Sunday, February 1, 2015

“Oscillatio” exhibit by Sarah Cowan and Connie Michele Morey reviewed by Debora Alanna

‘Oscillatio’

Sarah Cowan and Connie Michele Morey

xchanges gallery

2333 Government Street, Suite 6E

Victoria BC Canada V8T4P4

9 – 25 January 2015

Review by Debora Alanna

Exhibit-v video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ROHNz8pHLjc

‘Our thinking tends to circle around established conventions whose basis is forgotten or obscure. Nietzsche proposed that the attainment of knowledge requires a ‘solid, granite foundation of ignorance’ for its unfolding: ‘the will to knowledge on the foundation of a far more powerful will: the will to ignorance, to the uncertain, to the untrue! Not as its opposite, but – as its refinement!’’

~ 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl, Daniel Pinchbeck, 2006, Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, New York, pg. 3

Oscillatio is the xChanges exhibition of work by Sarah Cowan and Connie Michele Morey. Together and individually they deliberate and establish truths that exist through paradoxical and simultaneous ideas. Each utilizes the sensibility of commonplace materials inherent in crafting. By using humble, naive media, both artists establish and work from this foundation to promote unfolding ignorance (see Pinchbeck on Nietzsche, above) and refines the unknown, willing the minute of substantial truths to exhibit within Oscillatio. Both artists have deep and profound knowledge of the human condition, but are willing to exemplify the adage, the more you know the less you know, a philosophical discourse found in agnoiology, the study of culturally based ignorance or doubt. Allowing themselves to work with modest materials, they begin to counter certainty with the oscillating stance of the ignorant/informed shifting on the precipice of the unknown and known.

Their materials and use are laden with emotional contexts because of the original intent of the materials used as a means of caring more, better although with the utilitarian outcomes crafts are crafted for, made to withstand, bolster goodness in harsh and impersonal realities. Cowan and Morey’s practices address basic material use through subjugation and ingenuity.

Cowan liberates paper with expert mastery, establishing a physical connection to her medium. Then, from the original flat beginnings she adeptly expounds frisson, embodiment of intense shudders through her absorption and incisive perception. Her rigour and deference to the limitations of paper are countered by Cowan’s testing and taxing of herself. The memory of this arduous process seems to vibrate within the work and becomes a channel for exuberance.

Morey challenges wool, fabric, notions, handmade toys and more from its original confines of homespun intent. Works nurture rifts unapologetically but offer accord at the same time. They coax nostalgia that triggers tension between approval and disapproval one might find in argumentative conflicts. She stretches the intent and physical limits of her media, her means to concurrently investigate universal discourse.

Their investigations are the veracity of thesis and antithesis, honouring differences and similarities, not with the objective of sanction or an opposing stance. Each artist allows their esteem for their fundamental, modest materials to be challenged and confirmed. A substantial range of exploration heightens the experience of coexisting works. Together they inform and enlighten the viewer about the wide spectrum of familiarity, ritual, play and work practices. Oscillatio is an interrogatory intervention where the oscillation process humans flout, breach, elicit and present are shared by being alive, given the credence of uncertainty.

Throughout Oscillatio, circles abound. Works engage, encircling the oscillating ideas that define existence. Groups of work define explicit processes that are sensed, felt, cannot be easily named. Spheres of influence, interest and personal though individual, parallel or contrary are persistent with shared domains that thrive in the honest pursuits of each artist. They reveal and disclose lives lived, the living being an encircling oscillation as a means to impart realms of exhilarating verve. Cowan and Morey allow an individualised introspective discourse and a unifying perspective on versions of the flux we sense, encounter, impart and epitomize throughout our lives.

‘In The Arcades Project, to cite is at once to explode and to salvage: to extract the historical object by blasting it from the reified, homogenous continuum of pragmatic historiography, and to call to life some part of what has been by integrating it into the newly established context of the collection, transfiguring and actualizing the object in the “force field” – the oscillating standstill (Stillstand) – of a dialectical image. The redemption of the past in constellation with the now, adumbrating in language a “nucleus of time lying hidden within the knower and the known alike” (The Arcades Project, N3,2), takes place in what Benjamin will call, in his 1929 essay “On the Image of Proust,” “intertwined time”. This is the temporality of montage.’

~ Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life, Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA., 2014, pg. 290-1

Cowan and Morey, each in their independent practice and through a year of collaborative thinking have produced work that ruptures the homogenous continuum of pragmatic research or practical consequences. Osscillato is a collective of ontological studies where the oscillating standstill of each work (see the Benjamin description above) involves a tension of conflicting ideas, taut opposition that focuses on the sustained relational commonality between the artists, what knits humanity over time and what can be discovered in Oscillatio’s tableaus.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Knowing’ / As logic weeps.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Knowing’ / As logic weeps - photo by Debora Alanna.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Knowing’ / As logic weeps ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

In the centre of the gallery, Morey has set a table with Paddleball / Bingo-Bango shaped distressed bats set in 2 arrays. Each paddle sports felted balls where rubber balls originate in the children’s apparatus’. Words of comfort are stitched with large patches, considerable sutures to the nebulous, misshapen wool orbs fixed with elasticised extensions to the paddles.

Attendees are encouraged to play, hit a woolly subject against a thinning pink, sand paper afflicted flat rounded blade. Paddling Morey’s paddleball is an unwieldy and rarely successful action because of the weight and ungainly shape of the grey woolly balls with added disproportion of thick patches and heavy stitches do not correspond well with the intended hitting surface. The entire exercise is wonky. And can be fun depending on why one engages in the challenge of this endeavour. Morey educates us through our play.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Knowing’ / As logic weeps. ~ photo by Amber MacGregor.

The balls become fuzzy, the elastics tangle. Oscillating movement of the boinging between woollen mass and stretchy flex in opposition to the propelling force of the player and the bat, a hostile though seemingly playful intent diminishes the idealised mean, the havens of existence named on the balls. The action targets the best destinations of refuge, wearing the spheres of sanctuary. Our ultimate needs become worn even with the best intentions and light-hearted engagement. Our logical selves suffer when we know what is between ourselves and others – the unexplainable outpouring of something, the bounce, the banter, the intertwining. When we know we have been the instrument of change, the knowing becomes the condition for our consternation and joy. Each elasticised bat conference is a reason for tears of laughter or lament, an emotional confusion. Leaving the game unattended without play, we learn nothing.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Knowing’ / As logic weeps. ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey

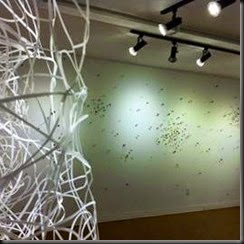

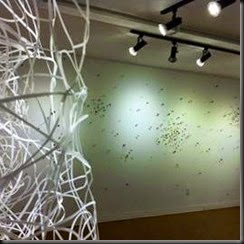

Connie Michele Morey - 'Oscillatio' installation of ‘On Knowing’ / As logic weeps(forground) & ‘Fingertip Cartographies’ /

As we name they planets, they dance (rear wall) ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey.

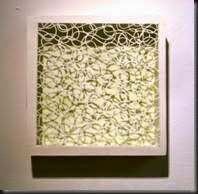

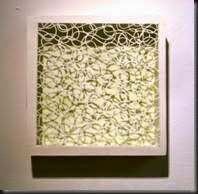

Sarah Cowan: ‘Untitled’ – installation.

Sarah Cowan: ‘Untitled’ - installation ~ photo by Sarah Cowan.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' - detail ~ photo by Sarah Cowan.

Cowan’s largest work is untitled but associated with Emily Dickinson’s second verse of the poem, ‘Of Being is a Bird’, with a slight change to the second last word – than instead ofthe:

It soars—and shifts—and whirls—

And measures with the Clouds

In easy—even—dazzling pace—

No different than Birds

Cowan’s work does soar, shift and whirl. Although she has with a measured, deliberate pace calculated the temper and extent of each segment of her four part work, she takes us aloft to realms of enigmatic mysteries clouded by our utilitarian lives. Through her inscrutable even pace, her serious fancy she has produced a spectacle dazzling in our presence, ferociously wild, intricate passages – no different than birds’ pace.

Sarah Cowan liberates large pristine sheets of white paper (3 x 8’ aprox.) from a static continuum. Beginning as a dance, a celebration of delight with spherical movements conjoined over the sheets, she widens her space, stretching her being to allow her pencil to clearly demarcate ubiquitous connectivity.

Sarah Cowan: ‘As I was making these, I kept thinking of myself as a young child. There were times in my life when I was absolutely exuberant, full of light, all bubbly (…) Maybe that is the child in me.”

She works with youthful certainty, allowing the definition of space to begin, extend from her dexterous manipulation of the flat plane through her sphere-shaped drawing. She defines circuitous living, lives lived intertwined, how they bond, how they curl and circle toward, away, together and apart. Cowan shows how life is a continuous dance, a comforting encircling togetherness yet with estrangement that is shown by each unique circling curve drawn. Cowan’s paper is embodied as clustered protuberances, interlaced auras evoking Cy Twombly’s scribbled knots but without his pathos. Cowan emanates airy elation bursting forth as a quatrain or quartet, four sustained intentions that ultimately work together as body language.

Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is…

~ from Four Quartets: Burnt Norton (1935) by T.S. Eliot.

Her circular advance and development is comprised of unique transfers of feelings, passages between changes and challenges to thought without verbal articulation of reflection. Lines became Cowan’s scheme to articulate power and strength, consternation and resolve through the adversity of the rhythm of stir to stop and start, breathing’s tautness and release all finding their integrity through her pulsating pencil. Lines show tenderness, vulnerability. Succession of round marks pursue cycles and transitions from one point to another, the lines between encounters, touch and retreat, endurance through the ache or niggle. Her fun in raising the drawing implement to the next point of ingress beginning anew, transformed her page with each line inscribed with roving intent.

Cowan’s work required immense stamina. Each work, its elements reiterate, amplify her ideas about the constituted fortitude in the oscillation experience. Cowan established how and what matters with her unremitting flow, fly over the page. She appointed marks, drew incisively, precision being the significant consequence of incessant, substantial strokes. Contours underscore urgency. Connectivity related the paths of bonds and networks, relational charges, the apprehension and relief of correlation. The unshakable flourish of Cowan’s pas seul, her intense circumnavigation of bubbling bursts, connecting corpuscles, cellular awakening throughout her boiling effervescent choreographed overlay becomes our focus that allowed the next stage of her work to find its own vigorous voice.

The next stage of Cowan’s intrigue began with an Exact-o knife cutting into the outpouring of marks. The outstretched paper rolled into a scroll of paper showed the current of lines of integrity, reliable shimmy and glissade, the stream of incised exactitude and meticulous austerity of movement. Removal of the centres of the curves left tantalizing, slender contours in the paper drape leading to her foursome of uninterrupted, protracted incantations. Cowan summoned the means to living with and without the breach of fissure and mend. She lures the timelessness of an ample and wondrous existence. Cowan worked through the trepidation entrenched in mistakes, utilizing the practical composure of belief in her oscillating configuration to attain the best one can be because of the conviction and engagement in a labour of love.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' – detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

Time, that oscillation between here and now, the instigation, activation – what was then and is future, the product and its consequence, the next step, the time between commencement and working within the core of the idea, its manifestation, its medium, the intermediary stages, the progression, the route, the handling and the manoeuvres through to the result – all these phases and junctures are inviolate, common to everyone as stages in living. Time demands and constraints are eloquently embodied in her work. Time management compels Cowan. Drawing her into a strict timeline with scrupulous care she translated this absorption as obdurate dedication. She shows us how to stay accommodating to the means of obtaining a meditative life while being intractable to our goals and especially, the outcome of perseverance through adversity. Cowan’s lessons are gleaned through her drawing practice, cutting dozens of paper circles from a sizable paper sheet. She transformed these humble acts into gossamer filament. Cowan’s sharp keen incisions becomes transcendent the way understanding lies beyond the scope of observation and insight. These works are independent of their materiality.

The final stage of her work required, expounds subtlety and diplomacy. To hang each work on the wall, adds sensitivity to the liveliness of the splendid, intrepidly cut sheets; she found the edge of the middle top point to acknowledge the splendour and modesty of its integrity. Her paper is animate. It glows and bustles. It breathes with every wisp of activity in the room. The four entities suspended, suspending abeyance, defer commotion and disbelief in the existence of animate spirit through her paper cut outs. The works hang upwards. This work holds and ensnares us simultaneously in awe and uneasiness at the interface.

Cowan encourages trust, conviction in possibility of the power of the unseen. Energising with their glow, these sustained tacit expansive notations became affable and congratulatory in their grouping. Perky, they oscillate between generous leeway of understated options and risk in confidence that might tear or be shorn by inadvertent contact that could defile the intact units. They generate concern about close contact, the way humans have anxiety about touch, not knowing, the uncertainty of limits, boundaries between people. The works show how we oscillate between perception and significant intention, meaning. These entities combine forces to assert the quietude explicit in regal stance.

The four cut-outs exemplify the invisible network of neurons and electric impulses that constitute our essence and emulate from our being with that unseen though omnipresent iridescence. Cowan reveals the foreboding we fear and love, the juxtaposition of the forbidden and divine within our natures. Her cut circles, all a-jumble when hung, retain their repeated movements, superimposing each other in an allied constituent of light and shadow. Converging and diverging colours of shadows and movement meet, touch, jostle and transition, lazing cloud-like formations modify with each flutter of a passing viewer, the gust from doors opening and shutting the way we quiver and flex as people pass us.

Sarah Cowan: ‘Untitled’ – detail. ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey.

She produces a liberation where circular drawings are scribed by a knife into thinnest lines holding each other together as an elusive unit. Cowan mediated the standard of intent. Her care, scrupulous scores devise an oscillating dance of shapes when the cut sheets are hung. Bodies of provocation vibrate and undulate as individual essences and as a collective association.

Cowan defines our characteristics in her suspended verses as the oscillating compunction of anticipation and expectation, willing to participate, waiting to be involved, needing interaction to be moved. She shows us to be individual. Each of her works are fundamentally unique in their execution, implementation and affect. Like humans as a group, they are the same make up, same arrangement and shuffle of nerves in circuits. Cowan’s sculpture bodies share their space and are fostered by their association to the others in their corps of lively dancers. She has cut through brisk vacillation and buoyant swing moves to advance a conglomerate of contour, an oscillating dance.

Sarah Cowan: ‘Untitled’ – detail. ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey.

Cowan’s oscillating forms are brilliant colour cacophony where no query is shadowy. She is specific about each line as interrogate of space, place and time, past and present in contrast and in unison. Shadows from these lines of enquiry become assurance, bolstering the challenges she poses of threadlike demarcation, sheer tenacity becoming the stringency of diaphanous light against blush and flush, shades of oscillation as intricate ripples, recurrence within absorbing circulatory machination.

‘In/Significance’

Hugo, tell me, dare I speak of love?

Connie Michele Morey: ‘In/Significance’ / Hugo, tell me, dare I speak of love? ~ photo by Debora Alanna

To the left of the corner, a little above eye level a woolly sheep’s backside is attached to the wall. To the right, a board spells ‘devour’ in the top half of the work. A black and white print of a nursery lamb image is collaged to a rectangular board rising slightly above the word’s picture plane. Small colourful felt balls punctuate the surface of the smaller board and seem to emit from, and/or be filling the mouth of the lamb, surround the lamb, floating about. The work is based on an encounter with a child that is known to the artist, their relationship through his growing maturity. Innocence devours, is allowed to assimilate, consume as much as they please of grace, gentle frequency and colourfast quality of love given. The giving needs to be as light as floating coloured particles, as diverse, as multifold. The giving of love and especially the telling must be a suspended act, or very particular, wily. Feeling without any imposed intention can be lightly, softly released. Otherwise, the lamb/ child could choke. Proclaiming or explaining the act of conferring love is suspect. Identify love, mention the giving? Ask if one may speak the depths souls seek? The answer is no because the lamb / child is an insubstantial cut out image as a result of that question, if posed. This question is for an idealised lambkin.

Morey shows the lamb as a black and white illustration in converse with the floating coloured balls because the idea of lamb/ child is not the child. The love/balls is/are tangible. The lamb in the picture cannot ‘speak’ for all the love surrounding it - being eaten by the lamb, devouring the lamb. The outcome of questioning if love can be spoken of is shown in the side sheep facing up, diminished, against the wall, sequestered. It is not in the main picture plane.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘In/Significance’ / Hugo, tell me, dare I speak of love? – Installation. ~ photo by Amber MacGregor

Questioning is significant and ‘In’ (conspicuous) because the sheep’s back is turned to the main, conscious of the ‘Significance’ of the naming - of the exchange, Morey makes a comical tantrum because naming, telling is desirable for the adult. The backward sheep, like adults, are aware that the amount of love given can be overpowering, becoming almost “sheepish” however much desired.

The mainstay portrait is disassociated with the cornered sheep, allowing the abundant love balls to drift, hover and soar because finally, the love giver knows better than to impede its love with prattle.

‘Cling taxon, Cling’ / A fixed point of view spins injustice. ~ Connie Michele Morey

Connie Michele Morey:‘Cling taxon, Cling’ / A fixed point of view spins injustice. ~ photo by Debora Alanna

Morey’s trio of wooden carts each set on its own cantilevering shelf filled with plastic balls, a coloured nipple atop each is accompanied by an invitation to ‘participate with the work’. It seems a nurturing requirement. The balls can be thought of as a collection of eyes, too, in wandering directions, none seeing the same direction or point of view. They can be the regulated opening for discharging, intake of thought, feelings, the nebs of the collected group of itinerant souls. They are the collective consciousness unconscious in their stand still.

Connie Michele Morey:‘Cling taxon, Cling’ / A fixed point of view spins injustice ~ detail. ~ photo by Debora Alanna

‘Taxon’ is an animal or plant group having natural relations. Compartmentalisation ruins what is worthy, cultivates immorality and implies injustice. Taxon is a natural grouping where changes occur to adapt and improve the longevity of the species. Taxons cling to their integrity. Morey encourages this hold that will prevent categorising; a violation of impartiality because bias is without integrity. Each taxon has veracity and evolves, too. Change can be upheaval for a species. This motion and stirring disorder is ongoing. Sometimes requiring an outward impetus to develop, the balls’ commotion seems at a standstill.

Connie Michele Morey:‘Cling taxon, Cling’ / A fixed point of view spins injustice. ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey.

The equal sized sameness of the balls are relations. The contents are relational, be it side by side, apart, together. The three four wheeled carts are a group, relational in their size, colour, material and accommodation. All carts have strings. All have balls as the end of their pull. One of the ball entities is waiting, in askance for the job of motivating, moving the cart, and it has no colour to define itself. The balls inside the draw correspond in their size, with coloured tips, although each of different colours all have the same dimension, substance, height. Each cart has a similar shelf but the shelves are in slightly different positions, varying access according to arm stretches available to reach. ‘Cling’, in Morey’s title consigns direction, as we must cling to the pull to move the cart, cling, as the shelf clings to the wall, cling as we might be happy the balls are contained and will not roll away when we pull the cart, clinging to their containment. Moving, the balls jostle against each other, rolling hither thither but do not cling except as an autonomous group of containment and, in that case, spin, may touch in the unison of transport. Unattended, without consequence they wait for interaction. Fixed views, although the interaction may change their view, intermingle to further alter views from the positions they held on the shelves. Retaining the same viewpoints would be very difficult because of the nature of their spherical bodies in motion and eventual rest, just so.

Justice necessitates a moral and political philosophy discussion. Morey offers a succinct triad of fixed viewpoints that translates the big subjects for us. We oscillate between justice and injustice because they are scary and difficult concepts. Often, we would in our daily rituals rather leave philosophy and politics for philosophers and the politicians. But we need to pull the cart by the balls, allow the balls of complacency to roll around to achieve discourse. Morey’s work entreats we craft our thoughts and actions to allow the roots of our thinking to be foundations for effective, just living. Not an easy plaything, justice.

The works on shelves are nearly the same unless the sculptures are contacted, played with allowing imaginative associations and a rapport to form, dialogue. Engaging with the carts allows meaningfulness to develop, memories to be made, nostalgia for the object in association with a pleasurable or frustrating or confusing or illuminating time spent with the plaything, carrier of eying balls detached from humanity’s taxon, Homo sapiens (Latin: wise man) - wise assessment and action is requisite to our grasp.

Morey’s work, her call for interaction can be understood as oscillating metaphors for the idée fixe and its horrifying outcome if we remain uninvolved. The sameness, the fixing of certainty without question, without doubt, without interplay is about the shelving of sincerity, the stagnation of perspectives. Passionate, unquestioned belief systems may result in amorality, vice or otherwise diminished character. Minimized individuality or individuals welcomed, groups clinging for any reason or emotional need or forming, reforming with the best intentions, including socio-economic groups will determine the flexibility or inflexibility of thought and deeds.

The quality of justice within society might become objectionable, detrimental to individuals, groups or the whole of humanity and may be defined by fixed viewpoints. Immovability will apply to the ethics of social decision-making, the doubtful categorising that people cling to in the absence of change or if no interaction occurs. Understanding is oppressed if viewpoints are shelved. Taking Morey’s carts out for a spin demonstrates the initiative required to take ideology off the shelf.

Sarah Cowan: ‘Untitled.’

flow

sway

wave

swing

sweep

ripple

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

Through 1967-1968, Richard Serra wrote a list of verbs ("Verb List" was published in 1972 in the book The New Avant-Garde: Issues for the Art of the Seventies) to act on, divulge and include his material process beginning with industrial stores in his studio. He devised the list to act on manufacturing materials considered non-traditional at that time. He wanted to experience the materials in unconventional ways. He wanted to counter Donald Judd’s ‘Specific Objects’, the consideration of sculpture as nouns and suppression of process. Verbs are words that show an action is happening, that a state of existence is taking place or condition, mode of being is occurring. The word is about the present, our acts, our status qualified.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

Cowan has named states, designations through verbs for us to think about in a framed wall mounted series. She listed verbs to associate with each of the 8 x 8” cradles painted various tints of light blue overlaid with one or two cut paper layers forming apertures, interfaces between her sensibilities and our experience of her work.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

These words read like a list of verbs from Serra’s list. Serra’s intent for each verb is implicit as she pairs the verbs with an infinitive ‘to’, which indicates the verb is independent in existence or function, having no overt subject. Cowan has omitted the infinitive because her words are more inclusive, allowing the work to describe meaning beyond the verb. Her verbs accentuate the work, give the viewer assurance, helping to fathom Cowan’s pieces. Like Serra’s use of verbs to act on the action – the focus is the action – Cowan’s verbs informed her work practice through evocation the verbs provided, although she is the subject, and we see her view of the world looking into the piece, or her viewpoint looking out, an oscillating perspective.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

Each work of this series has a sympathetic vibration, an oscillating resonance within and between each of the squares. The minute apertures are relatively small in comparison with the larger four works in the main gallery space. There is a personal space articulated within these works, an intimacy, a privileged discourse. The pulsating of the works seems more intense than the frequency of vibration of the larger works, a kind of incidence that reverberates although of her cut paper overlays on the diminutive views are slightly thicker with more substance. Each of these works has a friendliness, an alliance, one to the other and a depth of vision afforded by the coloured ground against the paper cutting. Perspectives of the imagery changes as viewers move across and back through the enclosed thresholds. The works offer a current of alternating, subsiding oscillation between fluctuations of attenuation and density. Light produces a scroll to read and get lost within the changing window view, affirming refreshing life-force in what is between the here and there.

Cowan’s work opens and constructs admittance to passages that are between the then of the background and the now where the viewer views. Light, air cannot be confined, escapes to forfeit explicit definition. She squarely frames the mounted cut paper sheaths, veils of secret containment. Mysteriously, they are entirely open, candid, without artifice. The square format unifies, protects furtively. Her installation is rhythmic in their even, equalising installation.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

c.1200, literally "wind eye," from Old Norse vindauga, from vindr "wind" + auga "eye". Replaced Old English eagþyrl, literally "eye-hole," and eagduru, literally "eye-door."

Works, individually and collectively or in any pairing becomes ‘eye-doors’, openings into Cowan’s verb activated perceptions. Winding, over and around, through each lacy curvature that never tangles, each means of access and observation allows us the means to pay attention to sensation. Cowan’s verbs apply to each piece or some or all. flow: Like a pale blood stream or an electromagnetic course, the use of flow issues a graceful continuity of line that moves steadily and easily. sway: Cowan persuades through movement, influences throughout the vacillating performance of line shaping form, form shaping seminal lines. Decisive and significant scores oscillate to determine change through credible stillness, a quiet assertion. wave: Beckoning, wave is a flourish of line that gestures towards and away, an oscillating command. swing: Suspension, triggers that dangle and play, swerve and return, each line to the other and back, swing oscillates.sweep: Carrying curve upon curve, the arcs rush, grab and seize the viewer in oscillating passes. ripple: Undulation swelling, a heaving softly, cut to preserver, sustain the denotation, ripple is oscillating encapsulated.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

Shadows are strong and oscillate, changing shape as the viewer passes. Agile curves reflect overhead light and combine with the colour of the background washes, emphasizing the shadows’ explicit and transient vacillation, the quintessence of enunciating movement between indecision and resolve. The works pronounce shadow, affirm the cut lines and weave together as essential players. Shadows are subjective, the result of reflection. Each work in this series are segments of humanity contained, enlarged and presented as lively entities for our benefit.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

Cowan’s verb association clarifies the function and appearance of each individual component or work, and the groups or configurations of the panels or the whole set of panels as window envelopes. She displays the means of access or observation and ways for tangents to form, ways to engage with the work through her verb associations. The works are intervals of time during which the verbs can or must activate, windows of opportunity. The works confuse, mystify, hearten in their elegance made from uncompromising cutting. Each square conveys frequencies of magnetically charged atmospheres. We experience windows into ranges of ethereal landscapes. She produces conductivity and we, through her subdued inspired tones, and stark shadows resulting from the undulating shapes and their performance summons us to and through and around these cognisant, self-contained portholes. Each feels like an opening where one might access yearnings and potentially, launching the viewer one perpetuity.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Being’ / Human, all too human.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Being’ / Human, all too human - detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna

~ Shakespeare. Othello. ACT III SCENE IV

“Othello: That’s a fault.

That handkerchief

Did an Egyptian to my mother give;

She was a charmer, and could almost read

The thoughts of people: she told her, while

she kept it,

'Twould make her amiable and subdue my father

Entirely to her love, but if she lost it

Or made gift of it, my father's eye

Should hold her loathed and his spirits should hunt

After new fancies: she, dying, gave it me;

And bid me, when my fate would have me wive,

To give it her. I did so: and take heed on't;

Make it a darling like your precious eye;

To lose't or give't away were such perdition

As nothing else could match.

Desdemona: Is't possible?

Othello: 'Tis true: there's magic in the web of it…”

Handy squares of fabric through time, with a considerable gap from the 1930’s to the present when Kleenex advertised the use of their product as a means to prevent cross-contamination, handkerchiefs were the main runny nose and eye wipers. Morey has stitched pain into mid century hankies superimposed with swatches, parts of the work, letters of the word ‘trust’, without completing the word in any one of the works. Her patches like bandages covering lesions are stitched awkwardly, lugubrious and angry. Labours of embroidery stitches are sustained contemplation, not finished to any specific end, mere musings. Stitching threads mournfully trail beyond the squares. Downward and tangled threads show despondency at the attempts of neat resolve, tails/tales of woe.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Being’ / Human, all too human – detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna

Charming reclaimed heirlooms with captive designs, each with individualised decorative borders, some with prints and petite point treatments would have been amiable as the carrier duly dabbed watery eyes or weeping nose through amusement or sadness. These handkerchiefs would have been an attractive and enhancing pocket embellishment. They would have been a mode of transit as gifts to cultivate relationships, cherish the giving and the giver. They would have been sources of pride and the means to reinforce what might otherwise be unspeakable. Someone would have given care to wash and press, fold and store the carefully constructed handkerchiefs as reverence for the relationship and the article that would find its way to intimate acts of personal self care. These handkerchiefs were definite articles of being.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Being’ / Human, all too human – detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna

Shakespeare’s Othello’ handkerchief was the ploy for his loss of trust, his subsequent murder of his wife, Desdemona and his own suicide. That cloth swatch was powerful agency to the demise of their relationship, the death of its members. Misplaced trust like Desdemona’s misplaced handkerchief will threaten, injure and beguile. There is hanky trickery. Morey’s mesmerizing, incantations of desolation perform as ritual recitations, over and over each one a different aspect of the same anguish at the breaking of trust, or how trust broken has many hankies. These proofs of dejection and quail are nailed to the wall for guaranteed direct looks, or deferential looking way at the suffering through its delicacy of vulnerability of their wearers told by theses handkerchiefs.

Articles of being, Morey fashioned handkerchiefs with the aftermath, the meaning associated with tear stains. Suffering fault appears as dried discolouring blood tinges on white grounds, bright red thread as the continuous ooze of the outwardly imperceptible inner haemorrhaging from tearing where people once connected to each other. Scrunched, discoloured, blotted spillage, spoiled with wounds and wounding, through Morey’s scraps damage is concealed, reinforced, and cannot really repair puncture holes to the unsalable spirit. .Remnants haphazardly stitched on maligned squares she shows how human it is to be indefinitely affected by broken trust, bleed out sorrow. The handkerchiefs explain relations scarcely darned, holding on to imperfection. A letter here, letters there, Morey shows broken trust as patched up, redressed wounds. Numerous scenarios as separate hankies detail the divergent ways being human impacts the fabric of their disappointment. She shows how each breach of trust, each tender incident, regret is felt, is apparent in distinctive expressions on every square.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Being’ / Human, all too human – detail ~ photo by .Amber McGregor.

Trust suggests promise, a depth of feeling that is not assured in its degree or extent of its reciprocation. Unlike faith, a belief in positive outcomes or conviction which is evidence based confidence, trust is reliant on hope. Morey’s the subtitle is also the first part of a book by Friedrich Nietzsche called ‘Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits’ (1880). Part 1 in the chapter called, ‘History of Moral Feelings’, section 71 refers to hope as ‘the greatest of evils for it lengthens the ordeal of man.’ Nietzsche was writing about hope, the only remaining evil left when Pandora’s box of evils was opened and escaped.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Being’ / Human, all too human – detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

Handkerchiefs, the crafted tidier of emotions are redemptive, offering hope and healing. Morey mediates this hope, hanging pain, with all its mutilating ignominy and raw aches, the awkward, delicate and complicated affects of eroded trust for all to see like war-worn prayer flags. Trust starts as an idea that is comprised of innocence, a confidence in incorruptible virtue. With the best intentions, an oscillation between purity and lapses of candour will alter commitment and responsibility. Trust’s weight, its ability to absorb and consign significance to each participant in relationships can be a teeter-totter between expectation and ultimate result. Some consequences of human fallibility include broken trust and its reparations. These complex qualities are some of the foibles that make us human. Morey’s work exemplifies precipice, the danger of assailable vulnerability displayed as banners to negotiated truce with the fear and lure of human interchange verified – enduring mythical hope as mends. A source of damage to relationships is also hope, as terrifying as an evil spirit and can be a preeminent quality of humanity, an oscillating conundrum.

Morey: “I like the tension between what is beautiful and tragic at the same time – beauty on the edge of terror. When we push ourselves to the limit – that’s kind of where we end up negotiating those two things together.”

Connie Michele Morey : ‘Fingertip Cartographies’ / As we name they planets, they dance.

‘Life is a wave, which in no two consecutive moments of its existence is composed of the same particles.’

~ John Tyndall. In 'Vitality', Scientific Use of the Imagination and Other Essays (1872), 62.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘Fingertip Cartographies’ / As we name they planets, they dance ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey.

Morey has populated an entire wall with grape sized, hand formed felt pellets, brilliantly coloured solid perfect orbs impaled with long pins, some with wool tendrils escaping, discharged, projecting, wavering in multiple directions. The constructs are sometimes singular, often in groups or congregations. Grapevines of information, assemblies of the fixed felt ball bodies with and without wispy strands cast strong shadows that intermingle with each cluster, beyond each faction, sometimes in pairs, sometimes crowded and interacting, sometimes solitary, fusing one with the other or deflecting and distinguishing the colour spheres on their pinions with and without the gesticulating tresses. The shadows are lively, complimenting the source of the manifested spectres.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘Fingertip Cartographies’ / As we name they planets, they dance - installation ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey

Connie Michele Morey: ‘Fingertip Cartographies’ / As we name they planets, they dance ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

There is no reliable plot, no extant plan or proven chart, no precise map or definitive diagram about how to exist or the process of existing instantly available at our fingertips, ready for plucking. Like Morey’s populated wall people relate to each other with fuzzy brightness and intertwining tendrils on pins of anticipation and resolute commitment. They, negotiate, mediate, cooperate through periodic events, recurrent actions, cycles of impulses, conduction and constrictions of daily living. We exude electromagnetic cycles of feeling that waver and interweave. Multitudes of beings extenuate from their vertex, the best of themselves, tip toe reaches, stretchy finger extensions shooting for something, anything that may miss, may connect to a beat, a pulse, a way to unite and bond. Shoots and thrust of emotional strands crave throbbing or ripe hearts as felted perfections that straggle with their pin retainers. There are cycles of conscious and indiscernible expansion and times of luscious and salacious compression. Warmth, demonstrative development as hot colour is relational to its loss, the miscalculation. Some wisps wave in lonely space. Morey’s entities exist in waves of oscillation where movement and slowness, stillness of being coexist. Her dancing time particles designate oscillating cycles as improvised boogies of ontological dimensionality.

Morey explains the expanse of ontological interrelations through her microcosmic / macrocosmic work. By pushing in the pins into multiple miniature felt orbs, she provides a buffer between the infinite plane and points to the place, the necessitated places the pin with ball into the wall dwell together. This work is a luminous moving expanse, a cacophonic harmony of arbitrary exactitude. Tiny colourful points of existence and reflection, redirection are pierced, held fast, like bugs on an entomologist’s board for further investigation or planetary bodies named by feelings that colour emits or holds.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘Fingertip Cartographies’ / As we name they planets, they dance ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

She allows a creepy-crawly feeling, those wiggly bits, the pins sticking into softness in her exploratory discourse as the means of investigating the uncomfortable, unexplainable in life. Morey’s wall is an exposé of action and influence through charm and uncanny oscillating depths of elegant gleans of significance contrast perceptible deliberations, how yearning with burgeoning awareness entails introspection and assessment, rejection and collaboration. She disseminates the assiduous expanse of understanding as near pinprick and distant inexplicable comprehensiveness that wind or wish might alight upon. Her contrivance to demonstrate the unexplainable presence within relations is a both juggle and jostle, much like competition and regeneration. Morey creates points of scrutiny, sharp punctuation, alarmingly bright centres of strength and integrity with nebulous, tenuous calls for something more. Morey’s work is a wall of existence.

‘People travel to wonder at the height of mountains, at the huge waves of the sea, at the long courses of rivers, at the vast compass of the ocean, at the circular motion of the stars; and they pass by themselves without wondering.’

~ From:Confessions of St Augustine (c. 397). Book X

Saint Augustine of Hippo

' Oscillatio' - installation ~ photo by Sarah Cowan

Sarah Cowan / Connie Michele Morey - 'Oscillatio' installation ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey

Sarah Cowan and Connie Michele Morey together and separately journey beyond secure stability, allowing uncertainty to bring us wonder. Interstices of oscillating thought amplify and burst forth as conviction. Together they penetrate qualities of fluidity, ascertaining the durable, complex resources to sustain and thrive. They both dance heartening rhythms. Drumming the pulsations of imperturbable queries, they complement each others’ oeuvre and distinguish their individual practices. Oscillatio moves, absorb our collective consciousness, abounding in connectivity. All the works, like permeable membranes, process ideas that allow us to feel acknowledged, steady us and remind us of trickiness in our collective chaotic, shadowy dances to resplendence we oscillate within.

Sarah Cowan and Connie Michele Morey

xchanges gallery

2333 Government Street, Suite 6E

Victoria BC Canada V8T4P4

9 – 25 January 2015

Review by Debora Alanna

Exhibit-v video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ROHNz8pHLjc

‘Our thinking tends to circle around established conventions whose basis is forgotten or obscure. Nietzsche proposed that the attainment of knowledge requires a ‘solid, granite foundation of ignorance’ for its unfolding: ‘the will to knowledge on the foundation of a far more powerful will: the will to ignorance, to the uncertain, to the untrue! Not as its opposite, but – as its refinement!’’

~ 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl, Daniel Pinchbeck, 2006, Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, New York, pg. 3

Oscillatio is the xChanges exhibition of work by Sarah Cowan and Connie Michele Morey. Together and individually they deliberate and establish truths that exist through paradoxical and simultaneous ideas. Each utilizes the sensibility of commonplace materials inherent in crafting. By using humble, naive media, both artists establish and work from this foundation to promote unfolding ignorance (see Pinchbeck on Nietzsche, above) and refines the unknown, willing the minute of substantial truths to exhibit within Oscillatio. Both artists have deep and profound knowledge of the human condition, but are willing to exemplify the adage, the more you know the less you know, a philosophical discourse found in agnoiology, the study of culturally based ignorance or doubt. Allowing themselves to work with modest materials, they begin to counter certainty with the oscillating stance of the ignorant/informed shifting on the precipice of the unknown and known.

Their materials and use are laden with emotional contexts because of the original intent of the materials used as a means of caring more, better although with the utilitarian outcomes crafts are crafted for, made to withstand, bolster goodness in harsh and impersonal realities. Cowan and Morey’s practices address basic material use through subjugation and ingenuity.

Cowan liberates paper with expert mastery, establishing a physical connection to her medium. Then, from the original flat beginnings she adeptly expounds frisson, embodiment of intense shudders through her absorption and incisive perception. Her rigour and deference to the limitations of paper are countered by Cowan’s testing and taxing of herself. The memory of this arduous process seems to vibrate within the work and becomes a channel for exuberance.

Morey challenges wool, fabric, notions, handmade toys and more from its original confines of homespun intent. Works nurture rifts unapologetically but offer accord at the same time. They coax nostalgia that triggers tension between approval and disapproval one might find in argumentative conflicts. She stretches the intent and physical limits of her media, her means to concurrently investigate universal discourse.

Their investigations are the veracity of thesis and antithesis, honouring differences and similarities, not with the objective of sanction or an opposing stance. Each artist allows their esteem for their fundamental, modest materials to be challenged and confirmed. A substantial range of exploration heightens the experience of coexisting works. Together they inform and enlighten the viewer about the wide spectrum of familiarity, ritual, play and work practices. Oscillatio is an interrogatory intervention where the oscillation process humans flout, breach, elicit and present are shared by being alive, given the credence of uncertainty.

Throughout Oscillatio, circles abound. Works engage, encircling the oscillating ideas that define existence. Groups of work define explicit processes that are sensed, felt, cannot be easily named. Spheres of influence, interest and personal though individual, parallel or contrary are persistent with shared domains that thrive in the honest pursuits of each artist. They reveal and disclose lives lived, the living being an encircling oscillation as a means to impart realms of exhilarating verve. Cowan and Morey allow an individualised introspective discourse and a unifying perspective on versions of the flux we sense, encounter, impart and epitomize throughout our lives.

‘In The Arcades Project, to cite is at once to explode and to salvage: to extract the historical object by blasting it from the reified, homogenous continuum of pragmatic historiography, and to call to life some part of what has been by integrating it into the newly established context of the collection, transfiguring and actualizing the object in the “force field” – the oscillating standstill (Stillstand) – of a dialectical image. The redemption of the past in constellation with the now, adumbrating in language a “nucleus of time lying hidden within the knower and the known alike” (The Arcades Project, N3,2), takes place in what Benjamin will call, in his 1929 essay “On the Image of Proust,” “intertwined time”. This is the temporality of montage.’

~ Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life, Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA., 2014, pg. 290-1

Cowan and Morey, each in their independent practice and through a year of collaborative thinking have produced work that ruptures the homogenous continuum of pragmatic research or practical consequences. Osscillato is a collective of ontological studies where the oscillating standstill of each work (see the Benjamin description above) involves a tension of conflicting ideas, taut opposition that focuses on the sustained relational commonality between the artists, what knits humanity over time and what can be discovered in Oscillatio’s tableaus.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Knowing’ / As logic weeps.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Knowing’ / As logic weeps - photo by Debora Alanna.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Knowing’ / As logic weeps ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

In the centre of the gallery, Morey has set a table with Paddleball / Bingo-Bango shaped distressed bats set in 2 arrays. Each paddle sports felted balls where rubber balls originate in the children’s apparatus’. Words of comfort are stitched with large patches, considerable sutures to the nebulous, misshapen wool orbs fixed with elasticised extensions to the paddles.

Attendees are encouraged to play, hit a woolly subject against a thinning pink, sand paper afflicted flat rounded blade. Paddling Morey’s paddleball is an unwieldy and rarely successful action because of the weight and ungainly shape of the grey woolly balls with added disproportion of thick patches and heavy stitches do not correspond well with the intended hitting surface. The entire exercise is wonky. And can be fun depending on why one engages in the challenge of this endeavour. Morey educates us through our play.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Knowing’ / As logic weeps. ~ photo by Amber MacGregor.

The balls become fuzzy, the elastics tangle. Oscillating movement of the boinging between woollen mass and stretchy flex in opposition to the propelling force of the player and the bat, a hostile though seemingly playful intent diminishes the idealised mean, the havens of existence named on the balls. The action targets the best destinations of refuge, wearing the spheres of sanctuary. Our ultimate needs become worn even with the best intentions and light-hearted engagement. Our logical selves suffer when we know what is between ourselves and others – the unexplainable outpouring of something, the bounce, the banter, the intertwining. When we know we have been the instrument of change, the knowing becomes the condition for our consternation and joy. Each elasticised bat conference is a reason for tears of laughter or lament, an emotional confusion. Leaving the game unattended without play, we learn nothing.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Knowing’ / As logic weeps. ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey

Connie Michele Morey - 'Oscillatio' installation of ‘On Knowing’ / As logic weeps(forground) & ‘Fingertip Cartographies’ /

As we name they planets, they dance (rear wall) ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey.

Sarah Cowan: ‘Untitled’ – installation.

Sarah Cowan: ‘Untitled’ - installation ~ photo by Sarah Cowan.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' - detail ~ photo by Sarah Cowan.

Cowan’s largest work is untitled but associated with Emily Dickinson’s second verse of the poem, ‘Of Being is a Bird’, with a slight change to the second last word – than instead ofthe:

It soars—and shifts—and whirls—

And measures with the Clouds

In easy—even—dazzling pace—

No different than Birds

Cowan’s work does soar, shift and whirl. Although she has with a measured, deliberate pace calculated the temper and extent of each segment of her four part work, she takes us aloft to realms of enigmatic mysteries clouded by our utilitarian lives. Through her inscrutable even pace, her serious fancy she has produced a spectacle dazzling in our presence, ferociously wild, intricate passages – no different than birds’ pace.

Sarah Cowan liberates large pristine sheets of white paper (3 x 8’ aprox.) from a static continuum. Beginning as a dance, a celebration of delight with spherical movements conjoined over the sheets, she widens her space, stretching her being to allow her pencil to clearly demarcate ubiquitous connectivity.

Sarah Cowan: ‘As I was making these, I kept thinking of myself as a young child. There were times in my life when I was absolutely exuberant, full of light, all bubbly (…) Maybe that is the child in me.”

She works with youthful certainty, allowing the definition of space to begin, extend from her dexterous manipulation of the flat plane through her sphere-shaped drawing. She defines circuitous living, lives lived intertwined, how they bond, how they curl and circle toward, away, together and apart. Cowan shows how life is a continuous dance, a comforting encircling togetherness yet with estrangement that is shown by each unique circling curve drawn. Cowan’s paper is embodied as clustered protuberances, interlaced auras evoking Cy Twombly’s scribbled knots but without his pathos. Cowan emanates airy elation bursting forth as a quatrain or quartet, four sustained intentions that ultimately work together as body language.

Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is…

~ from Four Quartets: Burnt Norton (1935) by T.S. Eliot.

Her circular advance and development is comprised of unique transfers of feelings, passages between changes and challenges to thought without verbal articulation of reflection. Lines became Cowan’s scheme to articulate power and strength, consternation and resolve through the adversity of the rhythm of stir to stop and start, breathing’s tautness and release all finding their integrity through her pulsating pencil. Lines show tenderness, vulnerability. Succession of round marks pursue cycles and transitions from one point to another, the lines between encounters, touch and retreat, endurance through the ache or niggle. Her fun in raising the drawing implement to the next point of ingress beginning anew, transformed her page with each line inscribed with roving intent.

Cowan’s work required immense stamina. Each work, its elements reiterate, amplify her ideas about the constituted fortitude in the oscillation experience. Cowan established how and what matters with her unremitting flow, fly over the page. She appointed marks, drew incisively, precision being the significant consequence of incessant, substantial strokes. Contours underscore urgency. Connectivity related the paths of bonds and networks, relational charges, the apprehension and relief of correlation. The unshakable flourish of Cowan’s pas seul, her intense circumnavigation of bubbling bursts, connecting corpuscles, cellular awakening throughout her boiling effervescent choreographed overlay becomes our focus that allowed the next stage of her work to find its own vigorous voice.

The next stage of Cowan’s intrigue began with an Exact-o knife cutting into the outpouring of marks. The outstretched paper rolled into a scroll of paper showed the current of lines of integrity, reliable shimmy and glissade, the stream of incised exactitude and meticulous austerity of movement. Removal of the centres of the curves left tantalizing, slender contours in the paper drape leading to her foursome of uninterrupted, protracted incantations. Cowan summoned the means to living with and without the breach of fissure and mend. She lures the timelessness of an ample and wondrous existence. Cowan worked through the trepidation entrenched in mistakes, utilizing the practical composure of belief in her oscillating configuration to attain the best one can be because of the conviction and engagement in a labour of love.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' – detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

Time, that oscillation between here and now, the instigation, activation – what was then and is future, the product and its consequence, the next step, the time between commencement and working within the core of the idea, its manifestation, its medium, the intermediary stages, the progression, the route, the handling and the manoeuvres through to the result – all these phases and junctures are inviolate, common to everyone as stages in living. Time demands and constraints are eloquently embodied in her work. Time management compels Cowan. Drawing her into a strict timeline with scrupulous care she translated this absorption as obdurate dedication. She shows us how to stay accommodating to the means of obtaining a meditative life while being intractable to our goals and especially, the outcome of perseverance through adversity. Cowan’s lessons are gleaned through her drawing practice, cutting dozens of paper circles from a sizable paper sheet. She transformed these humble acts into gossamer filament. Cowan’s sharp keen incisions becomes transcendent the way understanding lies beyond the scope of observation and insight. These works are independent of their materiality.

The final stage of her work required, expounds subtlety and diplomacy. To hang each work on the wall, adds sensitivity to the liveliness of the splendid, intrepidly cut sheets; she found the edge of the middle top point to acknowledge the splendour and modesty of its integrity. Her paper is animate. It glows and bustles. It breathes with every wisp of activity in the room. The four entities suspended, suspending abeyance, defer commotion and disbelief in the existence of animate spirit through her paper cut outs. The works hang upwards. This work holds and ensnares us simultaneously in awe and uneasiness at the interface.

Cowan encourages trust, conviction in possibility of the power of the unseen. Energising with their glow, these sustained tacit expansive notations became affable and congratulatory in their grouping. Perky, they oscillate between generous leeway of understated options and risk in confidence that might tear or be shorn by inadvertent contact that could defile the intact units. They generate concern about close contact, the way humans have anxiety about touch, not knowing, the uncertainty of limits, boundaries between people. The works show how we oscillate between perception and significant intention, meaning. These entities combine forces to assert the quietude explicit in regal stance.

The four cut-outs exemplify the invisible network of neurons and electric impulses that constitute our essence and emulate from our being with that unseen though omnipresent iridescence. Cowan reveals the foreboding we fear and love, the juxtaposition of the forbidden and divine within our natures. Her cut circles, all a-jumble when hung, retain their repeated movements, superimposing each other in an allied constituent of light and shadow. Converging and diverging colours of shadows and movement meet, touch, jostle and transition, lazing cloud-like formations modify with each flutter of a passing viewer, the gust from doors opening and shutting the way we quiver and flex as people pass us.

Sarah Cowan: ‘Untitled’ – detail. ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey.

She produces a liberation where circular drawings are scribed by a knife into thinnest lines holding each other together as an elusive unit. Cowan mediated the standard of intent. Her care, scrupulous scores devise an oscillating dance of shapes when the cut sheets are hung. Bodies of provocation vibrate and undulate as individual essences and as a collective association.

Cowan defines our characteristics in her suspended verses as the oscillating compunction of anticipation and expectation, willing to participate, waiting to be involved, needing interaction to be moved. She shows us to be individual. Each of her works are fundamentally unique in their execution, implementation and affect. Like humans as a group, they are the same make up, same arrangement and shuffle of nerves in circuits. Cowan’s sculpture bodies share their space and are fostered by their association to the others in their corps of lively dancers. She has cut through brisk vacillation and buoyant swing moves to advance a conglomerate of contour, an oscillating dance.

Sarah Cowan: ‘Untitled’ – detail. ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey.

Cowan’s oscillating forms are brilliant colour cacophony where no query is shadowy. She is specific about each line as interrogate of space, place and time, past and present in contrast and in unison. Shadows from these lines of enquiry become assurance, bolstering the challenges she poses of threadlike demarcation, sheer tenacity becoming the stringency of diaphanous light against blush and flush, shades of oscillation as intricate ripples, recurrence within absorbing circulatory machination.

‘In/Significance’

Hugo, tell me, dare I speak of love?

Connie Michele Morey: ‘In/Significance’ / Hugo, tell me, dare I speak of love? ~ photo by Debora Alanna

To the left of the corner, a little above eye level a woolly sheep’s backside is attached to the wall. To the right, a board spells ‘devour’ in the top half of the work. A black and white print of a nursery lamb image is collaged to a rectangular board rising slightly above the word’s picture plane. Small colourful felt balls punctuate the surface of the smaller board and seem to emit from, and/or be filling the mouth of the lamb, surround the lamb, floating about. The work is based on an encounter with a child that is known to the artist, their relationship through his growing maturity. Innocence devours, is allowed to assimilate, consume as much as they please of grace, gentle frequency and colourfast quality of love given. The giving needs to be as light as floating coloured particles, as diverse, as multifold. The giving of love and especially the telling must be a suspended act, or very particular, wily. Feeling without any imposed intention can be lightly, softly released. Otherwise, the lamb/ child could choke. Proclaiming or explaining the act of conferring love is suspect. Identify love, mention the giving? Ask if one may speak the depths souls seek? The answer is no because the lamb / child is an insubstantial cut out image as a result of that question, if posed. This question is for an idealised lambkin.

Morey shows the lamb as a black and white illustration in converse with the floating coloured balls because the idea of lamb/ child is not the child. The love/balls is/are tangible. The lamb in the picture cannot ‘speak’ for all the love surrounding it - being eaten by the lamb, devouring the lamb. The outcome of questioning if love can be spoken of is shown in the side sheep facing up, diminished, against the wall, sequestered. It is not in the main picture plane.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘In/Significance’ / Hugo, tell me, dare I speak of love? – Installation. ~ photo by Amber MacGregor

Questioning is significant and ‘In’ (conspicuous) because the sheep’s back is turned to the main, conscious of the ‘Significance’ of the naming - of the exchange, Morey makes a comical tantrum because naming, telling is desirable for the adult. The backward sheep, like adults, are aware that the amount of love given can be overpowering, becoming almost “sheepish” however much desired.

The mainstay portrait is disassociated with the cornered sheep, allowing the abundant love balls to drift, hover and soar because finally, the love giver knows better than to impede its love with prattle.

‘Cling taxon, Cling’ / A fixed point of view spins injustice. ~ Connie Michele Morey

Connie Michele Morey:‘Cling taxon, Cling’ / A fixed point of view spins injustice. ~ photo by Debora Alanna

Morey’s trio of wooden carts each set on its own cantilevering shelf filled with plastic balls, a coloured nipple atop each is accompanied by an invitation to ‘participate with the work’. It seems a nurturing requirement. The balls can be thought of as a collection of eyes, too, in wandering directions, none seeing the same direction or point of view. They can be the regulated opening for discharging, intake of thought, feelings, the nebs of the collected group of itinerant souls. They are the collective consciousness unconscious in their stand still.

Connie Michele Morey:‘Cling taxon, Cling’ / A fixed point of view spins injustice ~ detail. ~ photo by Debora Alanna

‘Taxon’ is an animal or plant group having natural relations. Compartmentalisation ruins what is worthy, cultivates immorality and implies injustice. Taxon is a natural grouping where changes occur to adapt and improve the longevity of the species. Taxons cling to their integrity. Morey encourages this hold that will prevent categorising; a violation of impartiality because bias is without integrity. Each taxon has veracity and evolves, too. Change can be upheaval for a species. This motion and stirring disorder is ongoing. Sometimes requiring an outward impetus to develop, the balls’ commotion seems at a standstill.

Connie Michele Morey:‘Cling taxon, Cling’ / A fixed point of view spins injustice. ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey.

The equal sized sameness of the balls are relations. The contents are relational, be it side by side, apart, together. The three four wheeled carts are a group, relational in their size, colour, material and accommodation. All carts have strings. All have balls as the end of their pull. One of the ball entities is waiting, in askance for the job of motivating, moving the cart, and it has no colour to define itself. The balls inside the draw correspond in their size, with coloured tips, although each of different colours all have the same dimension, substance, height. Each cart has a similar shelf but the shelves are in slightly different positions, varying access according to arm stretches available to reach. ‘Cling’, in Morey’s title consigns direction, as we must cling to the pull to move the cart, cling, as the shelf clings to the wall, cling as we might be happy the balls are contained and will not roll away when we pull the cart, clinging to their containment. Moving, the balls jostle against each other, rolling hither thither but do not cling except as an autonomous group of containment and, in that case, spin, may touch in the unison of transport. Unattended, without consequence they wait for interaction. Fixed views, although the interaction may change their view, intermingle to further alter views from the positions they held on the shelves. Retaining the same viewpoints would be very difficult because of the nature of their spherical bodies in motion and eventual rest, just so.

Justice necessitates a moral and political philosophy discussion. Morey offers a succinct triad of fixed viewpoints that translates the big subjects for us. We oscillate between justice and injustice because they are scary and difficult concepts. Often, we would in our daily rituals rather leave philosophy and politics for philosophers and the politicians. But we need to pull the cart by the balls, allow the balls of complacency to roll around to achieve discourse. Morey’s work entreats we craft our thoughts and actions to allow the roots of our thinking to be foundations for effective, just living. Not an easy plaything, justice.

The works on shelves are nearly the same unless the sculptures are contacted, played with allowing imaginative associations and a rapport to form, dialogue. Engaging with the carts allows meaningfulness to develop, memories to be made, nostalgia for the object in association with a pleasurable or frustrating or confusing or illuminating time spent with the plaything, carrier of eying balls detached from humanity’s taxon, Homo sapiens (Latin: wise man) - wise assessment and action is requisite to our grasp.

Morey’s work, her call for interaction can be understood as oscillating metaphors for the idée fixe and its horrifying outcome if we remain uninvolved. The sameness, the fixing of certainty without question, without doubt, without interplay is about the shelving of sincerity, the stagnation of perspectives. Passionate, unquestioned belief systems may result in amorality, vice or otherwise diminished character. Minimized individuality or individuals welcomed, groups clinging for any reason or emotional need or forming, reforming with the best intentions, including socio-economic groups will determine the flexibility or inflexibility of thought and deeds.

The quality of justice within society might become objectionable, detrimental to individuals, groups or the whole of humanity and may be defined by fixed viewpoints. Immovability will apply to the ethics of social decision-making, the doubtful categorising that people cling to in the absence of change or if no interaction occurs. Understanding is oppressed if viewpoints are shelved. Taking Morey’s carts out for a spin demonstrates the initiative required to take ideology off the shelf.

Sarah Cowan: ‘Untitled.’

flow

sway

wave

swing

sweep

ripple

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' ~ photo by Connie Michele Morey.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

Through 1967-1968, Richard Serra wrote a list of verbs ("Verb List" was published in 1972 in the book The New Avant-Garde: Issues for the Art of the Seventies) to act on, divulge and include his material process beginning with industrial stores in his studio. He devised the list to act on manufacturing materials considered non-traditional at that time. He wanted to experience the materials in unconventional ways. He wanted to counter Donald Judd’s ‘Specific Objects’, the consideration of sculpture as nouns and suppression of process. Verbs are words that show an action is happening, that a state of existence is taking place or condition, mode of being is occurring. The word is about the present, our acts, our status qualified.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

Cowan has named states, designations through verbs for us to think about in a framed wall mounted series. She listed verbs to associate with each of the 8 x 8” cradles painted various tints of light blue overlaid with one or two cut paper layers forming apertures, interfaces between her sensibilities and our experience of her work.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

These words read like a list of verbs from Serra’s list. Serra’s intent for each verb is implicit as she pairs the verbs with an infinitive ‘to’, which indicates the verb is independent in existence or function, having no overt subject. Cowan has omitted the infinitive because her words are more inclusive, allowing the work to describe meaning beyond the verb. Her verbs accentuate the work, give the viewer assurance, helping to fathom Cowan’s pieces. Like Serra’s use of verbs to act on the action – the focus is the action – Cowan’s verbs informed her work practice through evocation the verbs provided, although she is the subject, and we see her view of the world looking into the piece, or her viewpoint looking out, an oscillating perspective.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

Each work of this series has a sympathetic vibration, an oscillating resonance within and between each of the squares. The minute apertures are relatively small in comparison with the larger four works in the main gallery space. There is a personal space articulated within these works, an intimacy, a privileged discourse. The pulsating of the works seems more intense than the frequency of vibration of the larger works, a kind of incidence that reverberates although of her cut paper overlays on the diminutive views are slightly thicker with more substance. Each of these works has a friendliness, an alliance, one to the other and a depth of vision afforded by the coloured ground against the paper cutting. Perspectives of the imagery changes as viewers move across and back through the enclosed thresholds. The works offer a current of alternating, subsiding oscillation between fluctuations of attenuation and density. Light produces a scroll to read and get lost within the changing window view, affirming refreshing life-force in what is between the here and there.

Cowan’s work opens and constructs admittance to passages that are between the then of the background and the now where the viewer views. Light, air cannot be confined, escapes to forfeit explicit definition. She squarely frames the mounted cut paper sheaths, veils of secret containment. Mysteriously, they are entirely open, candid, without artifice. The square format unifies, protects furtively. Her installation is rhythmic in their even, equalising installation.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

c.1200, literally "wind eye," from Old Norse vindauga, from vindr "wind" + auga "eye". Replaced Old English eagþyrl, literally "eye-hole," and eagduru, literally "eye-door."

Works, individually and collectively or in any pairing becomes ‘eye-doors’, openings into Cowan’s verb activated perceptions. Winding, over and around, through each lacy curvature that never tangles, each means of access and observation allows us the means to pay attention to sensation. Cowan’s verbs apply to each piece or some or all. flow: Like a pale blood stream or an electromagnetic course, the use of flow issues a graceful continuity of line that moves steadily and easily. sway: Cowan persuades through movement, influences throughout the vacillating performance of line shaping form, form shaping seminal lines. Decisive and significant scores oscillate to determine change through credible stillness, a quiet assertion. wave: Beckoning, wave is a flourish of line that gestures towards and away, an oscillating command. swing: Suspension, triggers that dangle and play, swerve and return, each line to the other and back, swing oscillates.sweep: Carrying curve upon curve, the arcs rush, grab and seize the viewer in oscillating passes. ripple: Undulation swelling, a heaving softly, cut to preserver, sustain the denotation, ripple is oscillating encapsulated.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

Shadows are strong and oscillate, changing shape as the viewer passes. Agile curves reflect overhead light and combine with the colour of the background washes, emphasizing the shadows’ explicit and transient vacillation, the quintessence of enunciating movement between indecision and resolve. The works pronounce shadow, affirm the cut lines and weave together as essential players. Shadows are subjective, the result of reflection. Each work in this series are segments of humanity contained, enlarged and presented as lively entities for our benefit.

Sarah Cowan: 'Untitled' detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna.

Cowan’s verb association clarifies the function and appearance of each individual component or work, and the groups or configurations of the panels or the whole set of panels as window envelopes. She displays the means of access or observation and ways for tangents to form, ways to engage with the work through her verb associations. The works are intervals of time during which the verbs can or must activate, windows of opportunity. The works confuse, mystify, hearten in their elegance made from uncompromising cutting. Each square conveys frequencies of magnetically charged atmospheres. We experience windows into ranges of ethereal landscapes. She produces conductivity and we, through her subdued inspired tones, and stark shadows resulting from the undulating shapes and their performance summons us to and through and around these cognisant, self-contained portholes. Each feels like an opening where one might access yearnings and potentially, launching the viewer one perpetuity.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Being’ / Human, all too human.

Connie Michele Morey: ‘On Being’ / Human, all too human - detail ~ photo by Debora Alanna

~ Shakespeare. Othello. ACT III SCENE IV

“Othello: That’s a fault.

That handkerchief

Did an Egyptian to my mother give;