Tuesday, September 20, 2011

Philip Willey “Provincial Life “ by Debora Alanna

Unlucky the hero born

In this province of the stuck record

From: “The Times are Tidy” by Sylvia Plath

The Province of the Saved

Should be the Art

From: “The Province of the Saved” by Emily Dickenson

“It is in society that people normally acquire their memories. It is also in society that they recall, recognize, and localize their memories” [1]

Provincial Life is this year’s oeuvre for Philip Willey. An unassuming exposition, this show contrasts existent historical references with the past. He introduces themes from a documented archive, which brings the visual commentary to the forefront and allows drawn and painted portraits intermingling local backdrops to propose a reassessment of history’s recollection that may intensify present processing.

Willey plays with Hannah Maynard’s image, a photographer who challenged photographic space in 1860’s Victoria. She cycles steadily with brandish strokes of lively colour before the Spiral Café, and stopping her bike while merrily collaged, she looks at a photographed excerpt of a John Luna work in bold address of present and future provincialism, a readable argument to thwart any naysayer. An inspired entity defying convention, Maynard provides Willey with a muse.

Soonghees village life with steadfast, carved canoes shored at the current Fort Street waterfront reveals the Blue Bridge in the distance, and in another work, paddlers confront the soon to be bridge or row past a little ferry. Gallantly pointing bows, Willey points to future violations, a portent of life we have overpowered, and the presage of ruin eminent with disregard of what is valuable about our cultural mediums. A biting contrast of whalers next to whale watchers (Moral Dilemma), he drives the lost life forward. Willey postulates the affect of cultural influence. His works are deftly drawn and painted with a wash of colour deferentially shaping nostalgia, both for the past lives lived through our engineered landmarks, soon redefining our mores.

A bike rider pulling a child in a covered yellow rain cart, a symbol of a contemporary urban professionals looks at the viewer with Fort Victoria as their neighbourhood, challenging our outlook with their oblivion. In another work, a horse drawn cart is poised in Bastion square providing imagery to compare past and present scenarios of provincial life. Capable of precise draughtsmanship, when Willey is looser with his lines (Bob’s Your Uncle), he shows how we fumble with history’s lessons. We cannot remember without experience, but we can learn, clumsily.

The Kingdom (2008) by Damien Hirst bares its teeth behind smiling Emily Carr, with Woo, her monkey. Inspired by Hirst’s Spot painting, Willey dots the background of a juxtaposed BC bicycle rickshaw, touring, spotting the sights? In the pale distance, a tall sail is in harbour, reminding us of the passage of time and analogous intention for expedition. Hirst is an interpretation of the monetary credence a prominent sale (Saatchi, for Hirst) can affect the life of an artist, and reminds of Carr’s poverty. Both creatures are out of their habitat, as well. Wooing us with the unfamiliar, challenging our comfort zone poses risk to insular lives. According to Willey’s pictorial interpretation, this financial transaction brings artist and their work from provincial to international status in the public’s perspective. Utilizing Hirst, Willey distinguishes provincial providence with the strength of Hirst reputation, which is communicable.

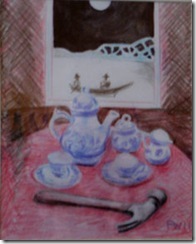

Willey reveals reflexive aggression with a hammer placed near very delicate teacups, symbolizing a past still present (Tea with Julian). Julian Schnabel smashed his crockery. Willey shatters with associated imagery, demonstrating the calculating transgression of colonialism and pejorative provincialism. By painting aboriginal boaters riding on a moonlit waterway in the tearoom window, Willey reiterates the impact of inaction.

Woman on a Bike (after De Kooning) brings restlessness to Willey’s show. Uneasy, yet breaking out of his placid cerebral visual vocabulary, Willey embraces past influences, allowing his restraint to burst out with arrestingly substantial, attacking strokes and tight composition. De Kooning, along with other European expats were once “provincial artists in a provincial capital, living in the shadow of Europe, who woke up one day in the 1950s to discover that New York was the metropolis of art and they were the unlikely, paint-splattered princes of the city.” Aside from the fame and fortune, De Kooning found this change oppressive. [2] Willey includes the bicycle we found Hannah Maynard riding in several other works to assure continuity, to corroborate that there is consequence to non-provincialism status causing interference to an artist’s journey.

The largest work (Carthage) refers to the North African city founded in Virgil’s Aeneid. Willey exudes a salient, crepuscule timbre that launches a reverie, noting civic improvements that marginalize people, relegating them to boarders of a watery divide. The work is a tribute to Turner who emulated Claude Lorrain. Where in the Lorrain and Turner works there is a tenebrous luminosity, in Willey’s painting, with Willey’s deeply amiable colours shows us his optimism and we anticipate favorable outcome to environmental alteration, in spite of provincial circumspection.

Vanishing Point borrows a De Chirico streetscape where surrounded by a diffused orangey glow, Willey shows examples of historical buildings in isolation and between, segregating past and present, distant trestles creating a provincial surrealism segregating memory, present constructs and future possibility. Willey demonstrates the affect of isolation. The past and present edifices are inaccessible, and we connect with the girl with a hoop, endowing playful abandon necessary for creation. Maybe it’s from Hannah’s bicycle.

Philip Willey found himself in Victoria BC around 40 years ago. “Victoria has been good to me”, he says. Speaking with him, he is ready with a tapestry of stories. One of those world travelers that hobnobbed with soon to be famous artists along the way, Willey has engaged with a veritable whose-who of art icons. A former board member of Open Space Gallery and writer for numerous art magazines while sustaining his art practice, Willey has been, both abroad and here in Victoria in the welcome sphere of provincial life.

Provincial Life

New Paintings by

Philip Willey

Spiral Café

418 Craigflower Ave

Victoria West

6 September – 3 October 2011

Watch video

[1] Halbwachs, Maurice. 1992. On Collective Memory. Trans. And ed. Lewis A. Coser. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[2] http://www.robertfulford.com/Dekoonin.html

“ A Myriad of Truths “

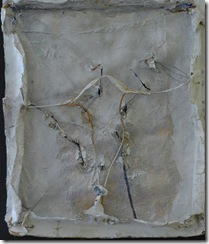

Myriad of Truths is a passionate undertaking where synchronistic plots appear in painting and sculpture, divulging illusory stories. Mythos strives to disclose visual legends she senses. Working with mystical knowledge from many cultural inspirations, there are literal and ephemeral references to allusive mystic energies. Bone and feather brings the essence of creation and nature into play, allowing the subjective choices to supersede objectivity with a skill and adoration for how the materials originate. (Tunnel of Eternal Return) Bringing images together with found objects, Mythos layers and develops her personal archetypal narratives. She demonstrates the truth as she experiences it, truth that has a universal realism although the work can be mistaken for cultural appropriation.

In his review (1)of Cultural Appropriation and the Arts by James O. Young (Blackwell Publishing, 2008) John Rapko points out that “cultural appropriation dissolves under scrutiny.” “There is little left for the philosopher to say other than to urge, with Picasso, artists to steal.” A warning about objects or content use by an ‘outsider’ may decrease the “richness, an idea, a style, or a motif; and of a subject or 'voice'” is immaterial in this work because Mythos heightens the viewer’s awareness of primordial forces that dominate a variety of aboriginal cultural arts, allowing her own voice to manifest in authentic intermingling imagery.

An autodidactic artist, Mythos’ production is vigorous and dedicated, although itinerant with each thought process she engages in. However, she adheres to the veracity of the moment, producing ardently with a mostly muted monochromatic palate that writhes with dream-like visions, sharing her consideration and veneration of ancient enquiry processes. A Jack Shadbolt introspection can be seen, yet Mythos’ probing is more eager, an internal investigation that utilizes beings challenging surfaces with combating strokes. Pairing collage sculptural elements with painted surfaces, Mythos assembles her strength’s conviction.

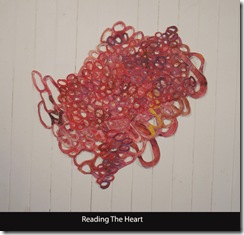

Mythos’ latest work (Rebirth Canal and Ribbed Tunnel of Eternal Return) begins a new exploration with intensely warm colour and unfalteringly feminine shapes. This work projects kindliness with intense assurance, confronting the value of integrity. What will Mythos mythologize next? She has begun to unravel a myriad of truths.

A Myriad of Truths

Artist: ‘Mythos’ aka Tessa Fenger

Olio Gallery

5 – 20 August 2011

614 ½ Fisgard St

Victoria BC

By Debora Alanna

Watch Video

[1] http://ndpr.nd.edu/news/23644-cultural-appropriation-and-the-arts/

In his review (1)of Cultural Appropriation and the Arts by James O. Young (Blackwell Publishing, 2008) John Rapko points out that “cultural appropriation dissolves under scrutiny.” “There is little left for the philosopher to say other than to urge, with Picasso, artists to steal.” A warning about objects or content use by an ‘outsider’ may decrease the “richness, an idea, a style, or a motif; and of a subject or 'voice'” is immaterial in this work because Mythos heightens the viewer’s awareness of primordial forces that dominate a variety of aboriginal cultural arts, allowing her own voice to manifest in authentic intermingling imagery.

An autodidactic artist, Mythos’ production is vigorous and dedicated, although itinerant with each thought process she engages in. However, she adheres to the veracity of the moment, producing ardently with a mostly muted monochromatic palate that writhes with dream-like visions, sharing her consideration and veneration of ancient enquiry processes. A Jack Shadbolt introspection can be seen, yet Mythos’ probing is more eager, an internal investigation that utilizes beings challenging surfaces with combating strokes. Pairing collage sculptural elements with painted surfaces, Mythos assembles her strength’s conviction.

Mythos’ latest work (Rebirth Canal and Ribbed Tunnel of Eternal Return) begins a new exploration with intensely warm colour and unfalteringly feminine shapes. This work projects kindliness with intense assurance, confronting the value of integrity. What will Mythos mythologize next? She has begun to unravel a myriad of truths.

A Myriad of Truths

Artist: ‘Mythos’ aka Tessa Fenger

Olio Gallery

5 – 20 August 2011

614 ½ Fisgard St

Victoria BC

By Debora Alanna

Watch Video

[1] http://ndpr.nd.edu/news/23644-cultural-appropriation-and-the-arts/

Monday, July 18, 2011

John Luna’s Home Show and sale by Debora Alanna

PART 1

Eyes born of night

are not eyes that see:

they are eyes that invent

what we see.

From: The Constellation of the Body

by Octavio Paz. Figures & Figurations (2008)

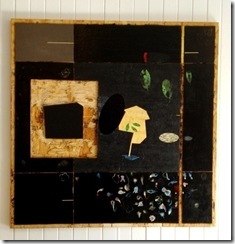

Permitting an elucidating intimation of intimacy born of layers of meaning, a sampling of John Luna’s previously exhibited painting over the last decade graced the walls of his home for a two-day glimpse this past June. Luna’s pellucid offering was too briefly presented. The time allotted too fleeting. Like a novel that engages you within the first sentence and you must return to at the earliest opportunity, Luna’s work demands further attention. Luna’s art takes time to breathe in - each breath imbibing a persuasive aroma of an intricate, sensuous mystery. Windows of confident tenderness and convincing ache, where indulgence of beauty’s excruciating disposition appears entail more than a peek.

Untitled (Delft Shepherd to Ghost) from Untitled Suite (#5/8) (2000) might be titled to refer to a period of Delft blue faience where glazed earthenware decorated with opaque colors may implicitly direct us to that historical time and place, to a shepherd on a plate in the 1600s, a nostalgic pastoral simplicity, to survival’s necessity. The wagging ghostly finger could be the subtext to shepherding of relationships, or a reference to the movie, “The Good Shepherd” based on Norman Mailer’s book, Harlot’s Ghost. The allusions are all conjecture. We cannot know without asking. The naming of this work suggests how the viewer may enter into thinking about the work. In her essay, “The Critic as Cosmopolite: Baudelaire’s International Sensibility and the Transformation of Viewer Subjectivity”[1], Margueritte Murphy cites Charles Baudelaire’s inquiry into understanding Chinese ceramics:

What would he say, if faced with a product of China—something weird, strange, distorted in form, intense in color and sometimes delicate to the point of evanescence? (…)—it is necessary for him, by means of a phenomenon of the will acting upon the imagination, to learn of himself to participate in the surroundings which have given birth to this singular flowering.

What is important is the ability of the viewer to intervene, to wander in the bucolic. Scouring the surface, unlike Jasper John’s search in Good Time Charley (1961), Luna’s encircling is caring while circumventing exactitude. Perhaps learning its definition, he traverses liberty as he circumscribes Eros, a paling, subtle space. Bulging, blistering blue with familiarity and hope, what is most striking is the luminosity that sings of haunting memories, which cannot be titled.

Buttress (2001) portrays an encumbered, covetous and madly reinforced vigor. Using fierce Franz Kline black, charged ominous rivers streaked with vivid blue vitality washed with pale yellow thrusts between arches of intractable fleshy tenderness. The intermediate is decisive, intervening with separating dominance. Leaning, favouring the brighter, widened curve on the left a spilling of watery xanthous bleeds and diverges to the other marred, withdrawing sphere that seeps out transitory yearning, wistfully.

Drawn in the peripatetic spirit of Dali’s “Catastrophic Writing”, Quatrefoil (2001) is an ominous disclosure where adversity is intertwined within the strengthening structure of the four delineated familial foils, interlocking power. Luna’s roughly stretched thick, palpable fawn painted burlap calls attention to the coarse fabric bite and endurance of the wood support, which holds the uneasy shield. A confused, stained interior of rough, circuitously drawn outlines with meandering marks, awkwardly. Oozing of cobalt infiltrates, articulating the ideal arising from absence:

For his art did expresse

A quintessence even from nothingnesse,

From dull privations, and leane emptiness:

He ruin’d mee, and I am re-begot

Of absence, darkness, death; things which are not.

From: A Nocturnal upon St. Lucie's Day by John Donne

Luna’s East Estuary (2002-2003) is where billowing courses of preoccupied energy meet pressing tides of change. The heat, smarting red infiltrates. Rabbit skin glue pigments under white peeled paper, channeling the widening horizontal waves ripped by underlying crimson, his colour is grounded and mortal. Impasto and tear texture the breakers. Clyfford Still: "I never wanted color to be color. I never wanted texture to be texture, or images to become shapes. I wanted them all to fuse together into a living spirit."

[2]

Luna fuses an emergent surge.

Luna paints silence, a quieted whiteland, where the void is incised by elliptical apertures, sacred Yoni, opening into deified space. Data, Davadhvam, Damyata (2002) cleaves like an avatar, illustrating the personification of virtues described in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishads. In his poem, The Wasteland, T.S. Elliot adopts characters’ qualities from the second Brahmana passage of “The Three Cardinal Virtues”, [3] datta (charity), dayadhvam (compassion) and damyata (restraint). [4] Launching this precept, a path of moral excellence emerges. But Luna includes 4 ellipses [5] in this work. Cut carefully, vertical vacancies in the painted surface readdress the virtuous course, acknowledging human inadequacy. The lowest and nearly determined opening has the remnants of the elliptical cutout hanging. Discerped from virtuous ideals, and dangling, mortality demands a connection between a suspended vision. Needing to know the process is a means to realize what is wanting.

Winter Composition (2003-2004) is a flourishing use of material to build up a stormy palette, inundated with chilly thrashing. Seemingly blithe strokes of sky meander above restlessly smeared, sandy earth. The watery discharge below jumps, cuts and smears into the middle ground from somber suffusion. Amee F. Carmines wrote that Paul Celan explores the ‘frozen rubble of language and humanity, salvaging a warm pulse, even though the carrier of that warmth is banished and burned. He seeks something that can only be found on the edge of silence” [6] I’m wintering over to you. ~ Paul Celan (Snow Part) [7] Luna’s winter swells and thrashes with contrapuntal intensity of harmonious discord. Influencing turquoise is tortuous and pulsating, pervading the central hush – Luna’s brumal season.

Canyon [front] & [verso] has a similar dual existence as Window (2003-2008), Sign (2008-2009) and Messenger (2008 -2009), reviewed on the Exhibit-v blog . [8] Canyon [front] is a chasm where erotic contemplation hovers and becomes a melancholic memory held tight and succinct. Canyon [verso] ties memory, reticulating reason into a grey twist, an entwined prickly tract.

It takes time to absorb John Luna’s paintings. Because he gives you plenty of surface loci to focus and ponder, suggestive materiality to feel, poetic maturity to allow thought divergence, expand insight. And profound scholarly knowledge references to discover, if willing, which will ultimately stimulate further awakening. The looking cannot be rushed. He dissuades cunctation, as his work identifies urgent, purposeful questions that demand concentration, now. Precipitance will prohibit knowing, or what can be known or felt. Feeling is germane. Surfaces are rough, scarred, besieged with colour and incised with distress. The works caress space and we recognize the longing for delicacy of soul’s refinement. Luna’s paintings are strength weighing, stretching fear’s wrapping to breakage, the point of positioned views where past presents and future is possibility.

PART 2

Over a diminutive tajine of salt, bread and Moroccan soup, John Luna spoke about his inspiration, motivation, and art practice. Tumbling ideas, interweaving angulated poetics with quotes, I tried to assimilate each explanation in hyperspeed tangents of thought and I wandered from his original remarks, over and over. Looking at my notebook afterwards, I realized I had only snippets of the conversation written in a scrawl I would barely decipher, having to write at least as fast as John Luna spoke, which was not possible. Using a recording device might have been useful, but would have detrimentally coloured the conversation, I thought. So, I will relay a collage, morsels of Luna’s acumen in no particular order that I managed to learn. His ideas are all with variably specific contexts, and are recorded as faithfully as possible, however, are not transcribed entirely verbatim.

John Luna likes to be at home (big thing), home being where there is an adequate language of relationship, being somewhere and not be there, maybe no where in particular. He refers to Paul Celan’s The Straightening: “no body asks after you”. He says these lines are poetic directions, and “in part, risk language”.

The topic of Jasper Johns’ ruler paintings demonstrate Luna’s attention to use of tools, where he observed an absence and inertia. Inertia resulting when wants, fault, problem, over shooting, and bearing exist. Abandon is a kind of absence, proof you were there, being led array, “an alleviation of burden”.

Luna imparted that your (your – collectively, he uses the collective ‘you’, as opposed to ‘I’ because ‘I’ is a distraction, “pain of ass”. He is uncomfortable with personal, indirectness) dreams are microbes, little lights that expiate burden. Slow insufficiency pours. Homonymy is how dreams work.

He talked about the serious repetitions of gesture. “Being in slipstream feeling.” He relayed the “way of relating to equatorial fatalism” - self secrecy. And mentioned an “anxious, just in case (feeling) vs. compulsion”. He spoke about fear as a transaction. And ethics, which are “hard to make clear”. He speaks about Beuys as a resistant character, and impurity, as the action of Darwin.

Paraphrasing Cezanne: ~ “I will always be the primitive of the path I discover.” ~ Luna explained that in his work, Eros is “a state of tension, all at once available”. Although a distraction, as in Rauschenberg (Luna says). The act of irritating a surface becomes fatigue, tension. Tension is valued. Having a job, task, a reusable one that evolves ~ the temporary doing and undoing of knots. Landscape relocates the crisis/problem history with structure. And can be “danger swapping”.

He refers to 'Bataille' and 'Formless' (referring to Formless: A User's Guide by Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind E Krauss), an invaluable book for him. He is now reading Krauss, The Optical Unconscious, which he also thinks is great.

He talked about character development, about being an artist/teacher, the stability required to make art with art school as an outlet, providing freedom. And trust. Creating an imaginary social life, as expression - this becomes an “expanding conceit”. Luna relays how relationships shift and how the blurring autonomy of work impacts the domestic setting.

Auspicious and humbling, Luna wants to be “just domestic” make work about the lyric domestic space, disappear into the domestic landscape, and be with the work. Endeavoring to pass into anecdote, he creates persona, and resists insecurity. John Luna is treasure.

PART 3

Giacometti approached, nuzzled by a dark silky guardian. The dog bade him welcome. “John Luna has been waiting for you.” the dog communicated. The tall, walking man’s suspicious eyes approaching the doorway asked, “Why?” Giacometti’s look returned, “Because.”

With a mouthful of home-made steamed baguette dripping with melted butter, Dante appeared in the doorway, beckoning and spoke excitedly from the porch. “In this house dwells a divine comedy. St. Lucy’s eyes are everywhere. Courtly love challenges intimacy lyric.” Upon entering, a quatrefoil was secreted, visible through a glass door, mirroring.

Inside the salon, they faced newly painted grey walls gathering abstracted thought. Straightening the aged estuary canvas, “(It) shows me up better.” Luna grinned. “It peels away memories,” Jasper Johns added, having just coming into the room to join the others.

Having come into the house silently, the others saw him beyond a cut-out aperture to the fore room. Paul Celan spoke, sharing his usual complexities as he turns over one of Luna’s reversible paintings. “Glad to see I can see both side of the questions you pose.”

Smelling of ages, Cezanne floated in, stealthily hovering behind Luna, whispering, “I swear I have seen you somewhere, some winter on the Riviera, perhaps?”

Poking his finger rhythmically through some ellipses, T. S. Elliot shouted to the others from an adjacent canvas, “Dot, dot, dot and into infinity…” (No one could remember exactly when he arrived.)

Baudelaire wandered up the stairs and joined, “There is a shining girl hanging from a tree!” “Let’s drink some of your redolence over coffee and talk.”

Absence is present.

25 & 26 June 2011

Victoria BC

[1] http://www.palgrave.com/PDFs/0230551165.Pdf

[2] Clyfford Still, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 1976, p.123

[3] http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Troy/4081/WasteLand.html#431

[4] http://www.archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/east-meets-west.html

[5] “[Greek, ellipsis, a want, defect, ellipsis < to fall short, leave undone > en-, in + leipein, to leave].” Webster’s New World Dictionary. World Publishing Company. 3rd ed. 1958. Print.]

[6] www.unca.edu/postscript/postscript5/ps5.5.pdf

[7] Schneepart (Snow Part), translated by Ian Fairley (2007)

[8] http://exhibit-v.blogspot.com/2010/08/john-luna-tyler-hodgins-storage-room.html

0 comments:

Post a Comment

Thursday, July 7, 2011

Blair Taylor “ You Blew It “ by Debora Alanna

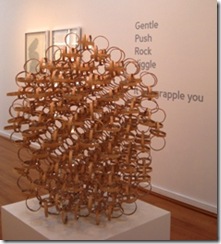

Blair Taylor dreams white dreams of bare efficiency colouring consciousness. Little rises of figures in arrested action impale and huddle, reflect and evince sensation. He delineates and miniaturizes his dreams into equal portions, creating language components, meronymy where isolated parts of dreams relate to his entire dream lexicon. The dreamscapes colligate with size and form. Unnervingly smooth with anonymity, Taylor’s ambiguous figures interplay amongst diverse variations of open architectural configurations. The figures, still as statues from the Abu Temple in Tell Asmar composedly contest. Taylor produces drama within dreamy smooth spaces.

Voyeurs into his dreamworld, we peer into lulling whiteness. Taylor sets his dreams on stark plinths in ordered rows. Taylor’s sculptures can be paralleled to Sandro Bernardi’s assertion about film: 'Il cinema come insiemi infiniti' (infinite sets)[1]. Or scenes like comic book captures that draw tidy, simplified significance with one important dreamed moment, and then another and another. The exhibition space ticks like a silent clock.

Fine, sinister silhouettes summon mysteries’ shadows, contrasting the blanched incidents. Oneiric definition and separation haunts stealthily. Whitened meandering cords suspend white-painted oval speakers narrating. Taylor whispers his dreams into our ears in two locations on the side and end of the exhibition space. Unlike George Segal’s white peopled vignettes, influenced by John Cage to “connect art with tangible reality”, [2] sitting down between Taylor’s undertones, the captivation translates the dreamscapes’ without associating to any particular delineation of his sculpted dreams or our awake world. The auditory sublimates visual wanderings, disengages us from private associations visually presented, developing the pictorial dreams as movie sounds will brings fresh scope to the pictures on screen.

Taylor works small, keeping involvement disconnected in spite of pragmatic building. The events depicted are affectedly dramatic. In her 1999 feature article in Kinema, Oneiric Metaphor in Film Theory, film theorist, Laura Rascaroli writes:

For Jung, dreams develop according to an authentic dramatic structure, formed by a phase of exposition, in which setting and characters are presented; by a development of the plot; by a culmination or peripeteia, containing the decisive event; and by a lysis or solution. [3]

Each of Taylor’s works punctuate with some decisive moment, point of intensity. We are obliged to imagine a resolution. Clarity through simplicity details austere incidents and decorum presupposes we accept that drama will result in a resolve. Preoccupied figures situated in architectural isolation are analogous to painter Paul Delvaux’s Dawn over the City (1940). Unconscious solutions wake a dreamer. Like a Surrealist perplexity, Taylor’s sculptures are subterfuge. [4]

Thinking about Taylor’s numerous stair configurations, there is a structural interrelation to Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s stage design that transformed Die Tragödie des Teufels (The Tragedy of the Devil) [5] at the Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich in 2010. This opera transported the “Hungarian Faust”, Imre Madách’s The Tragedy of Man into an architectural environment dominated by a prominent luminous white staircase. The stairs conceptualized can signify ascension or descending, a substantial symbol illustrating the timeless struggle to forestall tragedy. “Mankind, it seems, is beset with plenty of inherent evil and requires no outside agency to foment more.” [6] Taylor’s work encourages a devilish bias as many of his sculptures are skewered with quiet violence.

From: There are Crimes and Crimes. (Act 1 Scene 2) by August Strindberg (1899)

MAURICE. Well, if we had to answer for our thoughts, who could

then clear himself?

HENRIETTE. Do you also have evil thoughts?

MAURICE. Certainly; just as I commit the worst kind of cruelties in my dreams. [7]

Through Taylor’s work we collectively experience different versions of unconscious darkness or “Shadow”, an archetypal representation of what disturbs us, about what we do not want known, what we are pained to know and need to know. His use of white distils, counters malevolence. “When it [shadow] appears as an archetype…it is quite within the possibility for a man to recognize the relative evil of his nature…” [8] Utilizing objects (spears, swords and flying projections) for which eroticism is symbolically characteristic, [9] Taylor’s sculpted consciousness is as evocative as Uccello St George impaling his Dragon (1456), a 15th century symbolic through and through of male eroticism, killing ‘sin’, personifying ruin. Taylor stills, piercing ruin’s intensity with an arresting perseverance to remember.

Blair Taylor

" You Blew It"

Art Gallery of Greater Victoria - LAB

22 April - 3 July 2011[1] Sandro Bernardi, 'Il cinema come insiemi infiniti', Filmcritica, 332 (1982), pp. 98-105.

[2] http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/guggenheim/education/05.html

[3] Serge Lebovici, 'Psychanalyse et cinéma', Revue Internationale de Filmologie, 281 (1948), p. 53

[4] http://www.yuricareport.com/Art%20Essays/SurrealismAndTheUnconscious.html

[5] http://www.ilya-emilia-kabakov.com/index.php/installations/die-tragoedie-des-teufels/description

[6] http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/03/arts/03iht-Loomis3.html

[7] http://www.gutenberg.org/files/14347/14347-8.txt

[8] C. G. Jung, Aion in The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, ed. William McGuire et al., trans. R. F. C. Hull, Bollingen Series XX (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1954-79) Vol. 9/2, p. 10.

[9] http://www2.arnes.si/~uljfdv15/library/art06.html

Tuesday, June 7, 2011

The Rosen Women, exhibit reviewed by Debora Alanna

Hinda Avery’s billboard sized paintings proclaim a resistance to war, to the Jewish persecution and decimation in the Holocaust or “The Shoah” ([1]), confronting the repercussions of another and very different time and place than we in British Columbia presently experience. With a series of photographically documented wartime events that are reclaimed and reconsidered through buoyant optimism, Avery advances the approach of and need for collective female resistance to the protracted outcome from the Holocaust calamity. The work exhibits actions that combat the oppression of morale, showing how to withstand and counteract the long-term effects of the tyranny and murder of about 7.3 million European Jews at the hands of the Nazis ([2]) and help generations’ consideration to follow. Avery’s work counters the enduring harmful influence of this World War ll slaughter and residual heed to Nazis’ measures by painting the largess of campaigning women that are colourfully strong and infectiously cheerful - familiar and familial.

The Rosen Women upholds and fosters decisive denotations of female resistance fighters. Utilizing photographic portraits, Avery reconstructs the document images onto her canvases. She substitutes her female family’s faces on these painted compositions, keeping the original stance of people experiencing the processing prior to the genocide and on soldiers preparing for war. Additionally, Avery accentuates the women’s features with enlivening smiles.

Avery begins each work with pencil drawings that she leaves visible, while colouring in various details. We witness the piecing together of partial memories. Some more vivid than others. Some just outlines, some vaguely textured with hints of specificity. The bare architectural perspective rendering is unpainted in many places, showing structural layering. Layers build understanding. Avery shows how history’s narratives begin with the simplicity of a thought, a mark.

Avery discharges healing ammunition through the fiery force of expressive opposition to typically haunting war images. Injecting beaming countenances onto the scenes of Nazi invasion, parading explosive happiness in fitness exercise preparation (The Rosen Women working out, just before their advancement on the Nazis), and wielding weaponry to attack oppressors (The Rosen Women – Resistance 1) Avery displaces impassivity with proud determination, asserting joy in passionate resistance. Painting female heads on male physiques of an exercising assembly, Avery asserts an integration of the perceived physical strength of masculinity with female intelligence.

Leafy textures, shadowy garden-like patches that camouflage,

embeding the rifles of the resistance fighter busts (The Rosen

Women in their camouflage) seems to ask questions Blake posed

in his 1793 poem, Visions of the Daughters of Albion:

Tell me what is a thought? & of what substance is it made?

Tell me what is a joy? & in what gardens do joys grow?

And in what rivers swim the sorrows? and upon what mountains

Wave shadows of discontent?

Avery’s camouflaged gardens defend against the rivers of sorrow because her mountainous formations protrude gunning female power.

In War and Popular Culture: Resistance in Modern China, 1937–1945, the author Chang-tai Hung speaks about challenging society to personalize the death and destruction of war by considering the power of female symbology in street theatre. “If the patriotic resistance struggle could somehow be reduced to human terms, if it could be individualized as a person —a flesh-and-blood human being endowed with authentic feelings and experiences—then powerful nationalistic reactions among the people might be evoked… Their ability to understand and identify with the female symbols presented to them, to feel that "she is one of us," was therefore crucial to the success of the play and to the creation of a sense of common heritage and purpose.” ([3]) Avery’s heroines become characters portrayed by her immediate female family members symbolizing moral responsiveness (The Rosen Women – Resistance 2) and (The Rosen Women – Resistance 3). She includes her own portrait amongst these characterizations. Her paintings cultivate the spirit of solidarity with women we can relate to, creating the bridge between subject and viewer. Avery’s work identifies a connection that enables the viewer to aspire to countering oppression, utilizing the painted subject’s comic pathos. We can confront the horror because of Avery paints theatrical cheerfulness.

From the Harold Bloom collection, Literature in the Holocaust, Mark Cory’s essay, Comic Distance in Holocaust Literature (204): “Beyond marking moral boundaries and establishing nuances of credibility in incredible circumstances, the comic in Holocaust literature also functions as resistance, as protest.” ([4]) Establishing authenticity with the composition’s photographic documentation Avery’s comically happy resistance fighters become protestors. Her risible interpretation launches The Rosen Women with resonant integrity, producing an ethically comedic response to the staggering decimation the Holocaust created.

Avery’s subjects release intense curative powers, heightening the complicated and difficult memory of the slain and afflicted. We are shown an accessible way to think of the carnage. Avery challenges us with effusive enthusiasm, painting a vigorous force.

The Rosen Women by Hinda Avery

Martin Batchelor Gallery

712 Cormorant St

Victoria BC

May 28 - 23 June 2011

[1] http://frank.mtsu.edu/~baustin/holo.html

[2] Gilbert, Martin. Atlas of the Holocaust 1988, pp. 242–244).

[3] Hung, Chang-tai. War and Popular Culture: Resistance in Modern China, 1937-1945. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1994 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft829008m5/

[4] http://www.scribd.com/doc/40067590/10/Comedic-Distance-in-Holocaust-Literature

Friday, December 3, 2010

Shannon Scanlan’s The Blue Room by Debora Alanna

Shannon Scanlan’s The Blue Room, a sculptural installation at the 50/50 arts collective is not only about the implications of the colour blue. Nor is it only a vacancy, a basic dullish cerulean blue room that we enter. The gallery anteroom or main space becomes the preface to a story, until we chose to cross to the other side. Because Shannon challenges us, creates a narrative with a path to follow, a journey to undertake, a discovery to make.

We need to transverse and duck string strung across the width of the gallery, to follow the prescribed footpath she has demarked. Be in danger of distraction by blatant signage, an Albers-like 2-tone squared centre that encompasses an entire South wall, forcing our diversion from the final destination. If willing, we need to find a channel within the strung string, sectioned for relief or temporary repose. Become frustrated and free when we cross a river of string hung too low for consenting adults to cross without circumventing by stooping, lowering ourselves.

If you remember Antoin Pesvner and those mathematical cohorts of his, we can think of this pink string (pink for contrast in a blue room, the artist says) as a measurement of sorts. Pink is more than a contrast, however. The colour alludes to the pink Pop to come, measuring our tenacity and belief in our (Scanlan’s) narrative. Measuring our willingness to get to the other side. Measuring our compliance to follow a path or forge our own, without breaking the string barrier. Avoiding the trap of staying in the middle reprieve of a wider space between string strung and retreating.

So where are we after our odyssey? Stockholder curtaining brings us into an alcove. Bright with pink lighting and reflective paper cut into rectangular strips splash hot colour and contrast, We are brought to where there is a revelation, a self-discovery of a set of beliefs not quite formed, but felt, a threshold.

Our trek is not quite over. We need to navigate back (yes we must). No longer experiencing an arduous peregrination because we know where we have been, have accomplished tasks to arrive at the consequence of the yarn, we need to leave and reflect on the reflective. Shrewd, The Blue Room is a metaphor for lowered states that will adjunct to another, happier place, with persistence to reroute, even digress. You can see the happy place, but you cannot reach it without belief in your story.

Review by Debora Alanna - Photos by Rory Lambert

THE BLUE ROOM

50/50 Art Collective

2516 Douglas St

Victoria BC

19 November – 8 December 2010

We need to transverse and duck string strung across the width of the gallery, to follow the prescribed footpath she has demarked. Be in danger of distraction by blatant signage, an Albers-like 2-tone squared centre that encompasses an entire South wall, forcing our diversion from the final destination. If willing, we need to find a channel within the strung string, sectioned for relief or temporary repose. Become frustrated and free when we cross a river of string hung too low for consenting adults to cross without circumventing by stooping, lowering ourselves.

If you remember Antoin Pesvner and those mathematical cohorts of his, we can think of this pink string (pink for contrast in a blue room, the artist says) as a measurement of sorts. Pink is more than a contrast, however. The colour alludes to the pink Pop to come, measuring our tenacity and belief in our (Scanlan’s) narrative. Measuring our willingness to get to the other side. Measuring our compliance to follow a path or forge our own, without breaking the string barrier. Avoiding the trap of staying in the middle reprieve of a wider space between string strung and retreating.

So where are we after our odyssey? Stockholder curtaining brings us into an alcove. Bright with pink lighting and reflective paper cut into rectangular strips splash hot colour and contrast, We are brought to where there is a revelation, a self-discovery of a set of beliefs not quite formed, but felt, a threshold.

Our trek is not quite over. We need to navigate back (yes we must). No longer experiencing an arduous peregrination because we know where we have been, have accomplished tasks to arrive at the consequence of the yarn, we need to leave and reflect on the reflective. Shrewd, The Blue Room is a metaphor for lowered states that will adjunct to another, happier place, with persistence to reroute, even digress. You can see the happy place, but you cannot reach it without belief in your story.

Review by Debora Alanna - Photos by Rory Lambert

THE BLUE ROOM

50/50 Art Collective

2516 Douglas St

Victoria BC

19 November – 8 December 2010

No comments:

Post a Comment