+Meaning+of+the+Term.htm

[2] Hugill, Andrew (2012). 'Pataphysics: A useless guide. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01779-4

[3] http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/public/article1246470.ece

Scene from the Yiddish Theatre & Other Paintings

1-15 June 2014

Erik Volet - Exhibit-v Interview

Ministry of Casual Living

819 Fort Street

Victoria BC

Review by Debora Alanna

The theater, bringing impersonal masks to life, is only for those who are virile enough to create new life: either as a conflict of passions subtler than those we already know, or as a complete new character.

~ Alfred Jarry (1873-1907). “Twelve Theatrical Topics “, Topic 4, in Dossiers Caneles du college de pataphysique, no 5. (Paris, 1960: rep in Selected Works of Alfred Jarry, ed. by Roger Shattuck and Simon Watson Taylor, 1965).

Erik Volet entitled his current exhibition at the Ministry of Casual Living (MOCL), Scene from the Yiddish Theatre & Other Paintings. Large paintings are images gleaned from historical photographs. Yiddish culture, specifically a Purim speil (play) performed in a home is titled Scene from the Yiddish Theatre. A communal meal illustrates uncertainty about being bound to classification that religion, disease and poverty involves appears inBeggars Banquet. Alfred Jarry upon his velo in Alfortville is Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry and Jarry carrying a boat with another Volet titled, Jarry Carring the Skiff. Included in this exhibition are painting investigations diverging from the Yiddish and Jarry contexts, distinct cultural pondering also from photographs or photographic references - Stolen Journey and Khmer Dancers. An oblique reference to “Portrait of Fernando Pessoa” by Jose de Almanda-Negreiros, 1954 is transformed into Volet’sTeetotaller in the Saloon.

Learned, vivid essays by John Luna and Astrid Wright distinguish Volet’s exhibition catalogue.

![clip_image002[1] clip_image002[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH9_kMwsNOCmLdOqTbW0bDo1_VIJ_DaTPni-dwWP1VzvvD226exaNoT5TIHvbx3tpT_1vBwotB9IEJSouyrBlQaWiTbf2d9U2LOHcDRWtHoiJ4xdfblROcM7k8UZBFJTWoR-AZRg/?imgmax=800)

Scene from the Yiddish Theatre - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas - 4 x 6’

Borrowing from Jarry’s Topic 4 (above), Volet allows import and disquiet of his personal response to the outwardly impersonal presence within photographic masks. Masking or obfuscation of what may have been personal for the people within the photos seen in books and articles as uncertain subjects that evoke narrative descriptions complementing texts cultivate a performance with Volet’s use and transformation of these images. He involves us in impalpable conflicts between diligence and enthusiasm, desire and idealised devotion. Volet creates new portrayals, portals into and from historical, cultural reverence of a detained, ponderous existence.

Enlarged venerated images impose because realms of significance extend beyond an original photograph or a photo on a printed page, outside the scope of appropriation and reproduction. The work, Scene from the Yiddish Theatre becomes an entrancing introduction from which to view the entire show. The pretext for comic dramatization by children during the Purim festival, Purimshpiln, allows a vehicle to play out the repercussions of chance and or coincidence (Pur means lottery [1] – an astrological forecast indicating when Jews were most vulnerable 2500 years ago in Persia) is a means to reveal hidden natures and true characters as described in the Book of Ester. Hiding one’s true nature, our essential character, still plagues the human condition and the guise of acting out intention through dramatic play available to children seems enviable. Volet questions fundamental import, what plays out, in when drawn existing within the tragic-comic human condition.

A weakened adult audience is sullen to the left of the animated players that are greater than the sideliners. Volet paints a monochrome that evokes an intention to cultivate mirth and meaning from whatever is at hand, a Les Arts Incohérents’ saucy satire. To be an audience alone is a grave and improbable, impoverished existence. Ingenuousness is lively and teases out what can be impossible to discover without the lark.

![clip_image004[1] clip_image004[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiXaug8ZWBeNbkTxO2dBZ4N8xe6n7NXTojJ7yvIjRv3w3Lxexx8UEExaL91hh5f3-z9AlYxTKQCWRYuPGqG07ZdUPLMRezio2NRbqWZKVomQDh7z7X96qvyGq9USCxVm0yr6iCvAg/?imgmax=800)

Beggars Banquet - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas – 4 x 5’

And when i search a faceless crowd

a swirling mass of gray and

black and white

they don't look real to me

in fact, they look so strange

~ Chorus from “Salt Of The Earth”. Rolling Stones. Album: Beggars Banquet - 1968

Volet continues to wield and vanquish, to sport and supplant histories with grey scales.Beggars Banquet is saturated with shadows using severe black and testaments of grey, frightening white, a social chiaroscuro shows a meagre table, set for seemingly rustic if not rural, diners, possibly a group of pre - 20th century moujik. The close diagonal table corner points at us, inviting us to join the motley group. A distant male figure, far right watches our approach. Volet weighs qualities of humanity.

Utilizing a still from Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana, Volet chose the moment where Viridiana, a novice nun attempts charity before her eventual sexual entanglements in the movie. The image is not a banquet of bliss availed by religious order but the abundant dearth of religion. Volet’s use of the Buñuel sardonic wink at charity’s anarchy includes us, his audience in the caper.

The front right featured guest at the Beggars Banquet is a leper being assessed by religious order. His arm held to ascertain the degree of his leprosy, a nun examines his appendage, presumably the man’s ability to eat, degree of degeneration. The diners pause their repast. The nun’s sidelong glare dominates the mood of the work more than a supposed leprosy might. Volet paints the groups’ general stilled acquiesce. What else can they do, being stilled? Religious arraignment presides for this second. Eroticism ensues in Buñuel’s version. Volet sustains our suspense.

Volet’s table is spare. Dishes are empty. People sitting left of the picture plane past the nun’s scrutiny are undersized, their influence on the event diminished. A wide unlit rear fireplace is a grotto of unidentified depths. The work is shrouded in poverty. Volet paints the impoverished mind, where proof is required to trust. Depleted spirits hungry for purpose are preoccupied with the provocation of an outsiders’ probing. The nun’s garb tone equals the others. She too is suppliant, although presumptuous of the import of her role. We question the arbiter’s questioning. Sumptuous black blocks, withholds information, starves us while testing our patience like anyone at the table.

Christian Metz’s 1978 publication, “Essais sur la Signification au Cinéma “.Vol. 2, p. 23 writes that the cinematic screen masks and frames, conceals and structures, limiting the viewer’s understanding of the image(s) to direct attention, construct tension. We cannot know the whole story Volet paints, only what he chooses to show us. Volet feeds us dramatic irony to appease our need for narration, our discomfort and willing separation from the implausibility of poverty. Who would willingly condescend to sit with pariahs or associate with the needy? What is their need to transgress boundaries of propriety?

The banquet is Volet’s offering of intrigue. He invites us to the banquet because we are the disadvantaged, the leper, consuming insignificance, one of the indistinguishable at an empty table. We need explanation to be confident in our separateness from social injustice. In Beggars Banquet we can see the people are out of our time, out of our experience, and can attribute the indefinite or unfamiliar to otherness, black and white thinking. We participate in a banquet of existential apartness when we are strangers to the ambiguous, reject vagueness as unreal, segregate ourselves from others’ chronicles. We take comfort in our separation from the outmoded or obsolete scene we can assert is strange - to most of us - relative to the comforts afforded by Western Civilization, unknowable, a poor table. We are the unrequited guest at Beggars Banquet. Our requisite is Volet’s silent subterfuge.

Publications originating from the Paris Collège de 'Pataphysique are collectively calledViridis Candela ("green candle") [2]. Two of Volet’s works have a green candle glow (Beggars Banquet stars Viridiana, provides another green reference), an impossible luminous intensity that might be seen to oppose the quaint as a sepia toned film still might conjoin to an idealized nostalgia, a protanopia monochrome articulating the past in the presence of a cycling Alfred Jarry, rex inutilis (useless king) capitulated in a Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry where Volet captures and surrenders to the king of incredulity. Volet yields to Jarry’s cyclist soul requiring the joy and antics possible on that vehicle that propelled the instigator of a “science of imaginary solutions” [3] (pataphysics). Volet’s painted treatment of the solitary cyclist, Jarry shows the image copied from the with shut eyes, turning a historic author into a blind moving time traveller, epitomized by the artist’s explorer machinations as painted egress.

![clip_image006[1] clip_image006[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhuIuflE8nY9OgwlmE922GR1REWsowfLwStj3JCQdJwTTB_wrmb4L5geqo3STk8D9DxZIifFet4s6WXsi-30bpg5Q2k38dATBmi0Gg96R0K0ru3GIvppV-A900bVF52WxJ44i9V_g/?imgmax=800)

Le Cyclist de Monmatre: Portrait of Alfred Jarry - Erik Volet - Oil on canvas – 4 x 5’

![clip_image008[1] clip_image008[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgBwsd8c5vGH_coGkiMnyzxShptid8Za_qAzrCXIXwhAtS2cEXJP02r84BPkzKpU0loX5scepv-KgNK01rCsdsu-ZvbqrDX-KMS05Jl90U9Olk_8_ewc2Mqs7rKtKWpq1nDIfIRvA/?imgmax=800)

Erik Volet - MOCL Gallery installation. June 2014

![clip_image010[1] clip_image010[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiFDfvu8F5nUx-_ij4o0DGNBtyL5YaHvfq3ACJfZkQFAxB5cwhQOoSN25AwqdS3bTRiO2Gb8F2OLJZDhpr7QLsERE_q6FFxI4k29bkNhDjKD9MywgFlX-psvATuNxoaz9A2FULG-w/?imgmax=800)

Teetotaler in the Saloon - Erik Volet - Oil on Canvas – 3 x 4’

Although this work is definitive without the mushing, pulpy sentimentality of either e.g. a Dorothea Tanning transience, or a Marc Chagall floating figure sensibility , Teetotaler in the Saloon evokes thoughts of both presentations. We find corporeal incongruity to be normalcy. A Pieter Brueghel the elder multiplex of scenes, with a van Gogh / Issac Abrams colour palate, Volet’s opposing ceruleans and oranges strike the eye with the compunction of a bright but conflicting conscience one wishes one could leave in a public place to be stolen but cannot forgetten. The gangly tea drinker is suspended in disbelief with what surrounds him, unbearable legs extending from the round central tabletop. Allusions to this figure is echoed with a floor inclined body and a fellow entering a yellow oval in the back (ideal future sunniness), sauntering to a peeking cast behind the red drape. Temporal extensions are saloon dwellers in front of a red curtain, a staging of saloon/cafe culture. These are social tests for the solo hatted studier of mores in several poses. Teetotaler is every man, everywhere. Teetotaler is anyone’s mind rejoining coloured contradictions.

André Breton spoke about Meret Oppenheim’s ‘use values’ redefined, the rational concerning her work to generate disorientation, impose surreal functions with objects, noted by Josef Helfenstein in “Against the intolerability of fame: Meret Oppenheim and Surrealism” in ‘‘Beyond the Teacup,’’ p. 24, ed. by Jacqueline Burkhardt and Bice Curiger (New York: Independent Curators Incorporated, 1996), p 29. Volet’s teetotaller is fuzzy, tea an obfuscation device, the mental confusion of the tea drinker. He interprets isolation in social settings that might be seen through a quote attributed to Rat Pack member, Dean Martin, “King of Cool” (American actor and singer. 1917-1995) know for his extensive alcohol consumption, “I'd hate to be a teetotaler. Imagine getting up in the morning and knowing that's as good as you're going to feel all day.”

Volet’s teetotaler looks sober, bearing the vesture of distraction and mystification, the result of abstemiousness. The character absents himself from communal interaction, judicious, perhaps accepting what Alfred Jarry wrote in La Revue Blanche, 1897, "It is because the public are a mass—inert, obtuse, and passive—that they need to be shaken up from time to time so that we can tell from their bear-like grunts where they are—and also where they stand. They are pretty harmless, in spite of their numbers, because they are fighting against intelligence." Volet’s main character’s legs describe a person that does not easily withstand anything or cannot assert his will. This teetotaler partakes in his populated ruminations instead, an impalpable place.

![clip_image012[1] clip_image012[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhIC82Zd8b7l3-_f3k2a9ouhuj01QK8vKAmnp7UBJAKauyDMl4wV5JVAKBqSU4o-w3PutTd4tjtmw_ZldEFfoM3O-wiZk3YvKtD8TVtAAgFHup3ltW1kFomMufylM4d4RW2EzrmfA/?imgmax=800)

Erik Volet - MOCL Gallery installation

We move in the direction of Time and at the same speed, being ourselves part of the Present. If we could remain immobile absolute Space while Time elapses, if we could lock our selves inside a Machine that isolates us from Time (except for the small and normal "speed of duration" that will stay with us because of inertia), all future and past instants could be explored successively, just as the stationary spectator of a panorama has the illusion of a swift voyage through a series of landscapes. (We shall demonstrate later that, as seen from the Machine, the Past lies beyond the Future.)

(...)

Duration is the transformation of a succession into a reversion.

In other words:

THE BECOMING OF A MEMORY.

~ Alfred Jarry. “How to Construct a Time Machine”. Selected Works of Alfred Jarry, edited by Roger Shattuck & Simon Watson Taylor, New York, Grove Press (1965, 1980)

Volet’s exhibition evokes the divergent Alfred Jarry’s 1899 instructions, “How to Construct a Time Machine” (tr. by Roger Shattuck). Volet gathers us in the MOCL time capsule so we may contemplate the future and past, photographic evidence transpires through Volet’s painted evaluations of time and space, a simultaneous opportunity to investigate contradictory lives and confirm what may lay beyond his panoramas.

Through his populated landscapes we understand how Volet penetrates and eludes denouncement of devout palaver by dramatically enlarging reproductions of varied loci. He extends images to enlarge space, preventing insular thinking, frustrate inertia, complacency. Volet’s need to expand historical imagery renders and surmounts cultural ambivalence with his large works, mainly monochrome to simplify allowing commensurability. Volet realizes concurrent elasticity and unyielding phenomena. He paints an intense concentration of impossible human viscosity, thick sticky human consciousness, the banal, the poetic. Volet has succeeded in converting his reevaluations into cogent, illusory resolutions, striking transformations. Obdurate memory becomes Volet’s rejoinder. Kings would would proffer a toast.

[1]http://jafi.org/JewishAgency/English/Jewish+Education/Compelling+Content/Jewish+Time/Festivals+and+Memorial+Days/Purim/PUR+PURIM+The+Source+and+the+Meaning+of+the+Term.htm